Ain't Nothing Like the Real Thing

Tourism as the Commercial for City Living

Every year around the holiday season, New York’s Bryant Park is overtaken by a Winter Village, brought to you by Bank of America—now offering 0.01% interest rates on new Advantage Savings accounts! Like the bank, this tourist trap offers near zero interest to actual New Yorkers, but the tourists seem to love it. After TikTokking the Rockefeller Center Christmas tree and Instagramming the whimsical window displays of Fifth Avenue, the huddled masses descend on the Winter Village to partake of its holiday shops, faceplant on its ice-skating rink, and sip cups of hot cocoa in its Cozy Igloos (reservation required).

When we last lived in New York in 2021, and against our better judgment, we escorted some out-of-town guests there. Squeezed amidst the masses whilst we waited, as New Yorkers say, on line for coffees, I overheard-in-New-York a woman scoffing to her friend:

“How does anyone live here?”

While there’s a certain Yogi Berra aspect to her question—nobody goes there anymore, it’s too crowded!—there’s a grain of truth: nobody does live there. The Winter Village is meant to lure in tourists, and it’s the type of attraction that New York does especially well. The backdrop scenery of the city’s skyscrapers and the stage of the park itself imbue the Winter Village, a production that otherwise has nothing to do with New York in particular, with New York’s particular character. It gives visitors a sense of experiencing the city…without actually having to experience the city.

What that woman saw was the ugly sweater version of the park—and concluded from her experience that that is what New York life is like.

But Bryant Park is one of those great urban amenities that makes the actual experience of life in the city not just bearable, but wonderful. So from the local perspective, the transformation of a beloved amenity into something specifically manufactured for visitors is an alienating experience. While the Winter Village Occupies New York, no New Yorkers go there, not because of the crowd, but because its essential New York-ness has been crowded out.

This is the familiar tension between locals and tourists, ground that City of Yes has covered previously in “Who Are Cities For?” While that essay focused on the problems certain cities are facing with “overtourism,” the problem with tourism that most American cities are confronting is that many tourists have still not come back.

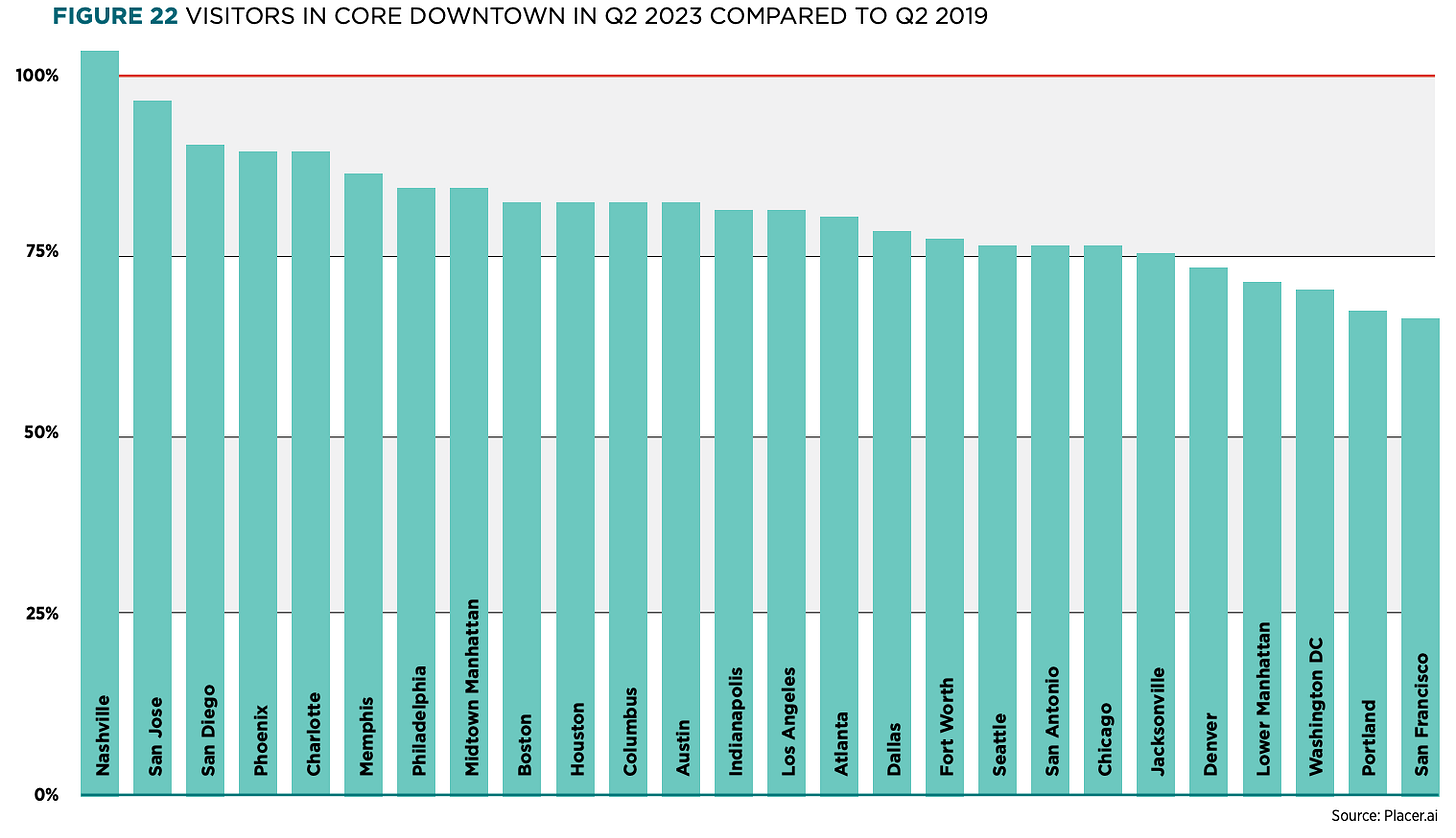

When we took our guests to the Winter Village, I was just happy that there were any tourists in New York at all. At that point, days before the entire city would seemingly catch the Omicron variant of Covid all at once, the return of visitors to hard-hit New York seemed to herald the beginning of post-pandemic recovery. It was premature. While New York is expecting to generate a record amount of tourist-related tax revenue this fiscal year, largely thanks to price inflation, the number of tourists is still deflated relative to 2019. Across the country, people are just not visiting cities at the same levels they used to. Indeed, almost no American city has recovered the foot traffic—of residents, workers, or visitors—that it had before the pandemic (but nice job, Nashville!).

Filling empty office buildings and bringing back ex-residents are harder challenges than throwing up a Potemkin Christmas village. But what if that village could help with the other problems?

Indeed, attracting more tourists could be how cities recover more residents.

I’ve been thinking about this since reading a totally unrelated essay by venture capitalist Andrew Chen. Commenting on cultural critic Ted Gioia’s provocative essay about “Dopamine Culture”—the idea that much of modern culture is built around a “distraction economy” of quick but addictive hits of fun—Chen suggests that these distractions might actually be an efficient way for all sorts of creators to find product-market fit. And if it is a good fit—if the consumer likes that song snippet, that film clip, that sample chapter, that freemium version of the app—then the alleged distraction could actually be the precursor to increasing engagement and a long-lasting relationship. As Chen writes,

It turns out that while Dopamine Culture grows, many times all the short form content and experiences are just the commercial for the real thing. [Emphasis added.]

This phrase has been ringing in my ears for weeks. Might tourism be the commercial for the real thing—that is, for real city life?

As an n=1 example, growing up in the Connecticut hinterland of New York City, I always sensed the Big Apple on our periphery—on the news, in commercials for businesses serving the “Tri-State Region,” in the commuter rail lines that ran from New Haven to the mysterious metropolis beyond the suburbs. Whenever we piled into the car for family vacations headed south, the sight of those spires cresting the horizon conjured nascent urbanist dreams. But it wasn’t until we were returning home from one of those trips that my dad decided, on a whim, to detour into The City. We parked in a garage for the price of a small mortgage and then sauntered about Fifth Avenue for a couple hours before settling at a T.G.I. Fridays for dinner.

It was the kind of trip-to-the-big-city typical of suburbanites who didn’t know their way around. But for elementary-aged me, seeing the spires from the sidewalks, breathing in the smell of Central Park and its horse-drawn hansom cabs, feeling the press of humanity and the hum of all that energy—I knew then that I would live there someday.

Which takes me back to Bryant Park. When the city hasn’t transformed the park into a tourist-trappy Winter Village, it is oft-visited and much loved by New Yorkers, who repair to the shade of its London plane trees or repose in the sun on its Great Lawn. It’s a joy to experience without the ice skating rink and the shops and the Cozy Igloos—all the things that bring in the tourists and displace the locals. That’s a shame, because the tourists themselves might appreciate an opportunity, after experiencing the crush of Fifth Avenue, to catch their breath in a quieter space, with a hot cocoa from one of the nearby kiosks that serves people year-round.

If the medium is indeed the message, then the commercial that New York is showing to visitors during the holiday season is perhaps not the best advertisement for the real thing.

But maybe not? Tourist traps are often people’s first encounter with a new city, the things that first get them interested in going there at all. Without that spark, they might never get interested in the city beyond the Winter Village walls. Manhattan’s T.G.I. Fridays may have excited this kid from the suburbs, but it made me really curious to know how New Yorkers lived when they weren’t eating Loaded Potato Skins—it would be years before I realized, shockingly, that New Yorkers didn’t eat them at all.

On the day we visited the Winter Village, it was to show my then-six-year-old nephew the splendor of the city at Christmastime. It really is a thing to behold: the artistry of the window displays at Bergdorf's and Saks, the larger-than-life decorations strung across intersections and splashed across building facades, the city all aglow. But the magic ran out for us at the Winter Village, so we headed back home to our apartment on the West Side, where we lived our real lives.

The commercial is never the same as the real thing—and at least in New York, the real thing happens to be better. I don’t know what nascent dreams filled my nephew’s head, but I know he got a glimpse of real city life amidst all the glitz and glitter, and I hope instead of wondering, “How does anyone live here?”, he perhaps had a different question altogether—

How could anyone not?

In defense of the Winter Village, the restaurant kiosks there are way better than most options in the area and do a good job of highlighting the diversity of food in the city! As someone who works nearby, it’s nice to go there for lunch (or dinner haha) and it’s also been pretty good for finding Christmas presents from local vendors.

This article would have been so much better if you had added one more line: "And that's why we're moving back to NYC, mofos!" Or minus the mofos. Dealer's choice.