Cities of the Dead

Urban Planning for the Afterlife

Just a block north of my house lies one of Austin’s most exclusive gated communities. The city’s oldest families bought up the lots long ago, and homes typically stay within the family from generation to generation. Created in 1839, Oakwood has been home to governors, senators, freedmen who fought for the Union, and Confederate officers alike. Its 23,000 residents occupy just 40 acres—denser than Giza or Manila—and yet, despite all the people, it’s among the quietest neighborhoods in the city.

That’s because all my neighbors are dead.

Oakwood Cemetery has become part of the backdrop of life in my Central East Austin neighborhood. We walk by it daily with our dog—she’s not allowed inside—but sometimes I wander among the tombs, the glass monuments of downtown rising behind the stone ones. Laid out beyond the young capital’s edge, Oakwood now sits in the middle of it, bordered by homes, a Denny’s, a coffeeshop, a hotel, and the University of Texas sports complex. Had the city’s founders known their frontier capital would become a metropolis, they might not have placed the cemetery so close to downtown. As it stands, the cemetery is likely to remain a literal dead zone in the heart of the city for generations to come.

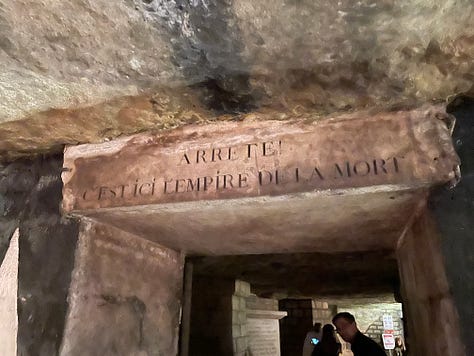

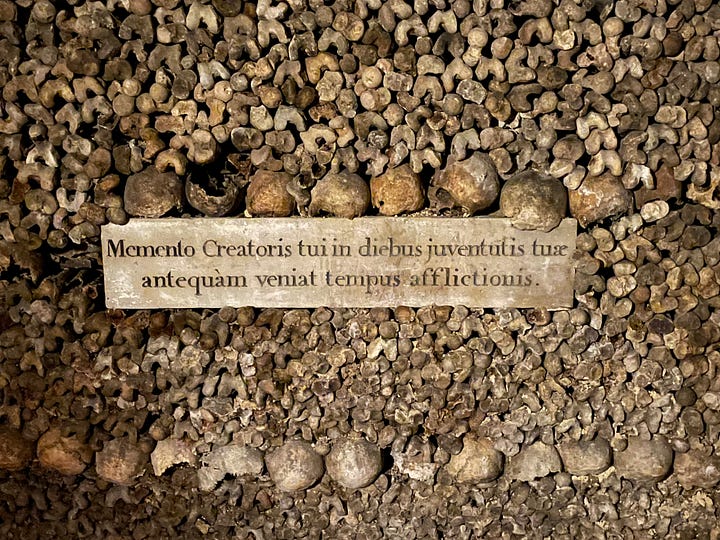

To echo British comedian Eddie Izzard, I have a somewhat morbid fascination with cemeteries—from La Recoleta in Buenos Aires to Center Street Cemetery in my hometown of Wallingford, Connecticut, I’ve sought out famous graves, beautiful stonework, and the secrets they hold. Last year, we visited the Catacombes in Paris, a 1.5-kilometer subterranean warren of tunnels lined with, even built from, the bones of some six million bodies. Visitors are greeted by the arresting inscription: Arrête! C’est ici l’empire de la Mort (“Stop! The empire of Death lies here”). Inside, the skulls of peasants rest on the femurs of noblemen—at least in death, the egalité and fraternité promised by the French Revolution rings true.

Highborn or low, this macabre maze was nobody’s first final resting place.

By the mid-1700s, Paris was swelling above ground and putrefying below. Overcrowded churchyards like the one at Saints-Innocents were essentially open mass graves, their “cadaverous miasmas” seeping into nearby homes. In 1765, the Parlement of Paris banned new burials within city limits, while in 1780 King Louis XVI condemned Saints-Innocents to death; a few years later, the Revolution would return the favor, and his own guillotined corpse would be tossed into a mass grave. Meanwhile, the remains from Saints-Innocents and other churchyards were exhumed and moved into the city’s old limestone quarries. Perhaps inspired by the legions of corpses his wars left on Europe’s battlefields, Napoleon ordered new rural cemeteries beyond city limits, including Père Lachaise—the world’s first “garden” cemetery. Meanwhile, the catacombs became a tourist attraction, even as bones continued to be deposited there up until Haussmann’s rebuilding of Paris in 1860.

As industrial cities swelled across Europe and America, each grappled with the same problem: how to make room for the living without erasing the dead.

For a time, the living had a tighter grip on the mortal soil.

Inspired by the French model, Britain and America reimagined cemeteries as venues for civic recreation. London’s “Magnificent Seven” garden cemeteries, opened from 1832, turned burial grounds into parklands, where picnicking among monuments became a genteel pastime of the Victorian “cult of death.” Today, these cemeteries remain tourist draws. Highgate Cemetery, where Karl Marx is buried, has a café, a gift shop, and toilets so that visitors can contemplate the commercialization of death. There, it’s not capitalism that’s late—it’s Marx.

Across the Atlantic, Mount Auburn Cemetery outside Boston pioneered the American version of the park-like necropolis with a landscaped cemetery that doubled as a botanical garden. Mount Auburn inspired copycats from Oakland in Atlanta to Laurel Hill in Philadelphia, birthing a national public parks movement. In New York City, officials had outlawed all burials south of 86th Street by 1851, prompting the creation of the so-called Cemetery Belt in Brooklyn and Queens, then at the edges of an expanding city and where many of Manhattan’s corpses would find their final final-resting places. Green-Wood, the city’s first garden cemetery, even inspired the later creations of Central and Prospect Parks.

Yet the closing of urban cemeteries and the opening of new rural ones did not mean that every burial was transferred. Chicago’s Lincoln Park began as the city cemetery, but an estimated 12,000 bodies remain under its lawns. In 1900, San Francisco banned burials within the city and over the next four decades exhumed 150,000 of its dead, reburying them in Colma—the “City of Souls”—but the remains of thousands still lie beneath the streets around Civic Center and Mission Dolores.

Other American cities have had to take different approaches to make room for the living and dead.

In New Orleans, the high water table made in-ground burials impossible—coffins floated up during floods—so the city built cemeteries above ground to keep the dead from rising again. Within these “oven tombs,” bodies bake in family vaults; after a year, the flesh is gone, leaving only bone that is then swept into chambers below the tombs. The tombs can then be reused, allowing historic cemeteries to stay in use and not merely in memory.

Back in Austin, Oakwood is a microcosm of America’s changing relationship to death, evolving from a haphazard folk graveyard into a gridded, landscaped civic space. Its grid was both functional and aesthetic, facilitating the sale of plots and strolls down “streets” of mourning. As the cemetery ran out of room by the early 1900s, Austinites complained about the cost of burial plots and the minimum plot sizes, foreshadowing the land use debates that would plague city politics a century hence. When the city expanded Oakwood in the early 1900s, the Annex reflected suburbanization trends: it curves in an undulating loop rather than extending the rectilinear order of the original City of the Dead.

By 1908, the city had formalized Sunday visiting hours, speed limits for carriages, dress codes for sextons—and the ban on dogs. The cemetery was codified as a part of civic life. It also codified in stone the social landscape: Oakwood’s original plots were segregated, mirroring the city that would later enshrine those lines in law. While the gravescape fixes one idea of Austin in time, the graves themselves tell a story of technological and aesthetic change. Railroads and mail-order catalogs democratized funerary art, making imported marble and zinc monuments available to ordinary families. Later, new carving technologies developed after World War II led to a proliferation of granite grave markers.

Today, the ornamental plantings and cast-iron fences of the Victorian era are gone, while the marble urns, obelisks, and angels fall into ruin. Names fade from grave markers and from living memory. The neighborhood doesn’t see very many new residents. Oakwood, a city within a city, exists within the fabric of Austin yet at the margin of human life.

Might it evolve or decay into something else?

While many urban cemeteries are designated historic landmarks, others now serve as green infrastructure—de facto storm-water buffers, wildlife corridors, horticultural centers, and carbon sinks—both supportive of urban life and yet starkly in contrast to it. Preservation and environmental concerns aside, the costs of transferring bodies are prohibitive, and our sanitized tastes can’t abide the notion anyway. The era of exhumation has passed, and death now holds these corners of our cities in its hands. Yet as cemeteries themselves show, nothing is fixed forever. Future generations may regard these urban graveyards less with reverence than with curiosity—wondering whether we struck a livable balance between the living and the dead.

We may find that while death is forever, cemeteries can also die. Memento mori.

So enjoyed this! Beautifully and thoughtfully written. Many thanks. My wife and I enjoy visiting cemeteries whenever we travel. In the spring we were moved by visits to both American and British cemeteries for veterans of D-Day and the subsequent battles for Normandy and later strolled the crowded Momartre cemetery in Paris where many notable cultural figures rest. I think how a respectfully cultures handle human remains is related to how much the values individual lives. A couple of thoughts on these competing for space in urbanizing areas. Might there be value in the reminder of our own mortality to soften resistance to change in a neighborhood needed to make room for the next generation? And in densifying places, as you point out, cemeteries can have value green space for strolling or picnics. As far as “carbon sequestration” goes, any green in a dense city will not be able to much relative to local emissions. Denser neighborhoods, on the other hand, are almost always “greener” than leafy or lawn-filled suburbs because they enable far lower per-capita GHG emissions from housing and transport. Counterintuitive, but true.

What I really want to know - what are the property tax, revenue, and trust structures that sustain cemeteries? The one we live next to is "full" (why?) and all maintenance except mowing is done by volunteers. Some day most of the graves will have no living family to care for it. What happens then? Luckily dogs are allowed