I'm Looking for a Man in Finance

Philanthropy and the Promethean Spirit

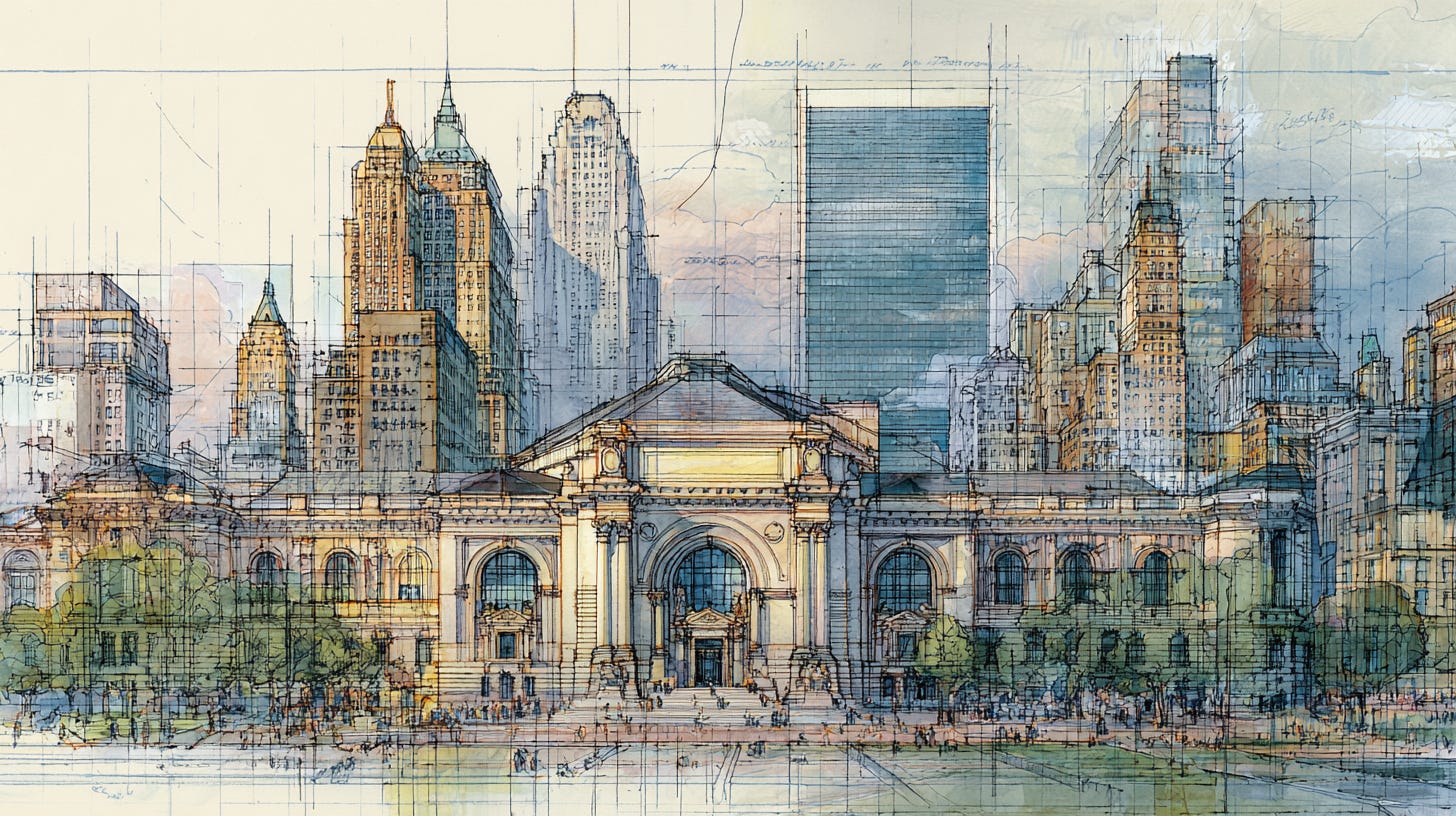

The Morgan Library sits proudly on a corner of Madison Avenue in Midtown Manhattan, an ornate Italianesque palazzo housing a treasure trove of rare manuscripts, books, drawings, and prints—and a recently discovered Chopin waltz. Once the personal library of financier J.P. Morgan, today it is a public museum, a research institution, and a delightful way to spend an afternoon. The library is not only a monument to Morgan’s love of the arts, it’s a legacy of his sense of public-spiritedness—one that seems sorely lacking in our modern era.

I visited the Morgan Library during my annual summer pilgrimage to New York last August, a few months after TikToker Girl on Couch went viral for a silly video in which she sort of sings:

I'm looking for a man in finance / Trust fund, 6'5", blue eyes

Standing 6’5” with a tophat, arched eyebrows over piercing, dark eyes, mustache drooping under a bulbous nose, J. Pierpont Morgan loomed over Wall Street in his lifetime—and not only for his physical appearance. Undoubtedly, his most far-reaching impact was as the Captain of Industry who transformed America’s fledgling economy into a global powerhouse and made Wall Street more than just a name on a map. He made his fortune funding “trusts” like US Steel and General Electric, he financed the electrification of New York and the construction of the Panama Canal, he cavorted with kings and kaisers, presidents and popes, and the stock market rose and fell on reports of his health. It was for all this that Morgan would come to be feared and loathed, his reputation as a “Robber Baron” seared into the public imagination by the muckraking journalists of his time, who falsely reported that Morgan had declared, “I owe the public nothing.”

To many it felt true, and Morgan’s reticent public persona didn’t help, but his legacy tells a somewhat different story about his relationship to the public.

J.P. Morgan’s epitaph could read like the inscription on Sir Christopher Wren’s tomb in St. Paul’s Cathedral: Si monumentum requiris circumspice. If you seek his monument, look around. Across New York, Morgan’s monuments dominate the cultural landscape: not only his eponymous library, but also the uptown Metropolitan Museum of Art and the American Museum of Natural History, social clubs like the Metropolitan and Yacht Clubs, the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. When I looked around New York last summer, I wondered: where are all the men in finance like him today?

Morgan was a prodigious collector and patron of the arts, and one of the most generous benefactors of his time. He put his talents not only toward building modern industrial companies, but to building up nascent cultural institutions. Morgan served as a founding trustee of the Natural History Museum for 44 years and had a 42-year relationship with the Met, serving as its president from 1904 until his death in 1913. In that position, he used his organizational acumen and access to capital to transform the Met into a world-class institution.

As his biographer Jean Strouse puts it, he spent these years “stocking America with the world’s great art.” By 1912, he had spent nearly $60 million of his own money—nearly $2 billion in today’s dollars—assembling his personal collection. His will instructed his heirs to distribute much of it to various institutions to “render them permanently available for the instruction and pleasure of the American people.” He would bequeath more than 7,000 works of art to the Met alone. Today, of course, the institutions to which he gave his talents and capital are as fixed in the tapestry of New York as he was in life, iconic, even beloved. He poured resources into ensuring this would be so, investing his time and treasure to build institutions that would last.

The question was why he bothered. As Strouse notes,

Born into a wealthy family, Morgan had a patrician sense of noblesse oblige and unusual motivations: he could have made a lot more money than he did, if that had been his primary aim, and unlike many sons of rich men, he worked hard all his life.

He had unusual motivations indeed.

After his death, the Met eulogized this “Great Citizen of Great Heart, Great Mind, Great Will,” concluding of him, “Knowing that art is necessary to upholding the ideals of a nation he gave to this Museum generously of his possessions and more generously of himself.” Fellow banker Frank Vanderlip remarked, “Mr Morgan, typical of the time in which he lived, can have no successor, for we are facing other days.”

Morgan was not principally motivated by charity, nor by feelings of guilt—outside of financial transactions, it was never about what he “owed” anybody. He was not preoccupied with modern notions of “giving back”—after all, the companies he financed brought Edison’s lightbulb to the masses and steel for skyscrapers that punctured America’s spacious skies, for bridges that spanned its mighty rivers, for railroads that sliced across the fruited plain, for the equipment that harvested America’s amber waves of grain. Nor was philanthropy a means of climbing the social ladder—he was already at the top of it, anyway—and it wouldn’t explain why he spent more than forty years providing pro bono services to the institutions he cherished.

Rather, as the Met eulogy suggests, Morgan had a sense of something else: an appreciation of the role of art in the cultural life of his country, and the patriotic public spirit to deploy his talents toward cultivating it. If Robert Moses was Ozymandias, J.P. Morgan was Prometheus.

Morgan assumed “moral responsibility” for the success of America because he believed it was “the thing to do,” but also because he saw his own destiny as wrapped up with that of his young, industrializing country. His personal librarian, Belle da Costa Greene (a fascinating figure in her own right), wrote that he aspired “to be a builder—not a wrecker in the world of things.” He invested in the cultural capital and success of his city and his country because he loved the arts, because he loved his home and homeland, and because he loved his countrymen.

J.P. Morgan was motivated by philanthropy in the most fundamental sense—love for humanity. To the public he owed nothing, he gave quite a lot.

That love was not always reciprocated in his own time, and seldom in ours. Nevertheless, my interest here is not to rehabilitate Morgan’s reputation. Strouse’s biography, Morgan: American Financier, does a fine job of situating him in the full context of his many accomplishments and complications. Rather, it’s to highlight that spirit that seems missing in our own times, but which, perhaps, we are grasping to rediscover: the aspiration “to be a builder—not a wrecker in the world of things.”

Morgan understood that institutions—cultural, civic, corporate—strengthened our young republic and built them in the Gilded Age. Today, we are facing other days, indeed, in this meme-inflected age of irony and mockery, where it’s much easier to be a wrecker of dreams than a builder of enduring legacies. If we, as a nation, have lost the capacity to build as Morgan did, it is in part because we have lost our sense of philanthropy.

Instead, today’s so-called philanthropy often feels disconnected from such long-term vision and public-spiritedness. Much of modern charity is superficial, performative, self-serving. Sam Bankman-Fried has become the poster-child of this phenomenon: his meteoric rise as a proponent of “effective altruism” collapsed in a spectacular failure that betrayed not only financial fraud but also his utter disdain for lesser mortals. Meanwhile, the annual Met Gala reduces the museum and its contents to a mere backdrop for the fashionable and famous, while other “charity” devolves into lavish parties, executive perks and private jets, and “starchitecture.” On Giving Tuesday next week, we’ll all be asked to give to causes aplenty—but do we care about our values enough to ask whether it is being put to good use? True philanthropy is more than writing checks, more than a dinner plate on the charity circuit, more than slapping one’s name on a building and swaddling oneself in irony and satin. In what passes for philanthropy these days, there’s no real love in any of it.

True philanthropy requires an investment of goodwill in your fellow man.

On this Thanksgiving, J.P. Morgan’s legacy is a reminder that true philanthropy is not merely transactional—it’s a reflection of our love for the world and our fellow man. In our age of performative charity and half-gestures, we ought to be thankful for those whose far-reaching, benevolent vision has endowed us with such a rich cultural inheritance. But gratitude alone is not enough. We can honor that legacy by paying it forward, by investing our time and money, sure, but especially our goodwill in the causes and communities we love. We needn’t go looking for a man in finance. To be a “Great Citizen of Great Heart, Great Mind, Great Will,” we don’t even need great wealth—only a Promethean spirit.

Thank you to all readers of City of Yes! I’m incredibly grateful for your support and wish you and your loved ones a happy Thanksgiving and holiday season.

Who is this hip, tik-tok-trend aware writer!?

"True philanthropy requires an investment of goodwill in your fellow man."

This is so good, it may one day be falsely attributed to Einstein and circulated like a mid-aughts meme.