It’s Gay Pride Month again, so many partisans and pundits will spend the social calendar’s most colorful month pearl-clutching and posturing. While they fight the culture war, the rest of us can enjoy the season and its myriad events. Gays, straights, and everyone in-between will turn out in droves for the festivities, flying miniature rainbow flags, marching in drag or lip-syncing in speedos, and cruising in drop tops wearing crop tops or mayoral sashes.

Even though I’m both part-Irish and full-gay, I’m not super partial to parades, but I do enjoy the festive atmosphere this time of year. When I lived in San Francisco—Where Every Month is Gay Pride Month™—the city would deck the halls of power with rainbow flags and light displays, residents would festoon their Victorian homes with colorful bunting, and businesses would don their logos in, and sometimes sell, gay apparel for the holiday season.

It was a fun time. But…all the rainbows and glitter masked the darker reality of the city’s downtown streets. Amidst the homeless encampments, the discarded needles, the schmears of human feces, the locked up items in convenience stores, the shattered car windows—I would think, if only San Franciscans felt as proud about their city.

Where was the civic pride?

This is not only a San Francisco problem. Even before the pandemic presented cities with a host of new problems, they had many denizens who liked to bitch about the state of things, even some who seemed to revel in urban decay so long as it confirmed their partisan priors. But there were few who actually seemed to be doing anything about it, and so it’s no wonder that so many people gave up and left over the past few years.

In their hearts and minds, their cities didn’t have pride of place. What would it mean if they did?

Understanding Gay Pride can help here. Gay Pride is not the superficial celebration of an unchosen, innate characteristic. It’s much deeper: it’s a recognition of the dignity of gay people, an expression of their self-worth, and an embrace of their right not only to exist but to do so with full citizenship. Ultimately, Gay Pride is about personal agency, self-love, and civic participation.

By extension, to be an ally of gay people is to do more than fly rainbow flags, or march in Pride parades, or dole out corporate sponsorships. It’s to vote for gay marriage, to attend our weddings, to welcome us into your homes and workplaces. To really celebrate Gay Pride is to do more than say you recognize our dignity, it’s to take that support and turn it into meaningful action.

If that’s Gay Pride, then civic pride is a recognition that one’s city is valuable and worth saving, an expression of concern for its long-term viability, and a demonstration of public and political action to fight for a better future and against the things that are making it unlivable.

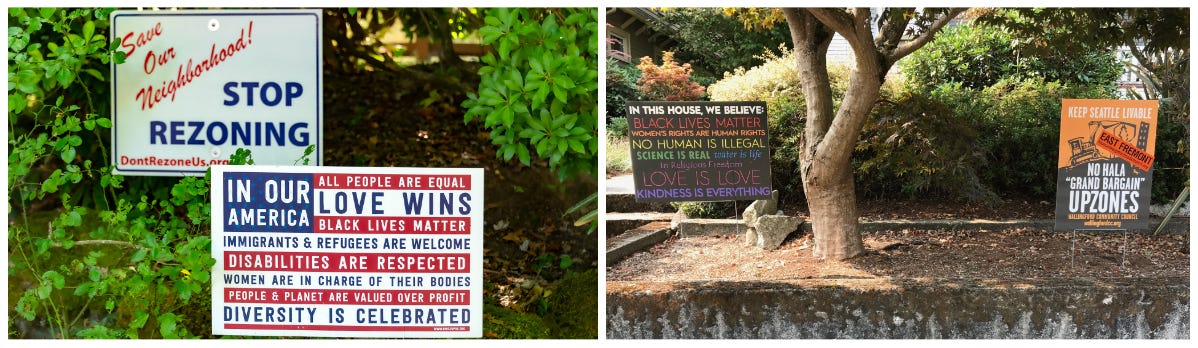

Civic pride certainly isn’t this—take a close look:

You can find this kind of juxtaposition in many cities.

In particular, when you walk through San Francisco’s tonier neighborhoods, you’ll see lots of Pride flags alongside the ubiquitous “Black Lives Matter” signs—the virtuous signals of their progressive support for marginalized people. And then they will vote for members of the Board of Supervisors who will mouth platitudes, make excuses for the deteriorating status quo, and then oppose the construction of any and all new housing that might allow marginalized people to live in their neighborhoods. Up in the exclusive Victorian mansions where the marine layer whispers its cleansing breath across the city’s hills, everything is glorious and pure—the problems of the downtown street are out of sight, out of mind.

Love wins, but housing loses. No human is illegal, but their housing is. Black lives matter, but they can’t live here. Diversity is celebrated—at the grandstand but not at the ballot box. So much for inclusivity.

It’s all words without deeds—or deeds that put the lie to their words. How could they have civic pride when they don’t take the civics part of gay-or-any-other pride seriously?

If these folks seriously wanted an inclusive city, they’d offer more than an empty welcome message. Instead, the message many of our cities have been offering, through their actions and inactions, is one of exclusion—not just to all the marginalized subgroups on the “In This House…” signs, but to middle- and working-class individuals and families more broadly. A city becomes unwelcoming when its policies have made it unlivable—too expensive, too unsafe, too dirty, too incompetent, too corrupt, too exclusive…except for those who have insulated themselves or benefit from the status quo of urban stagnation and decay.

To have civic pride is to do more than lay out a welcome mat. It’s to take the real concerns of real citizens seriously—and to go to the mat for them.

It’s not just about housing, though no city can be welcoming without taking measures that legalize the building of more and different types of homes. Liberalizing zoning, streamlining permitting, and combating entrenched NIMBY opposition to create more housing is a necessary but not sufficient condition of inclusivity.

Civic pride is also about taking public safety seriously, recognizing that “safe streets” require more than multimodal mobility investments and satisfactory sanitation services. It means recognizing that car break-ins, auto thefts, shoplifting, and fare evasion, are not hassles to be tolerated but crimes that erode social trust and have real costs for residents, business owners, shop workers, and public finances. It means recognizing that we need better-funded, better-trained, more responsive, and community-based police officers and emergency services—and affordable homes for those first responders in the communities they serve.

It’s about recognizing that homelessness is a profound human tragedy to be overcome, not a nuisance to be ignored—nor one that will be solved by sweeping away encampments or throwing more money at a panoply of Non-accountable Grifter Orgs. Taking it seriously means building more shelters and supportive housing, getting mentally ill and drug-addicted folks into treatment centers, cleaning up public spaces for public use, and most important of all, providing enough housing and support to prevent people from ending up on the streets in the first place.

And it’s about recognizing that families won’t stay if childcare is rare and unaffordable, if the schools fail to provide a solid education, if the public infrastructure is not people-centric, if there aren’t enough family-friendly housing options, or if parents don’t feel that their children are safe.

Whether it manifests as an increasing cost of living, a deteriorating quality of life, or a decline in public safety and services, these are problems of urban decay for which we should have no patience, and ones that we should be eager to solve.

To have civic pride is to say we can do better—and then to do it.

In San Francisco, rediscovering civic pride is literally an uphill battle, but this is an every-American-city problem. Recovery from the trials and tribulations of recent years will only come if cities are able and willing to welcome more people and retain those still there. They have to get all the livability aspects of city life right. There are lots of people working on that in our cities right now—but we need more leaders who can demonstrate civic pride and inspire more citizens to get on board with the project of setting things right.

This Pride Month, by all means, let’s fly the flags and march in the parades. But if we really want to build better, more inclusive cities—ones that all types of people can truly live and take pride in—we’re going to have to do some serious work.

City of Yes is a free publication, but a paid subscription is a meaningful endorsement of our work in building a better civic culture and urban future. We’re happy to have you, either way. Thank you for reading, and happy Pride!

Further Reading for a Happier Pride:

Yaaas In My Backyard

Why are so many legislators gay for housing. Is it a reflection of good taste? Or is there something inherent in homosexuality that predisposes these gays to favor more housing, beyond a desire to decorate more homes?

Is that what the Gay Agenda was all about?

Loved this read! Happy pride!