Supply, Demand, and Housing Affordability

Lessons from Minneapolis to New Rochelle

Note to readers: I’ll be writing from the road for most of August, so posts may land on a more erratic schedule. Also: I’ll be in New York the week of August 18th—reach out if you’d like to meet up in person! Have a great weekend!

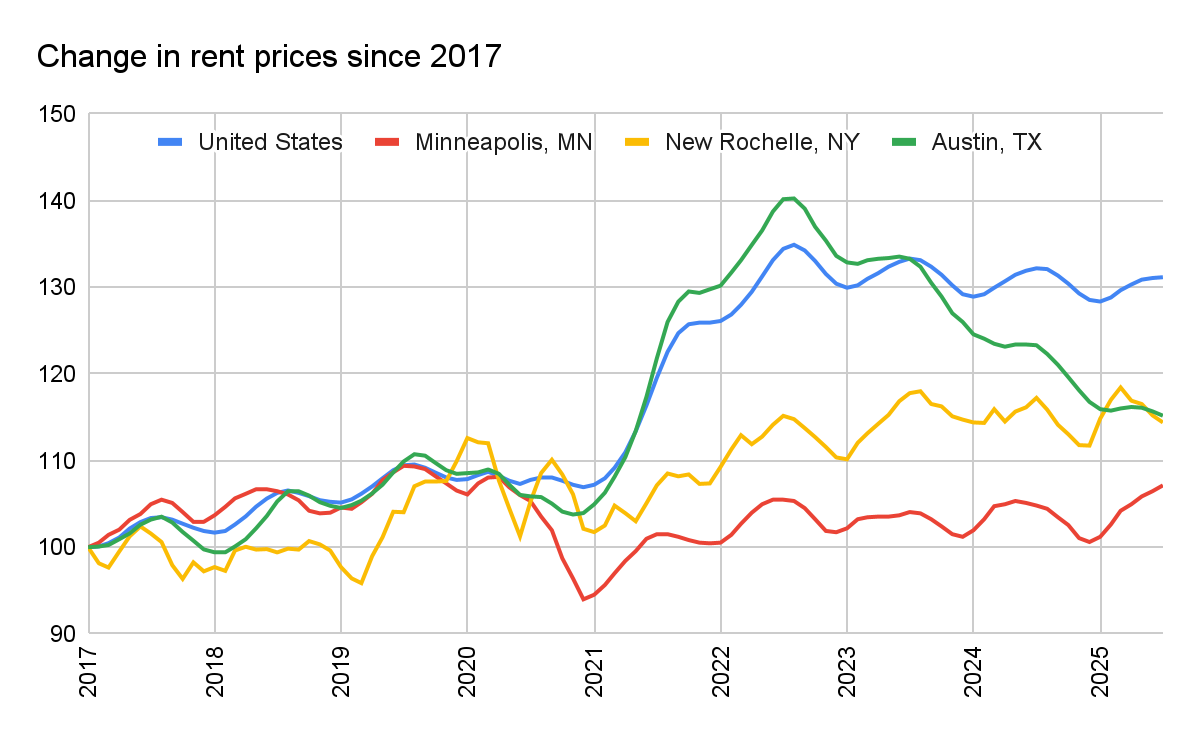

The other day, Tyler Cowen posted on Marginal Revolution about a new study showing that Minneapolis’s zoning reforms are responsible for the city’s sustained affordability. Defying the national trend, rent growth in Minneapolis has underperformed inflation as housing costs elsewhere have soared. Aha!, thought I—another YIMBY victory to write about. But as I read the study and did some further research, I found myself getting stuck on the study’s thesis: Minneapolis’s reforms didn’t trigger a construction boom; instead, housing demand softened, “likely driven by altered expectations about the housing market.”

In other words, the study suggested that a city could achieve housing affordability merely by passing zoning reforms. The reforms didn’t actually have to create new housing. My “aha” moment became more of an extended “hmm.”

The study’s thesis sounds almost magical—like you could wave the wand of zoning reform and prices would ease without a single new building going up. But housing markets don’t work on magic. Most people don’t even notice zoning reform. I know this because every time I show up at City Hall to support zoning reforms, it’s the same 100 activists. At Zoning & Platting Commission meetings, where I serve, the audience is almost entirely land-use attorneys and city staff. Most humbling of all, I’ve even been asked at a housing conference to explain what “upzoning” is. Most buyers and renters don’t respond to zoning changes at all; they react to housing that’s actually available, to prices, to mortgage rates, to other bidders.

The “great expectations” hypothesis fails to meet expectations about how normal people actually behave in the marketplace.

Minneapolis has been held up in recent years as the model of zoning reform done right. Its 2040 Plan legalized up to three homes by right on lots restricted to single-family houses, scrapped parking minimums, and encouraged denser development near downtown and transit. With 70% of residential land previously locked into single-family use, these were sweeping changes—on paper, at least. According to the study, in the five years after implementation, home prices grew 16% to 34% less than they would have without the reform, and rents grew 17.5% to 34% less. The biggest gains were for condos, smaller homes, and lower-priced segments—meaning modest-income buyers and renters benefited most.

Compared to other cities where prices skyrocketed, it reads like a stellar success story.

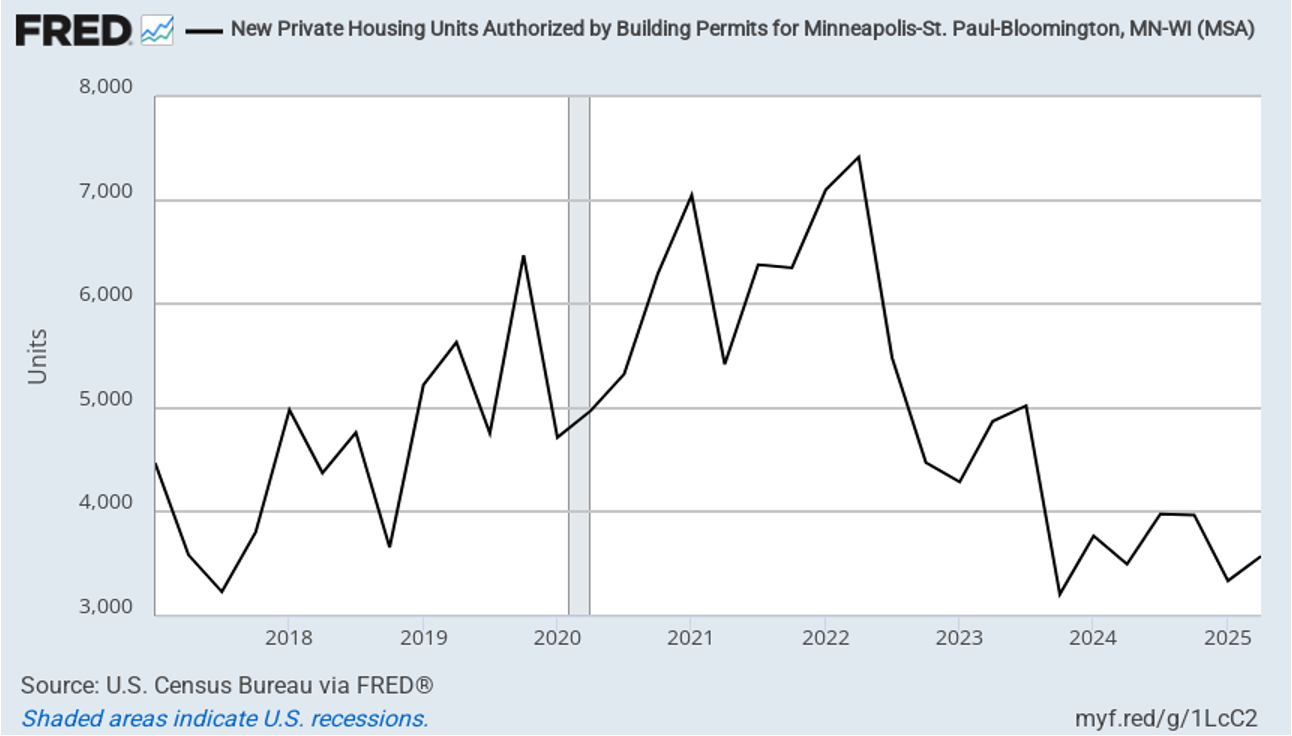

And yes, the city did see housing gains. A recent Pew analysis found that the city's housing stock rose 14.5% from 2017 to 2023, far ahead of many peers. But most of that growth came early, and very little came from the duplexes and triplexes the plan was supposed to unleash, as Zak Yudhishthu has explained. Instead, developers took advantage of upzoning along corridors to build mid-sized multifamily buildings, and just over 1,000 additional units were issued permits from 2020 to 2023. That’s not nothing, but it’s unlikely in a city of 428,000 people to reduce housing costs by 16% to 34%. Meanwhile, since 2022, permitting has slowed sharply—partly due to a now-dismissed environmental lawsuit that stalled development, but also because softer demand has reduced incentives to build

Several factors point to weaker demand. The city’s population has edged down since 2020. Unrest following George Floyd’s murder may have dampened in-migration. And earlier supply gains may have satisfied much of the market’s demand at current prices, making new projects less profitable. Together, these shifts help explain why rents have stayed stable even without a sustained construction boom.

In short, Minneapolis’s stability owes as much to cooling demand as to added supply—an important distinction for cities hoping to replicate its results. This is of particular relevance to a city like Austin, which in the past couple years has largely followed the Minneapolis reform playbook—might it not matter? One key difference is that in the first fifteen months since Austin legalized triplexes in single-family neighborhoods, nearly 800 new homes have been proposed taking advantage of the new zoning.

Nevertheless, these units are still under construction and cannot be credited with bringing down housing costs in Austin—where rents have dropped 22% from recent peaks. That is a factor of a sustained building boom and softening demand, now that the pandemic in-migration rush has ebbed.

If Minneapolis shows how cooling demand can hold prices down without a building surge, and if Austin shows what happens when surging supply outstrips demand, New Rochelle, by contrast, shows what it looks like when a city meets high demand with high output and still keeps rents in check.

Since 2020, while rents across the New York City metro have jumped 25% or more, they’ve risen just 1.6% in New Rochelle. Was this because renters’ expectations changed after an upzoning?

Of course not. This small city of 85,000 people built a ton of housing, with 11,000 units completed or underway, increasing the city’s apartment stock by 37% over the past decade. And they made sure developers would actually build: “New Rochelle streamlined environmental reviews, offered developers tax incentives, and created standardized zoning rules to make it easier and cheaper to build homes,” while assuring a 90-day approval process for residential projects if certain criteria were met.

What’s most revealing is that New Rochelle succeeded by actively courting growth. In 2014, the mayor partnered with a developer on a downtown master plan. It was approved in one year—compared to the decade-plus typical in the region. The city then approved thousands of apartments in one go, avoiding piecemeal rezonings. That bold strategy attracted $2.5 billion in development and thousands of new residents priced out of New York City.

Of course, with growth comes growing pains, and some longer-term residents have organized to oppose further development, demand developer concessions, and lobby for rent control. But New Rochelle shows that the best rent control policy is to build more housing.

So, what are the takeaways from all this?

We should be skeptical of claims that passing zoning reform matters more than the results of zoning reform. Markets respond to both supply and demand, often in ways that make cause and effect hard to untangle. And affordability isn’t always a sign of success—especially if it comes from economic stagnation or weakened demand.

The bigger lesson is for coastal cities that have struggled to build housing—especially the metropolis just 40 minutes down the railroad from New Rochelle. New York City will elect a new mayor this November, and the frontrunner is talking a lot more about freezing the rent rather than unfreezing the city’s housing market. As people from his city continue to get priced out to New Rochelle, he should hop on the train and see how they’re actually delivering affordability there.

He might then have his own “aha” moment.

Good article with lots to think about.

One nitpick: I agree that it's unlikely 1,000 additional units being issued permits from 2020 to 2023 would reduce housing costs by 16% to 34%, but it's not that surprising if home price *growth* slowed by that amount, as you suggested nearer the beginning:

> According to the study, in the five years after implementation, home prices grew 16% to 34% less than they would have without the reform, and rents grew 17.5% to 34% less.

Your piece is good. My own view is that cities need an "all of the above" approach to housing. By all means, clear the bureaucratic and regulatory brush to streamline permitting. By all means, remove zoning restrictions against density. By all means, use antitrust in cases of collusive or oligopolistic behavior (e.g., RealPage's algorithmic pricing offerings to landlords). But also, let's not loose sight of the need for basic policies that encourage economic growth. I can't comment on Minneapolis city policies in particular but I would point out a possible linkage between lower housing demand and the fact the Minneapolis economy has underperformed: Minnesota's real GDP growth averaged 0.9% annually from 2019-2022, which was roughly half the rate of the U.S. economy. The region also saw a decrease in business incorporations in the first quarter of 2015. Credit: Gemini. My point being that growth should drive housing demand, which, if the housing policies (see above) are right, should drive construction and supply, and ultimately, we hope, affordability.