Decongesting Economic Opportunity

Encouraging the Free Flow of Commerce in the City of Yes

While the news in New York City last week was dominated by Governor Kathy Hochul’s potentially illegal pause of a much-anticipated traffic congestion pricing plan, another important milestone got overshadowed. The day after what I’m calling “No-Tollgate,” New York’s City Council passed Mayor Eric Adams’s City of Yes for Economic Opportunity program. The program represents a “comprehensive overhaul of New York City’s zoning rules to support small business and entrepreneurs, foster vibrant streetscapes and commercial corridors, and boost New York’s continued economic recovery.”

The Economic Opportunity reforms simplify or remove certain rules and restrictions that limit where and how commerce can happen in the city—a laudable goal given that job creation in New York has stalled and unemployment remains above the national average. Among the changes, the city liberalized regulations around home-based businesses, will allow commercial uses on the upper floors of mixed-use buildings, and expanded the types of uses allowed in commercial zones to include things like microbreweries and indoor agriculture. It also legalized dancing in New York bars for the first time since Prohibition—life truly is a cabaret!

New Yorkers may not be dancing in the street yet—after all, those streets are still clogged with vehicles from New Jersey and Long Island—but the passage of the reforms is welcome in a city that has long made it difficult for small businesses to operate.

It’s also an implicit recognition that the business of urbanism is about more than building housing; a city is, fundamentally, more than just a place to live. As we’re seeing across America and as we’ve chronicled here, cities stop working when they don’t produce enough housing, but they also stop working when there’s not enough work.

A place without commerce, without economic opportunity—such a place is not a city at all.

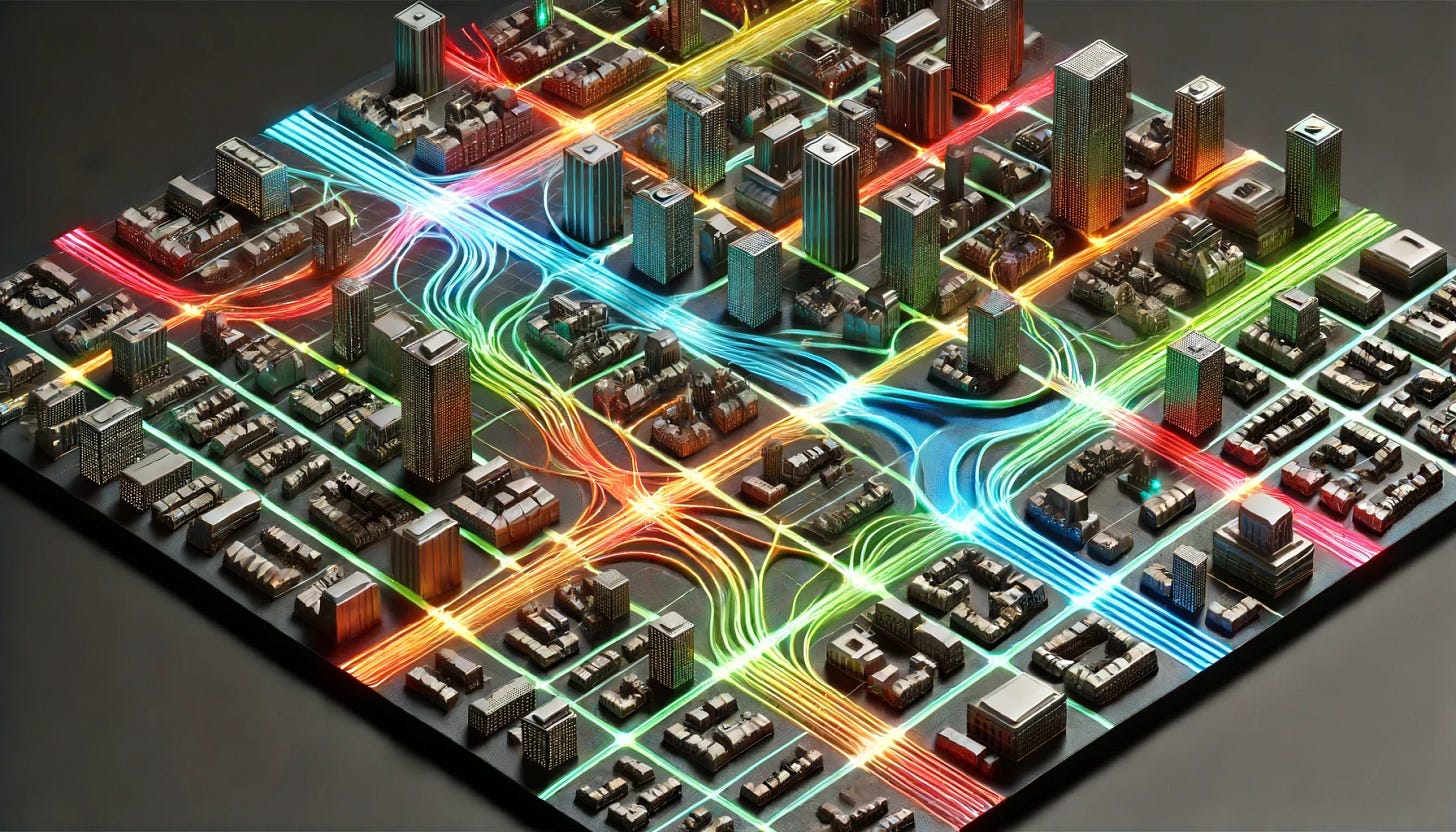

Commerce is at the heart of the city, and economic opportunity is its lifeblood. Cities are economic opportunity engines, spinning out new businesses, new jobs, new ideas, new culture. They generate wealth, knowledge, innovation, and fun. Yet so many cities, rather than vigorously greasing the wheels of this opportunity machine, can’t help but throw sand in the gears.

Unfortunately, the culture of “no” has become commonplace in many big cities. As someone who opened and operated small businesses (preschools) in New York and San Francisco, I never encountered a bureaucrat who saw their job as helping us get to “yes.” While many well-meaning people are attracted to public administration, such bureaucracies often become breeding grounds for incompetence and sclerosis. Occasionally, for malice. There are no incentives to be responsive, timely, or efficient for the citizens they are ostensibly there to serve.

A few examples paint the picture. When I was renovating an entire preschool in Encinitas, California, our contractor was able to get a building permit in one day. When I was attempting to secure a permit for a one-room renovation in San Francisco, it took months of review, with no transparency into the process or timeline. On a separate occasion in San Francisco, we passed on leasing a new building to expand our elementary program because the fire department’s planners could not agree amongst themselves what their own regulations said we were allowed to do at that building.

At my New York preschool, we were required to build an exterior wheelchair ramp that had to comply with the conflicting requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act, the Dept. of Transportation, the Dept. of Buildings, the Dept. of Health, the Landmarks Preservation Commission, and the fire department. There was no law of physics that could produce a legally compliant ramp, and so the only viable solution was to (expensively!) lower the lobby of the building by eleven inches to street level.

For the same project in New York, I had to hire a bevy of permit expediters and lobbyists to grease the palms of bureaucrats and elected officials to obtain the temporary certificate of occupancy that would enable us to get our preschool license. That was on top of the historic preservation consultant we needed to navigate the city’s landmark requirements. Together, these consultants cost us tens of thousands of dollars, but the time lost dealing with byzantine processes—an extra year—cost us millions in foregone revenue and rent payments on an empty building.

This is just my experience—but it will be familiar to anyone who has tried to open a restaurant, a bodega, an ice cream shop or any other type of small business in a big city.

Basic competence and efficiency in public administration is a necessary precondition for creating economic opportunity, yet we see this need taken for granted time and again. Besides the challenges of rejuvenating urban prospects post-pandemic, cities face enormous public problems around homelessness, schools, and infrastructure. But if they can’t pave their potholes, if they can’t pick up the trash, if they can’t issue permits, if they can't build a public toilet—if they can’t do the basics, they certainly can’t be expected to solve the big problems.

Of course, lousy public administration often flows directly from lousy policy—and unfortunately our cities are rife with it.

We have cataloged the myriad ways that urban land use has made cities inhospitable to human habitation, but many cities have been outright hostile to business. Punitive taxation and fees, exclusionary commercial zoning, expensive and arbitrary licensing and permitting regimes, cumbersome and overcautious environmental regulations, inflexible labor laws, a culture of NIMBYist public input—all of these stifle economic opportunity by limiting where it can happen, who can participate, and how things must be done.

To get cities back on track, the wheels must come off the tired, corrosive idea that commerce exists to feed the coffers of a non-accountable grifter org (NGO)-administrative complex, when it is instead the reason the city exists in the first place.

In New York, Mayor Adams saw that the city was stifling economic opportunity due to its own mess of arbitrary and punitive policies. Provided the City Council also passes the mayor’s housing reform program, New York will have taken big steps in the direction of long-term recovery. But the scope of the problem is huge, and I suspect the city still has lots more policy and administrative reform to undertake to create a climate that is truly supportive of small businesses, workers, and the middle-class.

Incidentally, that brings us back to New York’s congestion pricing debacle. While Governor Hochul averred her eleventh-hour change of heart was due to concerns the imperfect program would hamper the city’s economic recovery, it appears her motivations were more cynical. Nevermind the political calculations she made, which seem likely to backfire. Her decision robs the Metropolitan Transit Authority of billions in anticipated funding by sparing 284,000 suburban drivers from contributing to the cost of roads that New York City taxpayers provide. Worse, the governor’s alternative proposal was to raise payroll taxes, a move that would have impacted more than four million New York workers. Fortunately, that proposal was dead-on-arrival in the state legislature, but it’s revealing that the governor thought raising taxes on New York’s beleaguered commercial activity would somehow spur economic recovery—it suggests that she doesn’t actually understand what’s ailing New York.

And that’s the irony. Commerce is not only about the buying and selling of goods and services, but also about their traffic. Congestion pricing is a proven way to reduce discretionary vehicular traffic and raise revenue—while making it easier for delivery trucks, cargo vans, couriers, taxis, buses, and emergency services to circulate within a city. In other words, it improves the flow of commerce.

Incidentally, there’s an older usage of the word “commerce” that means “social intercourse”—the trading of information. As the Mayor and City Council of New York undertake necessary reforms to spur economic opportunity, perhaps it’s time for Governor Hochul to traffic in some new ideas.

Weirdly enough, I did find one city that actually wanted to get you to yes. Chicago. No, their rules weren’t perfect and they had plenty of bureaucratic overhead. But Chicago BACP actually did want you to succeed and did a pretty unique job holding your hand through the process so that you could open.

You’d never think it’d be Chicago…but it’s Chicago.

Oh, but you’ve got to explain the TCO shuffle!

Tl;dr - nearly every building in NYC is on a neverending string of Temporary Certificates of Occupancy. (TCOs) The reason being that NYC Dept of Buildings won’t issue a final CO until every single permit, project, inspection, fine, or fix is cleared in the whole building. And in a city full of skyscrapers, the day when everything is 100% perfect never comes. So you can have a building that’s been shuffling through TCOs every couple of months for decades.