The Never-Ending Housing Emergency

How Rent Control Arrests Development

The sitcom Arrested Development follows the wealthy but dysfunctional Bluth family after patriarch George—a caricature of the greedy developer—is arrested for fraud. In one now-memetic scene, as daughter Lindsay and her hapless husband Tobias try to fix their marriage, Tobias suggests they pursue an open relationship, something he’s recommended to his therapy clients. Lindsay asks, “Well, did it work for those people?” Tobias replies, “No, it never does...but it might work for us.” Alongside the imprisoned paterfamilias and the stalled real estate business, the scene captures a third meaning of the show’s title: the self-delusion of people who refuse to grow up.

This scene came to mind as I read Rogé Karma’s Atlantic article arguing that New York’s mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani “has a point about rent control.”

Mamdani’s narrow win over the disgraced former governor Andrew Cuomo—who, like a Bluth, seemed to think he was entitled to the job—was built on a simple message of affordability, with his signature “freeze the rent” policy as its centerpiece. In a city where more than half of renters pay more than a third of their income on rent, Mamdani’s proposal would halt annual rent increases for New York City’s nearly one million rent-stabilized apartments. Because New York City is a bellwether for progressive politics nationally, I suspect we’ll be hearing a lot more about rent control over the next few years.

Rent control may win elections, but it doesn’t build housing—and New York’s own experience suggests that expanding it might be, to borrow a trope from the show, “a huge mistake.”

My aim here is not to rehash the arguments against rent control. Ninety-eight percent of economists—from Paul Krugman to Thomas Sowell—agree that rent control does more harm than good. By capping prices, it discourages new construction, raises rents for unregulated units, and leads landlords to disinvest in properties. (Here, I’m using “rent control” broadly to include any system that restricts how landlords set rents, including rent stabilization).

Karma concedes rent control’s economic flaws but claims it may be politically necessary—not because it makes housing markets work better, but because it makes housing politics work better. It’s “a clear political winner,” he writes, citing polls showing 75–85 percent voter support, since “unlike the process of building new housing, passing a rent-control law can deliver tangible benefits almost immediately.” That popularity is easy to understand in places where the housing system barely functions. Across much of urban America, restrictive zoning, endless discretionary reviews, and an “everything bagel” of environmental and labor rules have throttled supply. Given that reality, it’s little wonder people don’t trust “the market” to deliver.

Housing experts likewise argue that pairing rent stabilization and other tenant protections with zoning reform has been the only way to get housing bills passed in blue states. For his part, Mamdani says, “we absolutely have to expedite the process by which we build new housing…but we can’t do that unless we also address people’s immediate needs.”

In other words, we need rent control today to get support for the housing we need to build tomorrow. There’s a certain logic to this—but the evidence that rent control improves the politics is weak.

Insisting that there’s a “growing body of real-world evidence” to back up this thesis, Karma cites a research paper from Berlin that found that people “who lived in rent-controlled apartments were 37 percent more likely to support new local-housing construction than those living in noncontrolled units.” This is interesting, but it’s not in itself conclusive, especially when real-world conditions in the United States offer counterexamples. San Francisco, long under rent control, voted twice in favor of expanding it in statewide referendums while routinely blocking housing. Meanwhile, Austin—where rent control is illegal—passed meaningful zoning reform, built abundantly, and saw rents fall.

In his article, Karma also quotes UC Davis law professor Chris Elmendorf, citing a study he co-authored that surveyed 5,000 people about their views on housing. The study found that people generally have ill-informed views of what (and who) drives housing markets and favor punitive policies over zoning reform. Karma highlights the finding that rent control is popular, but omits the authors’ larger warning: that such enthusiasm often reflects “folk economics,” not sound policy. Elmendorf and his co-authors conclude that people will support almost any policy that promises to lower housing costs and embrace blame narratives that cast the archetypical greedy developer in a starring role—regardless of the merits. They caution that “enthusiasm for quick fixes in the housing domain could very well crowd out or vitiate the legislative victories that YIMBYs have scored thus far.”

The tragedy is that rent control channels real fear about housing scarcity into policies that perpetuate it. If Elmendorf is right that rent control endures because it flatters our economic folk tales—casting landlords as villains and tenants as victims—then its persistence isn’t surprising at all. It’s a story we keep retelling because it feels right, not because it is right. And nowhere has that story run longer than in New York.

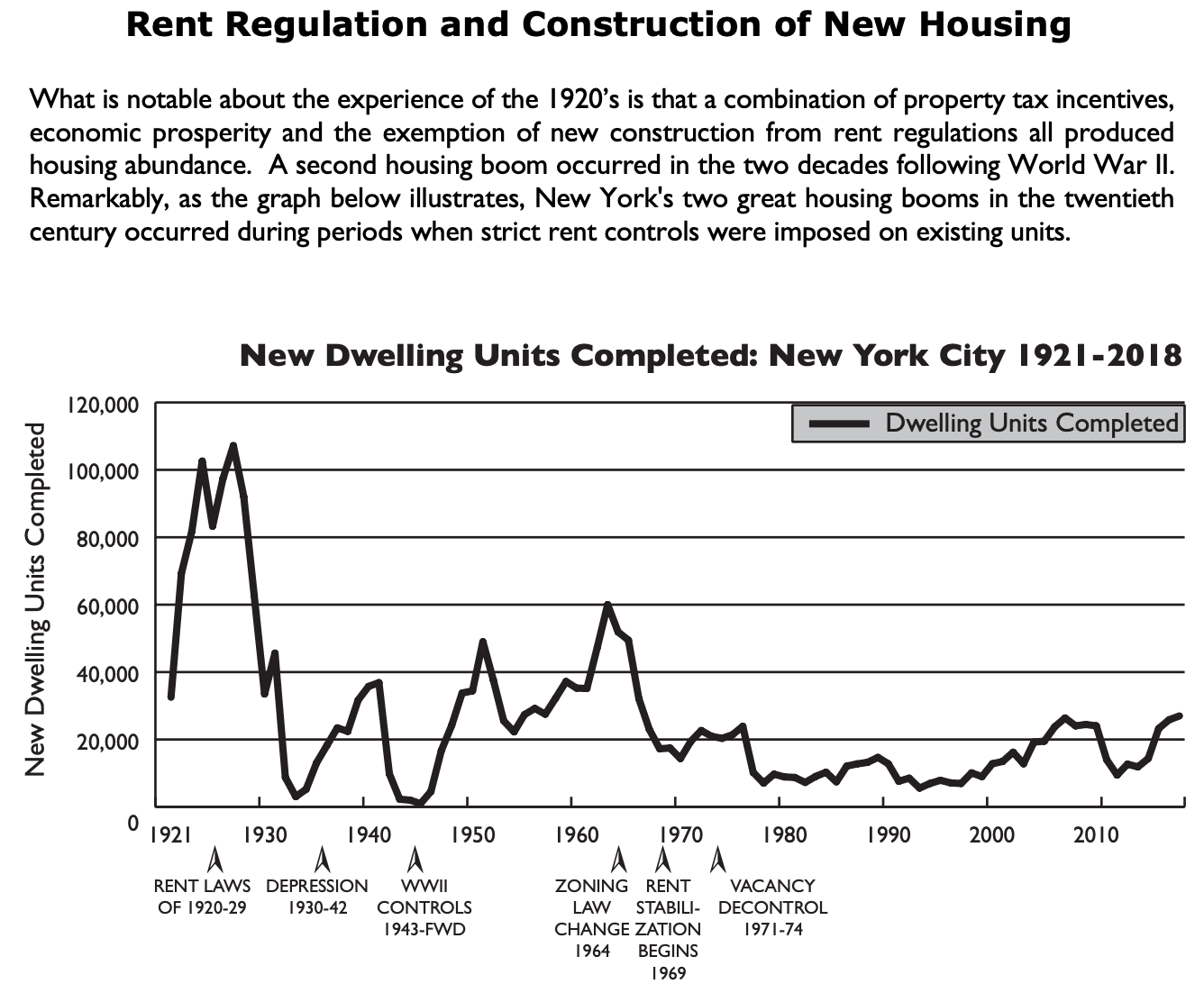

New York imposed its first emergency rent stabilization regime in 1920 following a World War I collapse in home building and a spike in evictions, when vacancy rates fell below one percent. Yet in the ensuing decade, developers built hundreds of thousands of new units—spurred by exemptions from the rent stabilization law and property tax exemptions—and by the end of the decade, New York City’s vacancy rate had risen above 8 percent. The housing emergency was over, and the stabilization law was allowed to expire in 1929. World War II created a similar dynamic: as housing construction plummeted and inflation rose, the federal government imposed a nationwide rent freeze in 1943. Most cities lifted controls by the 1950s, but New York—unlike nearly every other major city—never fully did. Indeed, New York never declared an end to its postwar rental housing emergency. While there was a modest construction rebound in the postwar years, fueled once again by exempting new construction from controls, it wasn’t enough to end the housing emergency. What began as a temporary wartime measure hardened into a permanent system of local regulation: the contours have changed from permanent freezes to stabilized increases, but today fewer than half of New York’s 2.3 million rental units are market-rate.

Under a 1974 law, New York City is legally considered to be in a “housing emergency,” and rent stabilization remains automatically in place, so long as its rental vacancy rate is below 5 percent. That threshold hasn’t been met at any point since 1960, and today the vacancy rate is 1.41 percent, the lowest in decades. New York has been in a state of housing emergency, and under some form of rent control, continuously since 1943. If rent freezes were the key to building political support for abundance, you’d expect the city to be leading the nation in new housing. Instead, after so many decades, it finally managed to pass its first substantive rezoning with last year’s City of Yes program, which will unlock around 80,000 new homes over fifteen years. The city needs an estimated half-a-million homes over ten years to get back to a healthy vacancy rate.

So what does Mamdani propose to end this chronic shortage?

The mayor-elect’s housing plan includes genuinely smart ideas—abolishing parking minimums, modest upzoning, and fast-tracking compliant projects—but also the usual “everything bagel” of affordability, labor, and sustainability requirements that make fewer developments feasible. Those requirements also make it harder, slower, and more expensive to build housing in 2025 than in 1925. Mamdani has courted YIMBYs with talk of changing his mind about “the role of the private market in housing construction” and endorsed a slate of pro-housing ballot measures that passed on election day. But his most specific development priority remains a grand plan to borrow $100 billion for public housing—even as the city faces a $10 billion structural deficit. The new mayor may soon find there isn’t always money in the banana stand.

If Mamdani governs as he campaigned—pursuing new controls without removing old barriers—New York’s housing emergency will simply never end. Rogé Karma calls rent control “a gamble” that might help the city break through its political impasse. But after eighty-two years of taking that gamble, it should be clear that rent control isn’t the way through the impasse; it is the impasse, reinforcing a culture of housing scarcity. The only real path forward is to do what New Yorkers of the 1920s understood instinctively: make it possible to build, at scale and without delay. Mamdani’s charisma gives him a rare chance to make that case—to turn moral energy into actual housing—but expanding rent control without expanding supply would only prolong the affordability crisis he was elected to fix.

Since New York first declared a housing emergency, we’ve eradicated polio, gone to the moon, and invented artificial intelligence—yet the city still can’t figure out how to legalize enough homes. Rent control has always been a symptom of the problem, never its solution. New Yorkers are deluding themselves if they think that this time, it might work for them.

Further Reading

The Revolution’s Happening in New York

One of my favorite songs from Hamilton: An American Musical comes early in Act I, as the Schuyler sisters walk the streets of Manhattan on the eve of the Revolution. They sing, “History is happening in Manhattan and we just happen to be in the greatest city in the world.” The song has stuck with me—not just because it’s catchy, but because it captures a…

Well said. “Housing crisis,” “housing emergency,” and other vague phrases don’t describe a tangible problem or lead to solutions. “Housing shortage” is a much clearer term pointing to a real phenomenon downstream of several social issues, a phenomenon which policy interventions can address

As a newbie housing provider (my preferred pronoun instead of landlord) I can testify that the three headed hydra of rent control- price, just cause eviction, and tenant relocation provides a STRONG disincentive to renting out a portion of my personal residence.

While large landlords have their staff, legal department, investors, and are not going to be living next to who they rent to, owner residents are subject to an onerous set of rules that have made this homeowner decide to NOT rent a unit, the ADU that we just built for our daughter's future.

Instead we are embarking on the lodger route- a housemate that is not eligible for rent control "protections." It's still a perilous path, but we need to bring in income for the doubling of our mortgage AND property tax bill.

There is a carve out in my state and city for owner-residents of single family residences, but our home is a duplex, and even though separately owned as a condo, we are disqualified, and thrown into the same set of rules that control large apartment buildings run by corporations.

This and other stupid zoning rules- if you convert a portion of your home for rental, you cannot restore the original home, because that would constitute "destroying" a rental unit, even if no change to the bedroom count or square footage.

You are correct that rent control laws are popular. I'm sure I voted for these measures before I became subject to their rules. My hope is to expand housing opportunities, by returning some rationality to rent control.