The Problem We Still Live With

Austin Can Plan for a Better Future by Rejecting the Plans of the Past

“[W]e would urge that your City Plan, when adopted, be zealously guarded and closely followed, subject to intelligent adjustments due to changing conditions…and that the improvements be carried out with a real vision of the future with the recognition that the City of Austin is to endure and grow for a long time…”

So implore Koch & Fowler, authors of “A City Plan for Austin, Texas,” a 1928 planning document whose legacy would shape Austin for generations to come. Written at a time when Austin’s population was less than 50,000 and its borders were confined to an area that extended not too far beyond downtown, the Plan lays out a bold, almost utopian vision for a city growing into the future.

Streets would be widened and paved to account for increasing automobile use (Austinites were already complaining about traffic in 1928). Boulevards would be sculpted and lined with trees. Playgrounds and parks would be built within a half-mile walk of every person in the city, in recognition that “proper recreation has for any community a most important relationship to its production, the condition of its people, their well being and prosperity.” A system of street cars would be extended and buses would be coordinated to facilitate growth in the surrounding areas that Austin would inevitably annex. Fire stations would be updated and relocated to reflect the transition from horse-drawn to motorized equipment. Civic spaces and bridges would be built with an eye toward beauty. Views of the gleaming pink dome of the Texas Capitol would be preserved and maximized.

And black Austinites would be shunted into a new “negro district.”

While many of the more utopian aspects of the Plan never came to fruition, the streets were widened, many boulevards and parks were built, views of the Capitol were preserved (though not until 1983)—and the Plan’s most dystopian aspect, the “negro district,” became a real-life nightmare.

Unfortunately, the Plan’s treatment of the city’s black population is strikingly and depressingly reflective of the era’s Jim Crow racism. This historical fact stands in stark contrast to Austin’s contemporary image as a cool, welcoming hub of innovation and culture—an image that emerged despite the city’s past.

But the legacy of 1928 is still very much with us today: zoning and other land-use restrictions first introduced to Austin in the Plan continue to perpetuate the injustices of segregation while driving a widespread housing affordability crisis. This history informs Austin’s present and poses challenging questions for how to plan for its future.

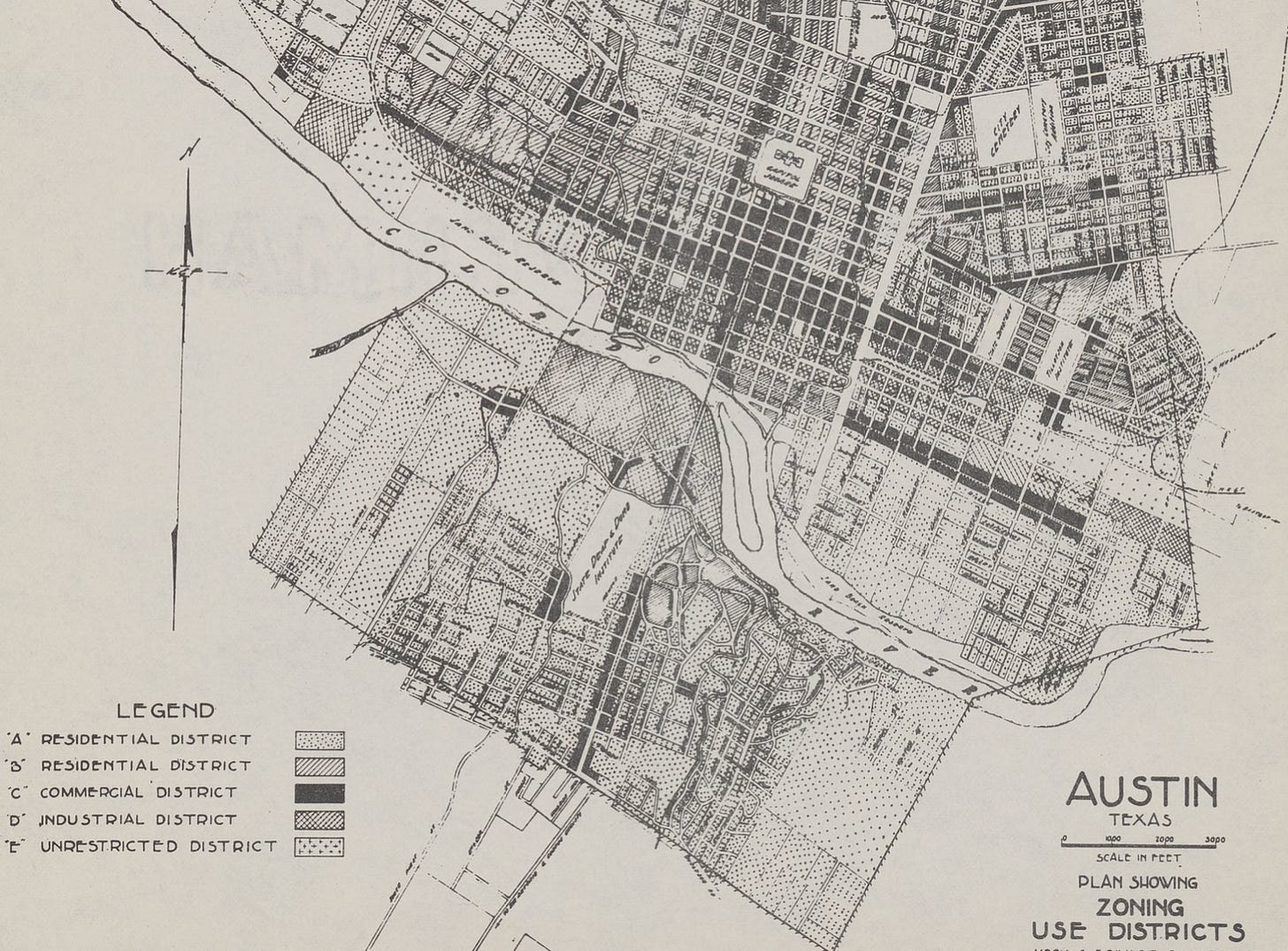

The 1928 Plan does not tiptoe around the issue of racial segregation. Koch & Fowler explicitly link it to zoning, at the time a relatively new practice of segregating land by its “optimal” use, whether residential, commercial, or industrial. The Plan discusses the increasing popularity of zoning ordinances throughout the United States as a “method of safeguarding the property owners” but stresses they “must be based primarily upon the principle of public safety and public health rather than upon any purely aesthetic consideration.” Otherwise, a court might declare a zoning law unconstitutional.

How could an “aesthetic consideration” lead the courts to strike down a law? The word “purely” provides an implicit indication: the phrase is a euphemism for skin color.

Koch & Fowler go on to write, “There has been considerable talk in Austin, as well as other cities, in regard to the race segregation problem. This problem cannot be solved legally under any zoning law known to us at present. Practically all attempts of such have been proven unconstitutional.”

Of course, the “problem” bemoaned by the authors is that the Supreme Court, in its 1917 ruling in Buchanan v. Warley, banned the use of explicit racial zoning. So the authors found another way:

In our studies in Austin we have found that the negroes are present in small numbers, in practically all sections of the city, excepting the area just east of East Avenue and south of the City Cemetery. This area seems to be all negro population. It is our recommendation that the nearest approach to the solution of the race segregation problem will be the recommendation of this district as a negro district; and that all the facilities and conveniences be provided the negroes in this district, as an incentive to draw the negro population to this area. This will eliminate the necessity of duplication of white and black schools, white and black parks, and other duplicate facilities for this area.

If you can’t forcibly remove black people from their homes, you can “incentivize” them by denying them “separate but equal” facilities in predominantly white areas.

I’m sure Koch & Fowler’s ingenuity was lauded by the all-white City Council that eventually took this recommendation to heart—and heartlessly refused education, utility, and other city services to black people living outside of East Austin. Elsewhere, the Plan recommended “improvements” that would involve the removal of “very unsightly and unsanitary shacks inhabited by negroes” along areas slated for parks, roads, and private whites-only developments.

The upshot was that the black population migrated to East Austin by necessity, selling their homes in the more desirable (and more valuable) neighborhoods or abandoning them in the areas that would be seized for development. To add insult to injury, the Plan’s zoning map also designated much of East Austin for noxious industrial uses, while also noting that the presence of City (now “Oakwood”) Cemetery in a residential neighborhood “is not to be desired.”

And all the money Austin saved not having to build separate “duplicate” facilities? Well, the city found even greater savings in inequality. As Richard Rothstein explains in The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America:

Once African Americans had been pushed into the Eastside, municipal services in the neighborhood declined. Streets, for example, were more likely to be unpaved than in other parts of the city; sewers were poorly maintained and often clogged; and bus routes that served the Eastside were suspended during the summer, because the same routes served the University of Texas and were not needed for students when the university was on break.

So much for that utopian vision.

The future unfolded with predictable results. Deprived of the opportunity to build generational wealth elsewhere in Austin, and otherwise oppressed by Jim Crow laws, residents of the “negro district” stayed poorer than white residents. Eventually, the construction in the 1960s of I-35—the so-called “interracial highway”—erected a physical barrier between East Austin and downtown. This only further excluded the area from the rest of the city, even as the civil rights legislation of the same era ended legal racial segregation—perhaps a last-ditch attempt to preserve the racial status quo.

Nevertheless, even decades after racial segregation ended, land values in East Austin remained depressed relative to other neighborhoods adjacent to downtown, and the neighborhood remained largely non-white. That changed as the city’s economy began to rapidly grow in the 1990s, and more Austinites sought housing in the urban core. In the well-established white neighborhoods north, south, and west of downtown, restrictive land use policies kept desirable housing in short supply—and therefore very expensive. So people began to cross the “interracial highway” to buy up cheaper properties in East Austin, often demolishing the original bungalows and erecting so-called “McMansions.”

To the neighborhood’s long-time residents, this new racial integration looked and felt more like gentrification and displacement. As property taxes followed land values up and the area’s black-owned businesses closed down, the black population began to fade away. City-wide, the black population declined relative to the white population—from 12% of the population a few decades ago to under 8% today—and within the bounds of the original negro district, the population is now majority white.

Could this have been avoided?

Unfortunately, gentrification and displacement have been compounded by the zoning and land-use restrictions recommended in the 1928 Plan and adopted by subsequent city councils. These rules—from large minimum residential lot size requirements that incentivize the construction of million-dollar McMansions, to setback and height restrictions that often make it infeasible to build anything other than a “luxury” apartment, to a site plan review process that has transmogrified into a beastly 1,500 steps, thousands of city staff hours, and a year or longer to approve residential developments—remain in place in some form to this day.

These rules restrict the supply of and add tremendous costs to the housing that can be built, putting intense pressure on property values adjacent to downtown—north, south, west, and east—reducing affordability everywhere, reflected in sky-high sale prices and rents and the regular stream of articles lamenting Austin’s loss of its low-cost lifestyle.

While housing affordability is a problem that affects Austinites of all racial backgrounds, especially in recent years, the long arm of segregation extends into the present day. Black Austinites earn only 54% of the median household income earned by white Austinites, which means they are more acutely shut out of the housing market.

In the shadow of Austin’s troubled history of land use, there is some light. After many years of false starts, Austin is finally taking steps to address housing affordability. The City Council has passed resolutions, some of which are now working their way into law, that would allow more and smaller homes to be built on residential lots, dramatically reduce the minimum lot size required to build a home, and reform height and size restrictions. The city is also trying to fix its cumbersome and expensive site plan review process. All of this should help lower housing costs.

Of course, while these reforms should be applauded for taking necessary action in the face of a housing crisis, they cannot undo the legacy of the 1928 Plan—that’s a problem we still live with.

In their conclusion, Koch & Fowler note that the “careful preparation of any city plan, and its adoption by the authorities, does not automatically serve as a panacea for all municipal ills.” Indeed, Austin’s officials should be mindful, as they take a much-needed look at the land development code, of the way that city planning can serve as the source of municipal ills. Zoning rules that seem innocuous by modern standards can still have a pernicious effect on what gets built and who gets to live in it. In Austin’s case, many of those rules are inextricably tied to the segregationist intent of the 1928 Plan, and even if they are no longer explicitly used for those ends, they were created with the goal of keeping certain people out. They succeeded in ways that the 1928 planners could not have dreamed.

Only in rejecting the land-use mistakes of the past can Austin build a better future and live up to its modern-day reputation. The problems those rules cause are policy choices—and we don’t have to live with them.

Such an interesting essay Ryan! Awesome work :)