Trump City

Urban Politics in the Age of The Donald

The ambitious 29-year-old developer scored a coup in 1975 when he optioned 76 acres of prime Manhattan real estate from the bankrupt Penn Central railway—and he had big plans. He would transform the former railyards on the Hudson River and build 30,000 middle-income apartments and a new park, relocating the highway that traversed the site. The neighboring community balked at the scale of the project, so he reduced the number of homes to 14,500, then to 8,000, but the community would not give in. So after three years, he gave up. A subsequent proposal also went off the rails amid fierce opposition and bureaucracy, and so Penn Yards remained abandoned and overgrown.

The story of how the impasse was broken and the railyards became a vibrant residential community tells us a lot about urban politics—and perhaps something about Donald Trump, too.

Trump, of course, was the stymied 29-year-old, but in 1985 he bought the railyards outright and would try again. Amid New York’s real estate boom, Trump had by then made something of a name for himself, becoming “The Donald”—synonymous with a certain 1980s-vintage, big hair, power-suited, gold-plated urban aesthetic. He epitomized what Ada Louise Huxtable described as an era of “rampaging gigantism” where “megalomania is the current style.”

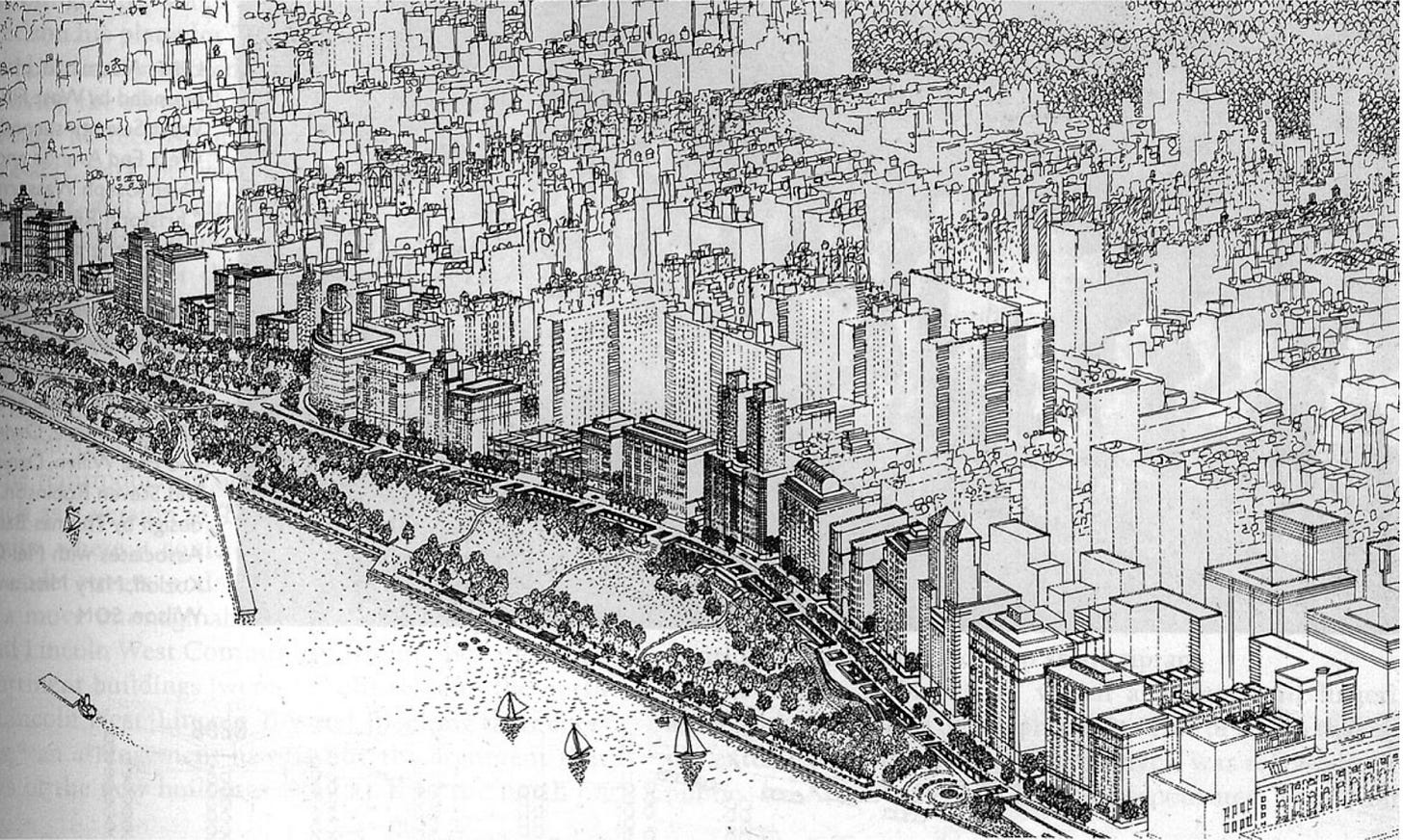

So perhaps it was no surprise when Trump revealed a plan for the railyards that was as bold and braggadocious as himself. Containing 18.5-million square feet, Trump’s “Television City” featured the world’s tallest building, NBC studios, nearly 8,000 luxury apartments, and a private park atop a massive 13-block parking garage and shopping mall. The public would have access to a narrow waterfront promenade beneath the elevated highway. With its monolithic towers-in-the-park and indifference to street life, architecture critic Paul Goldberger wrote that the plan was “antithetical to the elements that make a city truly a city, truly urbane, and not merely a collection of tall buildings.”

Trump, of course, embraced the spirit and style of the age: “Maybe it’s because of my sense of megalomania, but I look at this building as being a true, vital symbol for New York.” He didn’t dispute the criticism that Television City would not be integrated with the Upper West Side. As he told the Miami Herald: “I don’t want to cater to the community immediately surrounding Television City…I want to build my own thing.”

But that’s not how anything gets built in New York.

Steve Robinson’s memoir, Turf War, recounts the story of how the grassroots group he co-founded, Westpride, went head-to-head against Trump—and ended up helping him develop the railyards. The self-described “underdogs” of Westpride included giants of the stage and page like Robert Caro, James Taylor, and Paul Newman. Westpride faced criticism from more radical activists, who called them “Central Park West elitists” and opposed their focus on “rational planning and appropriate development on the West Side.”

Nevertheless, with their well-heeled supporters, Westpride took to the charity circuit and the courts to wage war on what it saw as an irrational and inappropriate development. They argued that the project would block access to the Hudson, threaten neighborhood businesses, and generate “intolerable” traffic and air pollution. For Westpride, the project represented an attack on the Upper West Side’s quality of life, while the Trump Organization saw it differently: “We’re selling sex and dreams. We’re selling a piece of Donald Trump.”

But nobody on the Upper West Side wanted any piece of him.

Trump failed to charm the neighborhood and lost the support of Mayor Ed Koch, whom Ada Louise Huxtable had accused of selling off the city. Koch (“a moron” and “a horrible manager”) struck a deal that kept NBC out of Television City, forcing Trump (“piggy, piggy, piggy”) to go back to the drawing board. Trump replaced TV studios with housing, parks, and offices, but the core elements of the project remained unchanged—except for the name. It would now be called “Trump City.”

Nobody wanted that either. By 1989, Trump City remained unbuilt—and Trump’s mounting business struggles only cast further doubt on the project.

The opposition may have saved him.

While Westpride fought in court, some other nonprofits (the “Civics”) developed a more contextual conceptual master plan that proposed 7.4 million square feet of apartment buildings overlooking the new park and integrated with the existing street grid. The highway would be rerouted beneath the park, an option that would be delayed for decades if the state embarked on a planned $85-million rehabilitation. After the Civics achieved a court victory that effectively ended Trump City, Trump’s office requested a meeting with them.

When Trump saw their plan, dubbed Riverside South, he was effusive: “This is fantastic, brilliant, I love it!” he said, while complaining that his “idiot” architects had been wasting his money. Though a far cry from the 18.5 million square feet he had once envisioned, Trump stayed at the bargaining table and negotiated a compromise plan: he agreed to build 5,700 apartments, television studios, offices, and retail space across 8.3 million square feet, and he’d build and pay for a 23-acre park and donate a right-of-way for the highway relocation.

Trump gushed, “All you folks convinced me to do really what was right….Negotiating with the community groups has been an amazing process—a beautiful process.”

In an unprecedented move, Trump joined the Civics as co-equal partners to create the Riverside South Planning Corporation (RSPC), a nonprofit tasked with overseeing the implementation of the negotiated master plan. The New York Times likened it to “David and Goliath forming a joint venture company.” Trump would pay the organization’s bills, while the Civics would usher the development through the city approval process. As the critic Paul Goldberger knew, even a good plan would still have detractors: “so things go in New York, the city in which saying no is always politically correct.”

Right on cue, State Assemblyman Jerry Nadler and NIMBY activists called it a betrayal, branding Westpride and the other Civics as traitors and sellouts.

The RSPC members negotiated the details and designs of the project and developed drawings to submit for the city’s cumbersome public review process, the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP). They secured state and federal funding to study highway relocation. After Trump submitted the plans to the city in February 1992, the project received certification within three months—a goal that had eluded him for almost five years. ULURP had begun.

Manhattan Borough President Ruth Messinger had “requirements, not recommendations” that included subway upgrades, lower building heights, and affordable housing. Trump agreed and got her sign-off.

The Planning Commission reduced the size, increased the affordable housing requirement, and extracted a $19 million “donation” for transit upgrades. Trump agreed and got the Commission’s unanimous approval.

Next, the City Council’s Land Use Commission asked him to drop the television studios. With no anchor tenant, Trump agreed, and the Commission approved the project 12-2.

The City Council required only that Trump donate $500,000 to community nonprofits. He agreed, and the plan passed 42 to 8. It had taken 17 years from his first attempt, but Penn Yards would be redeveloped into Riverside South. The Civics had delivered.

When Assemblyman Nadler was elected to Congress in 1992, he fought to retain the elevated highway, vowing, “I want to kill Riverside South.” Trump laughed it off, noting that keeping the highway in place would save him a lot of money, insisting “It’s about whether New York gets a great park.” Nadler didn’t kill the project, and the first buildings of Riverside South opened in 2000 with “Trump Place” emblazoned on each facade. It would take twenty more years for the final buildings to open. By then, Trump’s name had been removed and he had long since cashed out.

The elevated West Side Highway continues to cast a shadow and spew pollution over Riverside Park South. When we last lived in Manhattan, we used to walk our dog daily along the park’s undulating riverfront paths as the highway roared overhead, while the entrance to the partially-completed tunnel that would have diverted it underground gaped behind a chain-link fence. Despite the vibrancy of the new neighborhood, a sense of unfinished business and unrealized potential pervades the place.

As Trump returns to the White House on Monday, the story of Riverside South offers insights into how his administration might approach cities and urban policy challenges—and how cities might approach him.

A key lesson is about Trump himself. Facing bankruptcy, Trump was willing to completely abandon his larger-than-life vision for a more grounded victory. Paul Willen, the architect who designed the master plan, said that the “180-degree turnabout he made revealed something about his audacity and his willingness to…go in any direction at any moment.” Trump will turn on a dime so long as he gets credit for a win.

Another is that one must confront political realities as they are, not as one wishes them to be. Had Trump recognized the political realities of the (horribly flawed) ULURP public review process sooner, he might have avoided delays and financial struggles; similarly, Nadler’s petty opposition to highway relocation only harmed his constituents. Urban leaders ought to approach the incoming administration with similar political realities in mind, focusing on collaboration where possible rather than self-defeating “resistance.”

The story also teaches us that constructive community engagement can overcome the Culture of No and deliver a veto-proof consensus and superior results: in this case, a more neighborhood-friendly project that was bolder and better than what the neighborhood envisioned (though, amidst New York’s ongoing housing shortage, one mourns the 30,000 middle-income apartments Trump proposed back in 1975). It takes a durable coalition united by a shared vision to get to “yes.”

In this new administration, cities should embrace the “beautiful process” and seek potential areas of alignment with the administration on shared policy priorities like housing, transportation, and public safety. Democratic mayors like New York Mayor Eric Adams and Washington DC Mayor Muriel Bowser have already met with Trump to discuss how they can collaborate to solve urban problems. Perhaps Congressman Jerry Nadler should revisit his earlier views and schedule a visit to the White House to help deliver on Riverside South’s original vision.

Even he has to realize, for better or worse, we’re all living in Trump City now.

Great article. Thank you for taking the time to write it.

As a resident of NYC then, I remember that project. I mourn how NIMBYism always seeks to cut large scale projects “down to size.” Even if someone didn’t like the details of Trump’s vision, it is “thinking big” that made New York a great city.

As for that particular project, its most horrible manifestation of NIMBYism was Rep. Nadler’s spiteful action to prevent the highway from being put underground, as Trump offered to do. In order to spite Trump all he did was create a permanent eyesore for residents of that neighborhood, as you point out.

As Trump would say, “That is so sad.”

(Incidentally, I am not a Trump supporter, but I do support the right of property developers to decide how to build on their property.)