When “Just One More Lane” Runs Out of Road

Geometry, Politics, and the Limits of the Highway State

As the saying goes, everything’s bigger in Texas—and that includes our road system. With more than 700,000 lane-miles, Texas maintains the largest network in the country, roughly 50 percent larger than that of the next state. The Texas Highway Department, the forerunner to today’s Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT), even started a travel magazine in 1953 to encourage Texans to explore what an awestruck Georgia O’Keeffe described as “the same big wonderful thing that oceans and the highest mountains are.” The magazine was called Texas Highways, and the implication was clear: the way to get around Texas was on its roads.

Now, TxDOT is confronting the possibility that the way Texans have gotten around in the past is not exactly the road to the future.

Part of it is financial. Running the country’s largest road system is expensive: TxDOT projects spending over $43 billion in the next decade just to maintain the existing system, with another $100 billion allocated for expansion. There are also hidden costs: within the Texas Triangle—home to roughly 80 percent of the state’s population—drivers lose an estimated 423 million hours to congestion each year, imposing $11 billion in economic costs. Congestion has continued to rise even as the share of Texans working remotely has more than doubled. Meanwhile, the Texas population is expected to grow 40% by 2050, increasing per-person traffic delays by 200%. All that congestion is deadly: more than 75,000 people have died in crashes since November 7, 2000, the last day without a traffic fatality in the state. While TxDOT itself operates less than 30% of the total lane-miles in the state’s roadway system (the rest are local roads), 64% of all fatal and serious injury crashes occurred on state-owned roads. The department wants to reduce the 4,000 or so annual fatalities to zero by 2050.

Historically, the state has approached the problem of congestion by building more lanes. But by TxDOT’s own admission, the “just one more lane” strategy has reached its limits.

Texas offers a clear empirical test of whether highway expansion can reliably relieve congestion. The state has space, money, and political support to build roads at a scale few others can match, so if congestion, safety, and access could be solved by lane-miles alone, Texas should be the place where that strategy succeeded. Instead, the results have been mixed at best. After TxDOT expanded Houston’s Katy Freeway to 26 lanes, subsequent studies found that travel times during peak periods worsened rather than improved, as increased capacity was quickly absorbed by additional driving. If lane expansion were going to solve congestion anywhere, it would have solved it here. Instead, Texas ranks near the bottom of U.S. states in measures of urban congestion.

At root, the congestion problem is a connection problem: Texas cities have grown rapidly and they’ve grown outward, with jobs dispersed across metro regions; for the most part, the only way to get around is via those 700,000 miles of roadways. That problem is shaped largely by geometry: automobiles consume large amounts of space relative to the number of people they carry. A typical city bus can carry forty passengers while occupying roughly twice the length of a Ford F-150—often occupied by a single driver. If those same forty people travel separately by car, their vehicles would consume 20x the road space even before accounting for safe following distances. Scale that difference across tens of thousands of vehicles moving through the same constrained corridors, and congestion is no longer a failure of planning or enforcement but a predictable outcome of space constraints.

And in densely built up urban areas, that space is very constrained. To facilitate an expansion of Interstate 35 through Central Austin, TxDOT had to purchase (via eminent domain) more than 100 homes and commercial properties, seizing 54 acres of valuable land that will fall off city tax rolls as it is steamrolled into additional lane-miles. The project reflects the geometry problem once again: cars take up a lot of space, and expanding urban highways means taking space that is already occupied by higher-value uses. In dense areas, that’s an increasingly expensive proposition.

So it’s noteworthy that this highway-first state is acknowledging that these constraints require new approaches to address Texas’s future transportation needs.

Indeed, late last year, TxDOT published its draft Statewide Multimodal Transit Plan (SMTP), the first of its kind in Texas.1 While that alone is notable, what makes it groundbreaking is its focus on transit alternatives as a necessary part of solving the congestion problem. That the report arrives as TxDOT is in the midst of multibillion-dollar highway expansion projects in urban areas is a reflection of the problem: the state remains deeply committed to highway construction, even as its own analysis shows that widening alone is unlikely to deliver its long-term transportation and safety goals.

TxDOT cites demographic shifts as putting additional pressure on the road-dominant model. The population of seniors is projected to nearly double by 2050, increasing demand for alternatives to driving. The younger cohorts of Millennials and Gen-Zers—rather than ruining everything—express greater interest in and preferences for non-automobile modes. Meanwhile, the state’s growing majority-minority population tends to drive less and use transit more in urban areas. At the same time, many households are increasingly cost-burdened by housing and transportation combined.

Texas already has 77 transit agencies, which together carried nearly 230 million passengers over 252 million service miles in 2024, nearly all of it funded locally. Yet much of this service operates in mixed traffic, limiting frequency, reliability, and capacity. The SMTP argues that many of transit’s shortcomings stem less from missing infrastructure than from weak service, and that higher-quality transit with priority treatment—along with better coordination across providers—is necessary if transit is to function effectively at scale. TxDOT also acknowledges that better communication is needed to overcome misconceptions about transit.

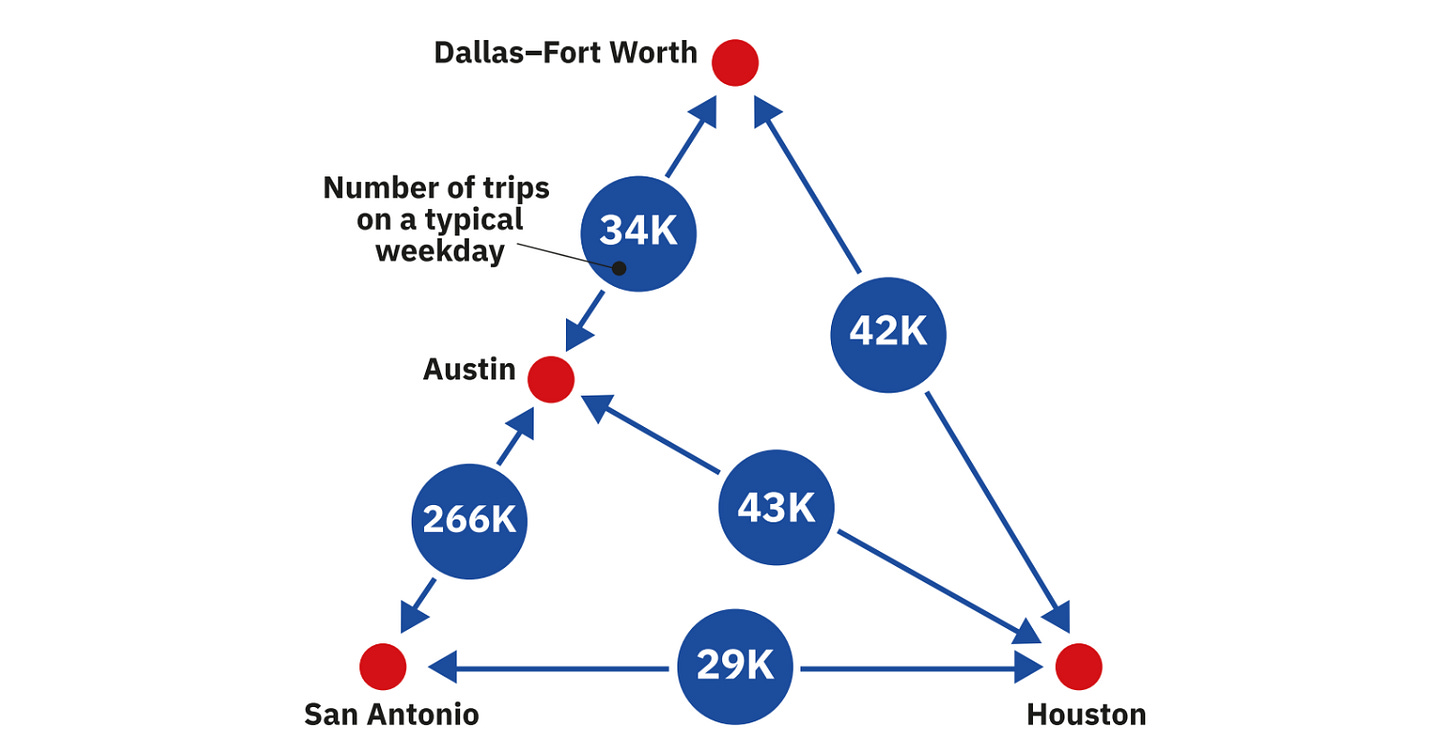

The big opportunities for the state are in intercity transit between the various nodes of the Texas Triangle, where TxDOT projects total Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) will increase by more than 50% by 2050. Today, drivers make more than 40,000 daily trips between Houston and Dallas-Fort Worth, a 3.5-hour drive, and Houston and Austin, a 2.5-hour drive. Strikingly, Austinites and San Antonians make more than 266,000 daily trips along the 90-minute Interstate 35 corridor connecting the two cities. This corridor represents one of the highest-leverage opportunities for improving regional connectivity, and both TxDOT and Travis County are studying the feasibility of a rail connection between the two cities.

TxDOT also opens the door to other transportation providers. The SMTP highlights the role of Amtrak, which already provides passenger rail service across the state (for a mere 7.5-hour ride between San Antonio and Dallas), as well as public-private partnerships that have created bus-oriented transit centers across Texas. They also flag Brightline—a privately owned intercity rail line between Orlando and Miami—as a potential model. Meanwhile, Texas Central, a private initiative to build a high-speed rail link between Houston and Dallas has struggled to gain traction. The plan suggests that autonomous vehicles will undoubtedly be a part of the state’s transportation future but stops short of spelling out policy proposals.

While TxDOT acknowledges both the high costs of the congestion problem and the potential economic benefits of transit alternatives, the SMTP is devastatingly realistic about the challenge:

“No funding source exists for delivering a statewide transit network in Texas.”

Under the Texas Constitution, nearly all state transportation dollars are dedicated to roads, leaving transit largely dependent on federal, local, or other sources. Meanwhile, the state legislature’s recent interest in alternative transportation modes has been in trying to defund local transit. So it’s no surprise that Texas’s transportation system remains overwhelmingly road-dominant. Statewide, total VMT reached more than 300 billion in 2023—more than 1,000 times the service miles traveled by the state’s transit agencies. On a per-capita basis, Texans log roughly 10,000 vehicle miles of travel per year, while transit agencies collectively provide about eight service miles per resident.

If Texas is Car Country, it’s by design.

While it seems unlikely that Texas as a whole is ready to embrace transit, TxDOT has done perhaps the hardest work of all: admitting that we have a problem, and acknowledging that the road to recovery will not be paved with one more lane. The significance of the SMTP is not that TxDOT has suddenly embraced transit, or that highways are about to be abandoned. It’s that the state’s own transportation agency, based on its own data, has concluded that roads alone cannot deliver the transportation outcomes Texans want. If the future of transportation in Texas is multimodal, it’s not because TxDOT has changed its values but because it has recognized real-world constraints. Congestion, at root, is a geometry problem. Solving it, however, is a political one.

Thanks to Jon Boyd, author of the What Are Streets For Newsletter, for encouraging me to write about this.

The only way to get more rail is for the Lege to change the state constitution to allow TxDot to use highway dollars. If they would only do that I’d be ecstatic. I’d love to be able to take a high speed train to San Antonio and back, for a Spurs game. The twice a year that I see them here is great, but I’d love more!

This is a really good analysis. The route to better transpiration in Texas is steel wheel on steel rail. It is more fuel efficient, land efficient, has less noise and air pollution and far more comfortable.