Austin's Migrant Crisis

People: the Cause of and Solution to All of Our Problems

Once upon a time, everything in Austin was idyllic—perfect, even. The city flowed: limpid spring-fed waters rolled through Town Lake, traffic cruised past a modest skyline punctuated by the pink dome of the state capitol, and cheap booze, live music, and ragtag revelers spilled from dive bars onto open streets. Life was laid-back and low-cost in this lazy river of a city.

And then it all went down the drain.

Californian tech bros drove in on their Teslas, drove up the price of housing, drove out longtime residents, choked up the highways, and dried up the aquifers. The Live Music Capital of the World was corporatized, sold off by the Chamber-of-Commerce City Hall to the highest bidders for a bunch of Bitcoin, and rebranded as The Joe Rogan and Elon Musk California Adventure Experience™. Rapacious developers tore down downtown and rebuilt it with soulless skyscrapers for short-term rentals. All the good places, the stuff that kept Austin weird—can we use that word anymore?—they were all replaced by Hermès and Soho House, chain-store luxuries for the post-IPO Uber-rich.

With their intermittent soylent cleanse diets, they’re probably not eating people’s pets—but can you really trust them?

The trampling of Old Austin by newcomers has become something of a trope in literary takedowns of the city. Last year, The New Yorker asserted that Austin has become a “turbocharged tech megalopolis,” while The Atlantic recently claimed that Joe Rogan has “remade” the city into “a haven for manosphere influencers, just-asking-questions tech bros, and other ‘free thinkers’ who happen to all think alike”—quite unlike the free thinkers reading The New Yorker and The Atlantic, I imagine. Meanwhile, the forthcoming Lost in Austin, of which I read an advance copy, gives the trope a book-length treatment.

Whatever the word count, the story is the same: explosive growth detonated over Austin and things are not alright, alright, alright.

But what if the trope is all wrong?

I’ve never actually heard anybody say “Don’t California My Texas,” but I’ve heard some version of the trope at least a hundred times at City Hall public hearings. “Growth” destroyed Austin’s familiar form and weird character, replacing it with bland buildings and bad hombres. If only we could keep the city as it physically was, we could somehow prevent further change. The only way to stop growth, then, is to stop the people: y’all ain’t welcome here!

What’s interesting about this view is that it recognizes that people are inherently productive, that in fact new workers and new consumers, with new ideas and new technologies, add up to a whole greater than the sum of its parts. The grain of truth in the anti-growth thesis is that growth does bring change, not all of it good. All else equal, rapid growth can lead to higher resource consumption, more traffic, and an increase in the cost of living, which can cause displacement. But this view assumes economic growth is zero-sum, ignoring the possibility that there are other factors that determine how broadly the benefits of growth will be shared.

Because the numbers suggest that growth has been, on the whole, good for Austin and good for Austinites.

The data backs this up. The Austin metro area leads the state not only in population growth, but in GDP and employment growth, too. Austinites have the highest incomes in Texas, while the rate of poverty has fallen to 9.5%, below both the statewide (13.7%) and national (11.1%) rates. Growth has raised the standard of living in the Austin metro area.

And it’s not just the economic benefits. The greater variety of people has meant the city can cater to a greater variety of interests. Today’s Austin has mosques and synagogues and Sikh gurdwaras, restaurants serving Caribbean and Indian and Vietnamese fare, CrossFit boxes and Barry’s Bootcamps and Lagree studios, music venues playing alt-country and indie rock and classic jazz. And you can still get cheap beer and Tex-Mex.

But by 2022, Austin had become the least affordable housing market in Texas. The Austin growth machine made the city a highly desirable place to live—but the city’s Orwellian land development code, last rewritten in 1984, made sure there weren’t enough places for people to live and priced out the weirdos. Rules like minimum lot size requirements, single-family zoning, and height restrictions limited densification in the urban core and suppressed the construction of some 82,000 homes. Thanks to the work of local advocates and a pro-housing City Council, Austin has recently enacted major reforms that will make it easier to build a wider variety of homes, easing displacement pressure.

But critics argue that none of these changes would have been necessary if not for the influx of new residents.

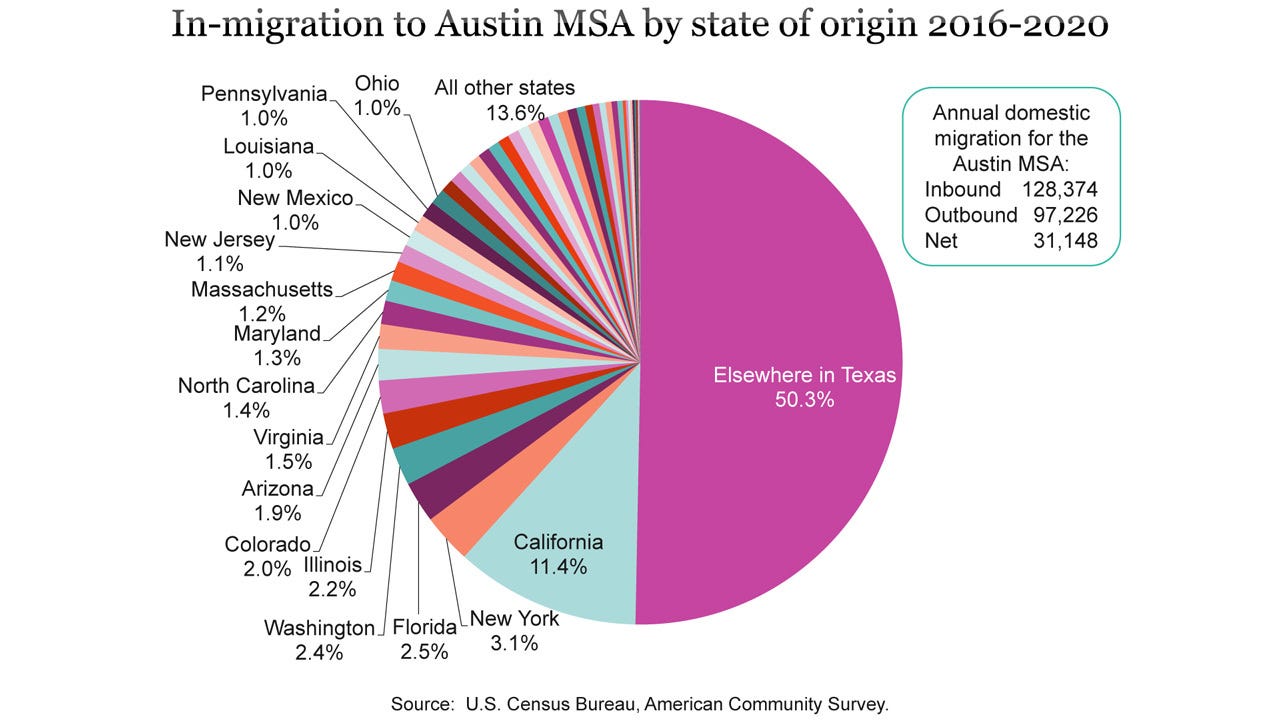

No doubt, Austin has grown quite a lot from a distant outpost on the frontier to the modern metropolis it’s become today, with the population doubling every 20 to 25 years. Most of Austin’s population growth has been from domestic migration—people moving from within the United States—and for the 10 years leading to 2020, 60% of Austin’s average annual population change was driven by other Americans moving here. Domestic migration reached nearly 75% in 2021, before returning to the long-term average in 2022 and slowing further in 2023. But people still want to live here.

For some, we’re still suffering from a migrant crisis.

Lured by high-paying jobs, the migrants descended on Austin and outbid locals for scarce housing, driving up home prices and rents to record highs in 2022. To make matters worse, all this excess demand was manufactured at taxpayer expense, through corporate giveaways that encouraged companies to—gasp!—create those high-paying jobs here in Austin.

That’s the story, anyway. No doubt, Austin and Texas have wooed companies to relocate headquarters or build projects here with juicy tax incentives. But research suggests that 85% to 90% of these projects would have happened anyway—which indicates that while the merits of such deals may be debatable, the idea that we can turn off the growth machine is not. The presence of a world-class research university, no state income taxes, relative affordability, a hospitable business climate, a seasonally hospitable environmental climate, and a vibrant culture seem likely to have something to do with why people want to be here. Blame the founders of the Republic of Texas, the drafters of the state constitution, Mother Nature, or God Almighty for that.

Instead, we’ve blamed the migrants.

I get it. When we see people with weird eating habits and religious practices, who look and think differently than we do, it’s an entirely human response to fear The Other and cast blame when things go wrong, even if “wrong” just means “differently.” And Californians, with their yoga and crypto and avocado toast, with their permatans and vocal fries and overpriced bone broth—they’ve elevated weirdness to another level. Fish tacos instead of breakfast tacos?—that’s not our kind of weird!

But…these California migrants haven’t quite California-ed our Texas.

While California has sent a large number of people to Austin over the years, there’s one state that’s sent five times as many folks, one state that deserves to have all the blame for ruining Austin placed at its cowboy-boot-covered feet.

I’m talking, of course, about Texas.

Texans have Texassed my Texas.

We have met the enemy and he is us. It turns out it is people who are responsible for Austin’s change; it’s just not the ones we’d like to blame. Stasis may have been Old Austin’s preference, but it wasn’t working for all of Austin—for folks from Austin, Elsewhere, Texas, or California alike. We’ve had to make some policy changes to ensure that, going forward, “y’all” really does mean “all.” The city has to evolve, to change its old ways of thinking to remain vibrant and alive in the future. There’s more to do yet.

The migrants are coming. I suppose we could build a wall around Austin and wave “Mass Deportation Now” signs at rallies, but the migrants want to be here, and I’m sure they’ll find a way in (straight down I-35 from Dallas). Who can really blame them for trying? Well, we know who—but blame is not helping us find solutions that actually address the challenges that come with growth. When people come together freely, they create value. Surely, we can solve more problems with a welcome mat than a fly swatter.

Austin, Texas, USA—it’s big enough for all of us, and better off because we’re all here.

The quickest way to California a Texas city is to adopt an anti-growth agenda. I've seen this play before--in Los Angeles, in the 1980s, where becoming New York was the great fear.

I moved to Austin in 1982, and everyone complained then that the Austin had been destroyed by newcomers (me). I kid you not. And they were right in a sense, it was very different from what it had been in the the '60s and 70s. But I loved it and thought I would never leave. In 2002, when growth really seemed overwhelming even to me, I taught a course at UT on visualizing Austin change through time, using GIS and other visualization techniques. Turns out Austin had been growing by leaps and bounds throughout the 20th century. Looking at the results today, what seemed like cancerous growth by 2002 looks so tiny compared with the current Austin region. Bottom line: successful cities grow, and many people mourn for what's gone, similar to how we mourn for lost youth. Maybe since we can't bring back our youth, we try to keep our community from changing. But that's simply not healthy for younger current or future residents. PS - I moved to Boston in 2006 for family reasons, and now am embedded in similar "Boston is ruined". battles here. Fran Leibowitz's "pretend it's a city" is my new mantra. PPS - highly recommend Billy Lee Brammer's The Gay Place (1961) for a look at Austin of the 1950s. Enjoy the nostalgia but don't base your planning and development policies on it.