Too Much Yard in My Backyard

From New York to Austin, Minimum Lot Sizes Don’t Make a Lot of Sense

Less than 10 feet across at its widest point, 75 ½ Bedford Street in New York City’s West Village is considered the narrowest home in the city. Like the Hogwarts Express Platform 9 ¾ at London’s King Cross, the house manages to magically wedge 999 square feet of living space onto a sliver of land where it seems no house should fit at all. Yet, three floors and a basement occupy less than one half of its 720-square foot lot, with room for a rear courtyard. This enchanting if eensy spot has been home to the poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, anthropologist Margaret Mead, and actors Cary Grant and John Barrymore. Last year it sold for $3.41 million—a bargain compared to the much larger neighboring townhouse at 75 Bedford St, which last sold for a cool $10.9 million.

Today, under New York City’s current zoning rules, both houses would be illegal to build.1

Since 1961, New York City has imposed a minimum lot size requirement of 1,700 sq. ft. in this zoning district, leaving 75 ½ Bedford about 1,000 sq. ft. short, while its neighbor is just shy by 20 sq. ft. The most beloved, often historic neighborhoods in many cities were generally built before these lot sizes were standardized, meaning most of what we love we could not build today. But there are some parts of New York City where the minimum lot size is 9,500 sq. ft., forcing a suburban standard of development that prioritizes backyards over homes, meaning the city cannot build what it needs today.

For modern municipal zoning, minimum lot size requirements are the American way.

Starting in the 1920s, municipalities began to impose requirements dictating the amount of land required to build a single-family home. An early adopter, Austin introduced minimum lot sizes in 1931, instituting a 3,000 sq. ft. requirement as part of the city’s first zoning code, which was itself a response to its segregationist 1928 Master Plan. While zoning has its roots in racial segregation, Charles Gardner at the Mercatus Center argues that “exclusionary motives behind minimum lot sizes were both racial and fiscal” (emphasis added). Minimum lot size regulations really gained traction in the years after World War II, and

…reflected a fear that the young families of the baby boom era, in search of modest starter homes, would fail to pay sufficient property tax to account for the cost of educating their growing families. A minimum lot size, by setting a floor for land costs, was intended to slow, if not exclude entirely, the entry of such families, particularly in localities in which the bulk of municipal revenue was derived from residential property tax.

Of course, those “young families of the baby boom era” were often being started by veterans returning home from the war. In thanks for their service, the cities of our grateful nation deployed minimum lot size requirements on the home front to kill starter homes for the Greatest Generation.

Not to be outdone, Austin’s leaders increased the lot size again in 1946 to its current 5,750 sq. ft., presumably after asking, “Why be only racist when you can be classist, to boot?” It’s at least not as bad as suburban Connecticut, where in more than 80% of the state you need no less than an acre of land (43,560 sq. ft.) to build a house.

Pointedly, large minimum lot sizes raise the entry point for homeownership everywhere. If the original goal of these regulations was to kill starter homes, today that victory is complete.

The math is simple: the more dirt you need to build a house, the more expensive the total cost of that house will be. Even New York City shows that a smaller house on a smaller lot has a smaller price—albeit, 75 ½ Bedford Street may be a starter home for multimillionaires. But the relationship still holds: where land is expensive, large lot size requirements force would-be homebuyers to pay, literally, for a lot of dirt that they don’t need and possibly can’t afford, regardless of the size of the home.

Yards don’t house people, yet minimum lot size regulations mandate that huge swathes of our housing-crunched cities remain devoted to land that cannot be used for homes.

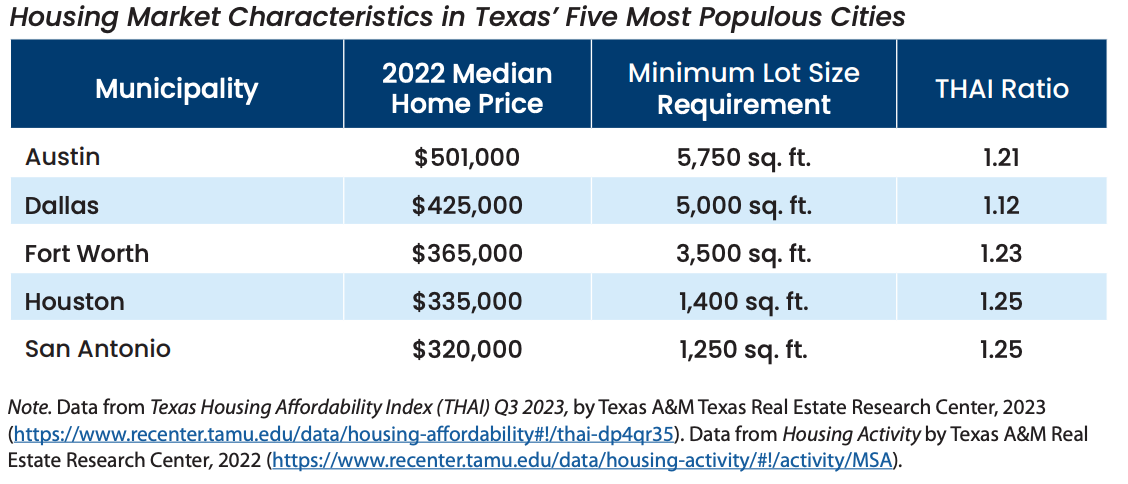

Recent research from the Texas Public Policy Foundation (TPPF) shows a direct correlation between lot sizes and home prices in the five largest municipalities of the Lone Star State. Austin leads the five metros with both its large minimum lot size and $500,000 median home price—not as expensive as New York, but pricey for Texas, especially when compared to San Antonio or Houston.

Houston, which despite having twice the population of Austin has managed to keep home prices 33% cheaper, slashed its lot size regulations in the city center from 5,000 to 1,400 sq. ft. in 1998. Over the past twenty-plus years, it has seen a building boom of small-lot townhouses that has allowed it to remain perhaps the most affordable big city in America. Its policies have both kept entry-level homeownership within reach of middle-class Houstonians and reduced gentrification and displacement in historically marginalized communities.

Austin’s current leaders have seen the errors of their predecessors’ ways, and if all goes well, City Council will shrink the 5,750 sq. ft. minimum lot size requirement tomorrow (May 16, 2024). While we don’t quite yet know what the final number will be, insiders expect it to land somewhere between 1,500 and 2,000 sq. ft.—a huge reduction that, in concert with other reforms undertaken by this Council, will help improve affordability in Austin, and perhaps pave the way to eventual elimination.

Minimum lot size requirements have contributed to making housing unaffordable while perpetuating a sorry legacy of bigotry. Keeping them intact doesn’t make a lot of sense morally or economically—cities ought to dispense with them entirely.

Technically, these sites could in theory be redeveloped today, but they couldn’t be built new.

Great piece Ryan. This is just another reminder of the negative effects of overzealous zoning regulations. Essentially, we can think of zoning regulations as a subtle means of transferring wealth from those who own property to those who do not.

Local boards and city governments become captured by landowners/homeowners who have every incentive to design the rules to inflate the value of their properties. This is not optimal for a number of reasons, it exacerbates the cost of housing, widens wealth inequality, and weakens our ability to take advantage of the scaling benefits that cities provide: https://www.lianeon.org/p/let-a-thousand-skyscrapers-bloom

Keep giving us examples, I am sure they are endless.

You missed the obvious, and epic, pun: "Baby Got Back(Yard)"