Desegregate Connecticut

How Exclusionary Zoning Made Housing Unaffordable in the Constitution State

In 2000, my hometown of Wallingford had the dubious distinction of being the only one of Connecticut’s 169 towns and cities not to fully close its municipal doors on Martin Luther King Day. What began as a labor dispute over the holiday in this town of 44,000 people morphed into a national racial flashpoint, drawing marches by the Ku Klux Klan and Jesse Jackson. The turmoil even attracted the attention of Matthew Hale, a white supremacist whose speech at the public library sparked a riot. State lawmakers eventually intervened with a bill that mandated the closure of all municipal offices on the holiday, but The New York Times’s characterization of Wallingford as “a town known for its history of racial conflict” still stung. The MLK Day dispute aside, the awkward reality was that Wallingford was 94% white and only 1% black.

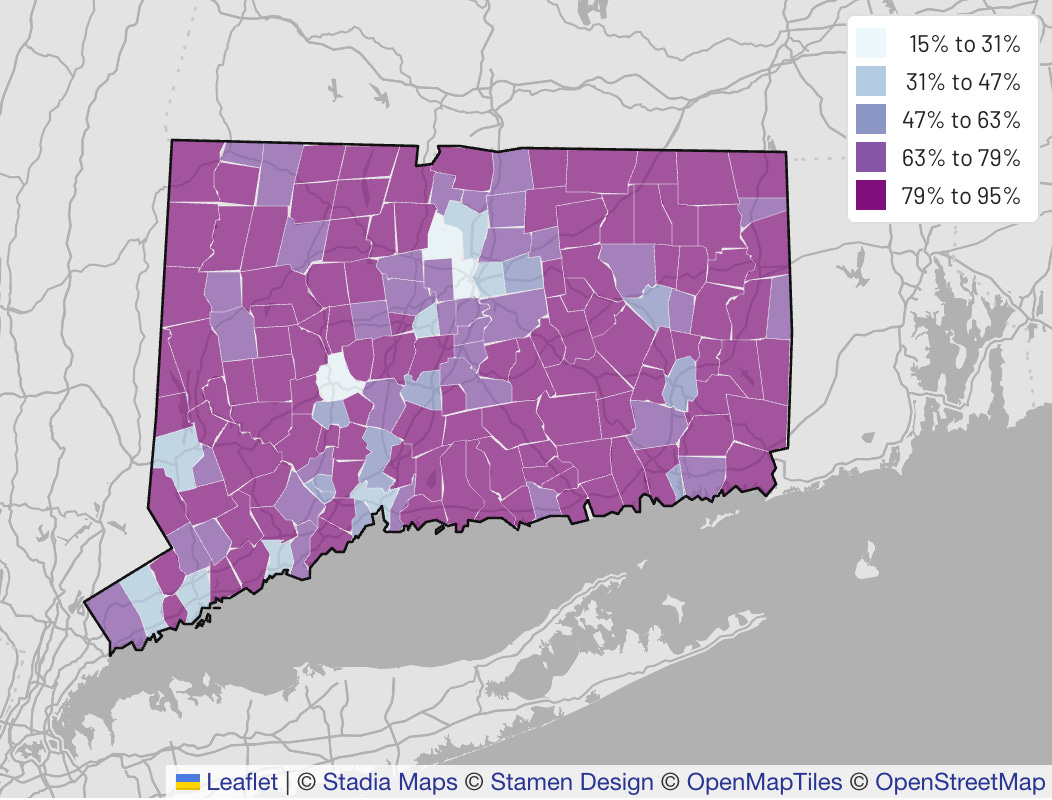

Wallingford was unusual in its notoriety, but not in its demographics. Today, the state population as a whole is 64% white and 10% black, but those totals obscure the fact that the black population is largely concentrated in New Haven, Hartford, and Waterbury—cities where the poverty rate is 20 to 27%, compared to a state average of 10%.

The map reveals a pattern of de facto segregation—one that made the charges against my hometown stick. But what caused it?

I spent much of the past week in New Haven, Connecticut, attending YIMBYtown, a conference of pro-housing advocates where attendees explored such questions. This year’s conference was hosted by DesegregateCT, a coalition of advocates and nonprofits that argues the persistent pattern of segregation that typifies modern Connecticut stems from land-use and zoning choices. They would know: DesegregateCT itself is a project of the Regional Plan Association, whose 1929 highway proposal inspired many of the infrastructure projects Robert Moses built with such devastating impact on lower-income, non-white communities. The RPA’s goal was to improve regional transportation, but the history underscores how planning institutions shaped both the region’s landscape and who was included within it.

That broader story of how exclusion happened in the North is well captured by Richard Rothstein. As he explains in The Color of Law, while the American South unapologetically enforced explicit racial segregation, Northern states used housing and land use policies instead. The federal government reinforced these patterns through redlining and mortgage subsidies that favored whites-only suburbs, while urban renewal projects in cities like New Haven bulldozed entire communities. Although the Supreme Court had struck down explicit racial zoning, land use and transportation policy still produced de facto segregation that kept lower-income, non-white people out of suburbanizing areas.

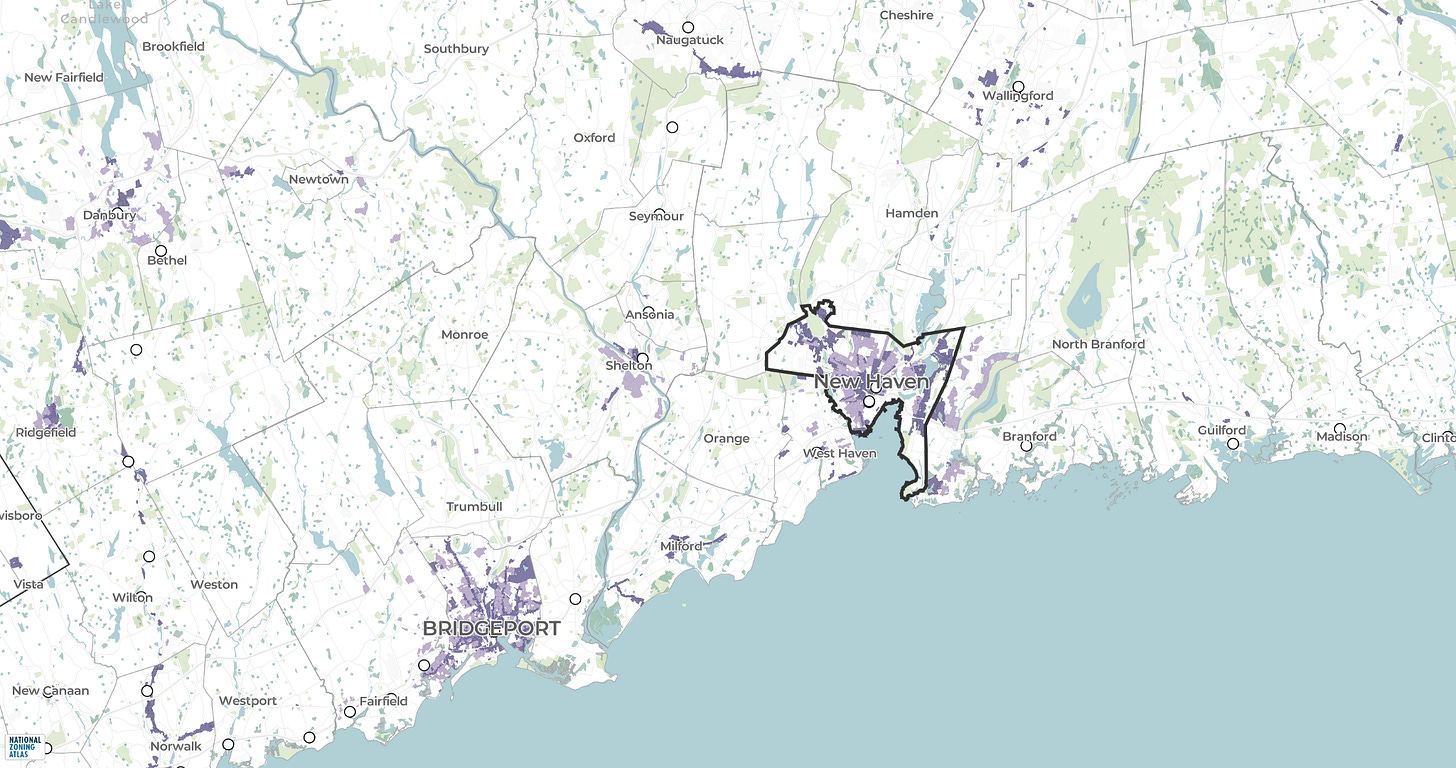

In Connecticut, minimum lot size requirements were among the most effective tools of segregation. Some 80% of the state’s residential land is zoned for a minimum lot size of one acre per home—“almost the size of a football field,” as Sara Bronin puts it in her new book, Key to the City. Bronin—who is also a founder of DesegregateCT—writes that researchers have “found that if Connecticut’s lot sizes were reduced by half, the number of smaller and less expensive homes would increase, and more racial minorities would be able to afford housing.”

Lot sizes were only part of the story. Connecticut’s zoning regimes also worked to “protect” single-family homes from other housing types. That logic still dominates today: while it’s legal to build duplexes on more than a quarter of residential land in the state, a bevy of extra requirements and procedural hurdles has stymied their development, and today they represent only 8% of the state’s building stock. Meanwhile, only 2% of residential land is zoned for by-right multifamily apartments, while single-family homes are allowed without special permission across 91% of Connecticut.

The result of these policies was that large-lot, single-family homes became the dominant form of housing in Connecticut’s suburbs. Shut out of the mortgage market by redlining, black people and other minorities were largely excluded from participating in the postwar homeownership boom and amassing the generational wealth that lifted others. The result is today’s persistent racial wealth and income gaps.

Homeownership rates in Connecticut reveal the gap: 82% of white households own versus only 51% of black households. In the Northeast, white median wealth is about $268k versus $13k for black households—barely a nickel for every dollar of white wealth.

Income and housing costs deepen the divide. White median income is about $95k versus $54k for black households. With nearly half of renters cost-burdened (paying 30% or more of income toward rent) and a quarter severely so (≥50%), it’s no surprise that black residents are three times more likely than whites to live in poverty.

These disparities are exactly what DesegregateCT tried to tackle this past legislative session.

The coalition worked with lawmakers to pass House Bill 5002, an omnibus housing bill that sought to tackle affordability and homelessness with zoning reforms, tenant protections, and new housing programs. The state House of Representatives approved the bill in an 84–67 vote, while the state Senate followed 20–15. Every Republican opposed the bill, joined by a handful of Democrats.

Opponents of HB 5002 framed the bill as a one-size-fits-all approach that would undermine local control. State Republicans claimed that the bill “forces density from the top down, with little concern for infrastructure, public input, safety, or community character.” Democratic Governor Ned Lamont vetoed the bill under pressure—and was not invited to YIMBYtown as a result. Lawmakers and advocates are now lobbying the governor to call a special session to take up the bill again next month.

Blaming the HB 5002’s failure solely on racism misses the mark. One problem is that the bill may have been weighed down by its size: bundling many reforms together made it an easy target for opposition, or perhaps too much for those who may have supported a more moderate slate of reforms. Meanwhile, framing the issue in moral and racial terms brought clarity but not consensus—provocation can alienate as well as inspire. By contrast, state-led housing reforms from California to Texas have all passed with bipartisan support.

Today, Connecticut’s suburbs are more diverse than they were 25 years ago—including Wallingford, which is now only 80% white. Since 2010, nearly every Connecticut town has seen rising Hispanic and Asian populations, even as black residents remain largely concentrated in the cities.

Yet resistance to housing reform remains entrenched. Connecticut ranks 49th in new housing construction and has the lowest vacancy rate in the country. Homelessness is rising, inequality is among the highest in the nation, and housing costs keep climbing. The state’s population has grown by only 1% over the past 25 years. In Wallingford, my hometown’s population has barely budged, a reminder that exclusionary policies don’t just limit who gets in—they limit growth itself.

What will finally move Connecticut to build? Appeals to history or moral clarity reach only so far. The pressure point is more likely to be something that everyone—including those in the suburbs—eventually feels: the lack of affordability. It’s the job of advocates and policymakers to draw the line between the high cost of housing and Connecticut’s ossified land use regimes. Legalizing more housing is good for many reasons—from strengthening transit and local budgets to ending entrenched patterns of segregation—but most of all, it’s the only way to build the homes Connecticut needs.

Perhaps, when it comes to zoning codes, it’s time to deregulate Connecticut.

Great article. Writing from Massachusetts, I fully expect future analysts to realize with horror how our energy efficiency building code and other well-intentioned rules exacerbated segregation here by driving building prices up. All for meager reductions in pollution or emissions (if that) because we're merely displacing the poor.

Any thoughts on CMDA? They seem to be doing some interesting TOD work with municipalities, of course it's all opt-in, and I'm not sure any of their projects are far enough along to properly assess.