Manhattanize Manhattan!

New York City Has Plenty of Room to Grow Up

In June 1957, my grandparents got married and moved from New Haven to New York City. My grandmother worked as a nurse at what is today Memorial Sloan-Kettering on the Upper East Side. The hospital provided workforce housing nearby, which made it possible for them to afford New York on one income while my grandfather chased his dream of becoming an actor. He landed small parts in Village playhouses and even talked his way into Mike Todd’s blowout at the old Madison Square Garden—a 1957 TV “spectacular” he hosted with Elizabeth Taylor that Walter Cronkite later panned as an “essay on empty extravagance.” That year, West Side Story debuted, even as Robert Moses cleared the San Juan Hill “slum” where it took place to make way for Lincoln Center. Right before my grandparents left the city in 1958, their first of five sons on the way, Jane Jacobs would publish her seminal essay, “Downtown is for People.”

It was during this time that New York City’s leaders decided that downtown had enough people already.

Where people like my grandparents saw vibrant urban life, the midcentury planners saw chaos and congestion—something to be reined in and tamed, not nurtured and cultivated. So they passed the 1961 Zoning Resolution. Assuming car dominance was inevitable, they mandated parking minimums for developments of all sizes and encouraged towers-in-the-park or on plazas, thanks to a new regulatory tool that let developers build bulkier in exchange for “privately owned public spaces.” And they slashed allowable density across much of the city—including large swaths of Manhattan—protecting homeowners in low-density areas who feared “tenement” encroachment.

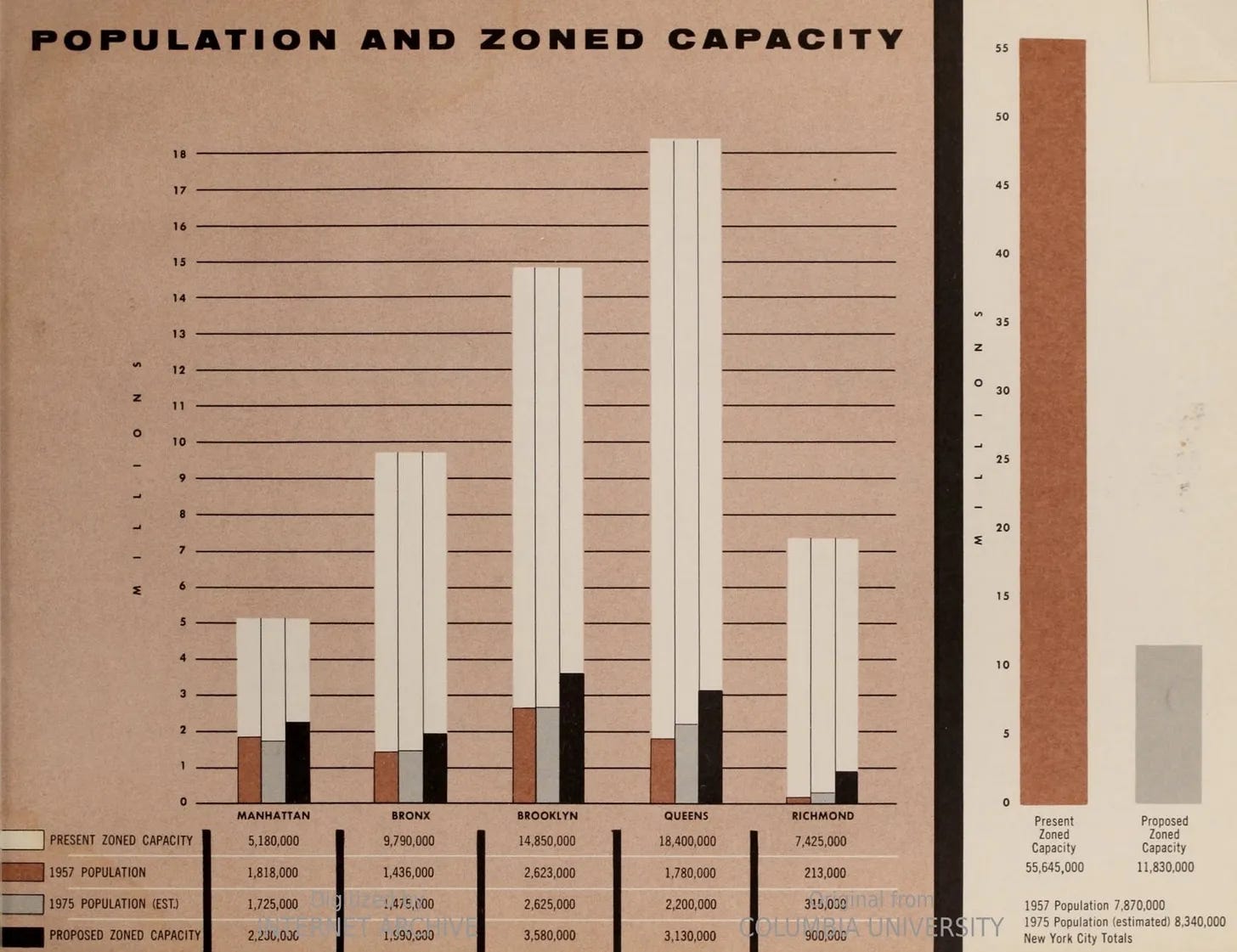

The scale of the downzoning was staggering.

Before 1961, zoning allowed for the city to theoretically house nearly 55 million New Yorkers; afterward, to an estimated 12-to-16 million. Later, Bloomberg-era rezonings reduced the amount of land available for low-density multifamily housing by 37% citywide, further entrenching much of the city’s low-rise character. What’s been allowed to be built since is old: nearly two-thirds of the city’s housing stock predates 1961—three-quarters in Manhattan—leaving much of the physical shape of the city largely unchanged from my grandparents’ era.

Because the city has not been allowed to grow up, the population has barely grown since: the population increased from 7.8 million in my grandparents’ time to less than 8.5 million today, an annual growth rate of about 0.13%—and Manhattan remains about 25% below its 1910 peak. Despite essentially flat growth, the city has become infamously expensive. Walking around New York last month, I couldn’t help but feel that this was the legacy: a place that, like Mike Todd and Liz Taylor’s party, felt extravagantly empty. Not the streets—the sidewalk ballet was alive and thriving—but the space above them. Despite all the famous skyscrapers, New York City is surprisingly short: the average building height across the five boroughs is just 27 feet, barely three stories.

There aren’t enough places for people to live—and yet there is so much available vertical space in which they could.

This matters, because Manhattan is not just under-housing its own residents—it’s exporting its crisis to the entire region, and to the rest of the country as displaced families move to cheaper metros in the Sunbelt.

Yet New York City remains the economic engine of the region, creating some 4.7 million jobs alone. Unable to house them all, nearly 1 million people commute in daily from outside the city. Of those 4.7 million jobs, 55% are in Manhattan—which means that for each of the 900,000 Manhattan residents working in Manhattan, about two more commute in from the other boroughs and metro area. While many may prefer the suburbs, a lot would rather avoid the nation’s longest commute. To wit, the citywide vacancy rate is just 1.4%. In Manhattan, the median monthly rent hit a record $4,700 in July. Demand for housing in the city’s core is unmistakably high.

Yet while the job engine of Manhattan roars, the housing engine of Manhattan sputters.

New York City is projected to deliver about 14,500 apartments this year—less than Austin, a city one-eighth its size—but the rest of the metro area is picking up the city’s slack. I recently wrote about how New Rochelle, a suburb 20 miles north of Manhattan, has managed to increase its housing stock by 37% over the past decade while keeping rent growth below 2% since 2020—a time in which rent has grown by 25% in New York City. New Jersey has also been building housing for Manhattan workers, most notably in Jersey City.

During my visit, I took a trip over to Journal Square, about five miles west of Downtown and 20 minutes on the PATH commuter train. When I first visited in 2005, the area was rundown—parking lots and low-rise buildings dominated by the brutalist concrete monolith of the Journal Square Transportation Center. What was once the vibrant commercial heart of Jersey City had been bulldozed in the urban renewal era to create a commuter hub for suburban drivers. Today, the Transportation Center falls in the shadow of a half-dozen residential skyscrapers.

Jersey City adopted its Journal Square 2060 Redevelopment Plan in 2010, allowing tall, mixed-use density around the PATH station, stepping down as you move farther from the square. Between 2010 and 2022, the city expanded its housing stock by nearly a quarter—about 26,000 new homes in just over a decade, with another 12,000 expected by 2028. If New York City had matched that pace, it would have built closer to 800,000 homes instead of the 200,000 it actually delivered. The gap—hundreds of thousands of missing apartments—shows how much room New York has refused to make for those who want to live there. While Jersey City is expensive by national standards, its median two-bedroom rent of $3,180 is still far below Manhattan’s.

As a housing producer, Journal Square is a success story. But housing alone doesn’t make a neighborhood. Walking around, the scene seemed straight out of Pixar’s Up: single-family homes sat next to fifty-story towers. At their bases, though, were private lobbies and blank plazas. As Andrew Burleson might put it, what was missing were the “interfaces”—the connections between buildings and the spaces they create. People live in Journal Square, but they don’t linger there.

A few blocks away, India Square tells a different story. Exempted from the redevelopment plan, it remains a low-rise South Asian commercial district lined with groceries, shops, and restaurants. The buildings meet the street, the sidewalks are full, and people spill out from businesses into shared spaces. We stopped there for a meal, joining a crowd that felt alive in a way the bases of the towers did not.

The contrast is instructive. The Journal Square redevelopment copied Manhattan’s towers but not its streetscape. The best neighborhoods in Manhattan are defined not by their height but by the density of street life, activated by well-designed interfaces between buildings and streets. Broadway on the Upper West Side or Third Avenue in Murray Hill show how towers with continuous retail, restaurants, and services can feel welcoming and neighborly, even at a completely different scale to vibrant low-rise neighborhoods like the West Village. Although the buildings are tall, the streets are human.

To “Manhattanize” a place is not just to build high, but to build dense and fine-grained. It’s about stacking thousands of people vertically while giving them thousands of small encounters horizontally. Journal Square is a housing success story, but also a cautionary tale: it’s far harder to recreate the organic urbanism that originally emerged than it is to destroy it.

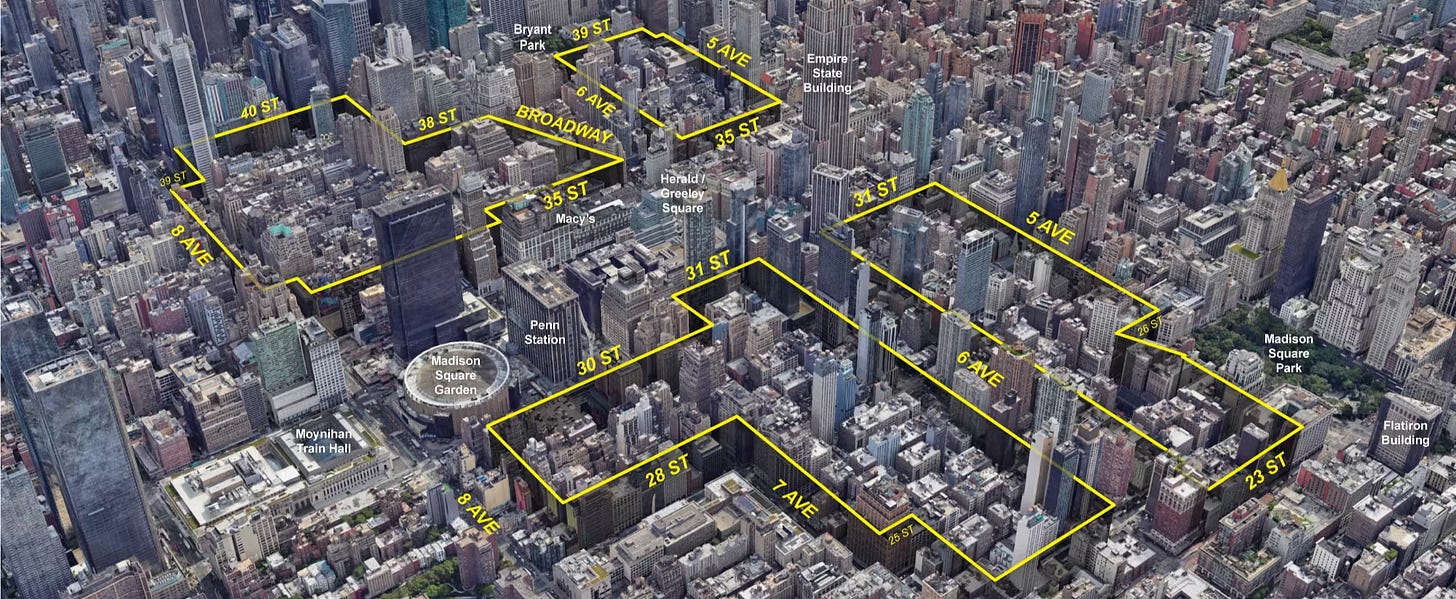

Back on the other side of the Hudson, there’s a place where the urban fabric still very much exists—and with abundant, extravagantly empty vertical space: Manhattan itself. I don’t think the entire island needs to look like Midtown or Downtown to house everyone who would like to live there, but there are plenty of transit-enabled neighborhoods that could easily handle more density. The city recently took a step toward Manhattanizing Manhattan in passing the Midtown South Mixed-Use Plan, which allows nearly 10,000 new homes in formerly commercial-only districts across forty-two blocks. Along with last year’s passage of the City of Yes for Housing Opportunity initiative, the city estimates that these reforms will unlock up to 130,000 new homes citywide—important, but hardly enough to meet demand. The city’s problem isn’t space; it’s political will—and overcoming the pervasive “Culture of No” that prevents it from becoming a City of Yes.

My grandparents left New York for the Connecticut suburbs in 1958, unable to afford to start a family in the city even with free housing.1 Sixty-seven years later, a one-bedroom apartment in their old building rents for $5,000, and the city’s shape looks much the same. It shouldn’t. Many more people would love to live in Manhattan today, if the city would allow it, yet so many of New York’s leaders are stuck in the midcentury mentality that urban density is a disaster, rather than the engine of prosperity it actually is and has proven to be.

Downzoning has made New York too expensive and too exclusive. To keep Manhattan from becoming a luxury product, it needs to make more Manhattan—not by expanding the island, but by filling the empty space above it with homes. Otherwise, Manhattan will keep exporting its crisis to the rest of the region and the nation.

Manhattan is for people—and if it Manhattanized, it could be home for many more of them.

My grandfather also found gainful employment, and eventually turned his penchant for showmanship into a career in radio, while pursuing acting in community theater.

I like the general gist here but I get irked by comparisons like Manhattan is only building 14,500 units, less than Austin a city 1/8 its size. Manhattan has a population density of 73,000/square mile. Austin I believe has 1,100 per square mile. It's sort of a cheap shot, I think, to not look holistically at the issue of how much New York has already built and how dense it and the surrounding boroughs are when compared with everywhere else. Sure, it's not building a ton in 2025, but it has built a ton and done it with density. It doesn't excuse anti-construction policies today, and sure New York could get denser and build more, but it's sort far beyond everywhere else in the country in terms of density that complaining about it feels unfair to me!

Any building has to be done with sensitivity. The Pennsylvania Hotel across from Penn Station was torn down but might have been able to have been remodeled and renovated. Should we tear down viable buildings that are inhabited and build taller, often glassier and uglier ones in their place? And what about financing new housing. In any case, housing yes, casinos no!