Out of Place

Rebuilding Social Trust by Making Space for Everyone

At the end of a long week, we’ll walk our dog to a local spot called Sour Duck, sometimes with friends. Located at the nexus of several neighborhoods, this bakery-café-bar-and-beer-garden is typical of Austin: lots of open-air seating at picnic tables, a small indoor space, a varied menu featuring local food and drinks, kids and dogs welcome, no reservations. It’s usually packed at happy hour with dog dads like us, plenty of parents with human children, and a few familiar faces from the nabe.

We’re lucky to live in a place with a variety of community spaces in which to hang out—apparently some 20% of Americans say they have nowhere to go.

Last month, the AEI’s Survey Center on American Life published a sobering report on the state of social and civic participation. The short version is that the decades-long downward trend in community engagement Robert Putnam first identified in Bowling Alone is still well underway. The consequence is that we have weaker relationships, less vibrant communities, and political discord, especially at the national level.

One reason why is that so many Americans are out of place—literally.

Americans don’t have anywhere to go to engage with their friends and neighbors. While half of survey respondents reported having access to parks, dog parks, and community gardens, large majorities reported having no access to other types of “third places,” community spaces like libraries, coffee shops, athletic facilities, watering holes, markets, hair salons, and bookstores. While larger numbers report having restaurants and diners as community gathering spaces, it’s still less than half the public. Strikingly, one fifth of all Americans report having no access to any type of third place, whether commercial or public.

Forget bowling alone—there’s nowhere to bowl. Visiting my hometown of Wallingford, Connecticut, recently, I came across the old bowling alley we frequented as kids. It’s been closed and vacant since 2018.

The lack of third places is hurting our relationships. The authors note that the “density of civic infrastructure and the robustness of American friendship networks correspond remarkably closely.” In other words, people with less access to civic infrastructure like public and commercial third places have fewer friends and a harder time making friends. With so many Americans having limited to no access to civic infrastructure, we should not be surprised that 17% report having no close friends. To make things worse, 44% of Americans report that few or none of their friends live nearby.

America has become a nation of lonely people.

Walking provides some Americans with opportunities to engage with their neighbors. Fifty-five percent of Americans go for a walk around their neighborhood at least once per month, and while they are more likely to interact with their neighbors, still 50% of walkers report that they rarely interact with neighbors they don’t know. Majorities of Americans in cities and suburbs (63% vs 58%) at least occasionally walk around their neighborhoods, but only 33% of rural Americans do.

Most Americans live amongst strangers.

Meanwhile, we’re participating in fewer and fewer groups. Only 33% of Americans are likely to be members of religious organizations, while only 7% belong to labor unions, 17% to hobby or activity groups, 15% to neighborhood associations, 10% to sports leagues or workout groups, and 16% to parent groups or youth organizations. Community participation is rare across the board.

The net effect is that we have fewer friends, we trust each other less, and we are less likely to see ourselves as part of a broader community, which in turn makes us less likely to participate in local events and social activities.

The report frames this as a problem of the divergence between college educated people, who tend to have more “social capital”—the networks, norms, and trust that enable people to work together toward common ends—and those with only a high school degree, who tend to have fewer friends and lower levels of social and civic engagement. The disparity is wide enough that the authors conclude that “the ability to cultivate strong social support is a privilege reserved for the college-educated, rather than an ordinary feature of American life.” But what stands out was not the class divergence but the low levels of engagement regardless of educational attainment—large majorities of people with bachelor’s degrees still have limited access to third places, less engagement with their neighbors, and low participation in their communities.

A lack of strong social support seems to be an ordinary feature of life for all types of Americans.

This is in part an access problem—people don’t have enough third places to go to—but there’s more to it. Even when they have access to third places, many fail to use them. Why? The authors identify financial concerns and a sense of non-belonging as potential factors that discourage people from engaging in civic life. But perhaps people find it easier to spend their time online or more convenient to stay home in our on-demand world. The lack of access and these other factors may have contributed to a broader cultural shift: we’ve grown accustomed to social isolation.

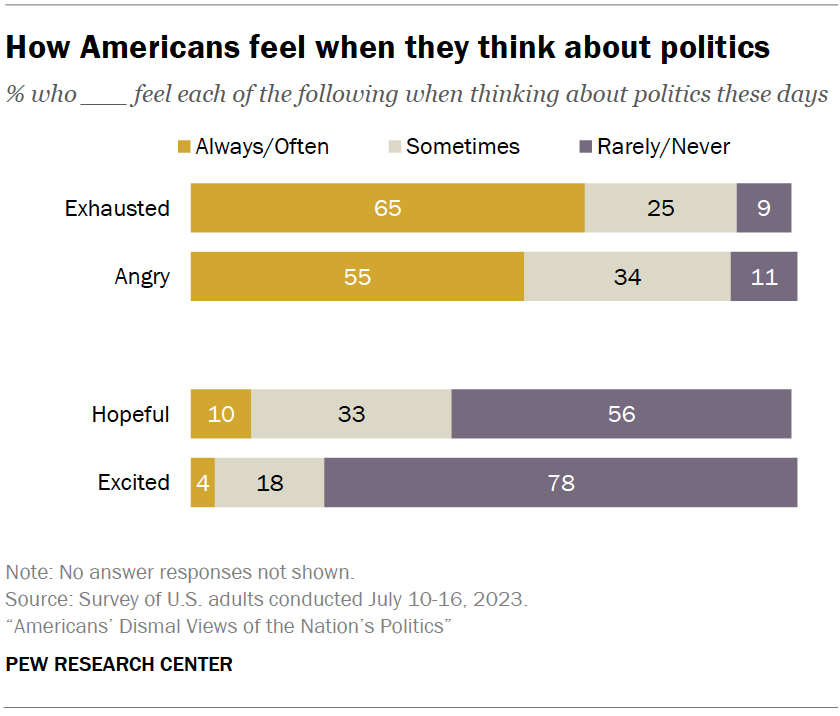

Low social capital has weakened our local communities, but it also manifests in our poisoned political discourse, in low voter turnout, in the decline in the quality of our civic institutions and the people who run them. Americans are roundly dissatisfied with the status quo and condemn our political system and politicians alike. As Pew found in a September 2023 survey, nearly 80% of Americans describe politics in negative terms—“divisive,” “corrupt,” “messy,” “polarized.” Only 16% say they trust the federal government, while 63% are dissatisfied with their political options. Unsurprisingly, 65% of Americans report being “exhausted” by politics.

Who can blame them?

At the same time, isn’t exhaustion what you’d expect in a society with low social trust? When so many people barely have friends, when so few engage with their neighbors, of course people would view politics negatively—they likely don’t see themselves as part of the body politic. They view themselves as apart from the people who have wound up running our political institutions, without realizing that they are a part of the system that put them there. If we don’t see solutions to our political problems, it’s because we fail to see that politics is people—and we just don’t see each other all that much, whether at our third places, in our neighborhoods, or in the community.

Perhaps it’s because a lot of us don’t want to. As I described in “Jerry’s Apartment”, we seem to have lost the “social habit.”

In the postwar period, technological and social changes reshaped how Americans interacted. Government policies like subsidized suburban sprawl and urban renewal contributed to the decline of long-standing communities, but other factors were equally impactful. Television brought news and entertainment into the home, while the internet and social media altered social habits in ways we are still unpacking. Movements like women’s and gay rights also shifted social dynamics. Incidentally, in the years after the first state-level legalization of gay marriage, 37% of gay bars—once vital third places for gay people—shuttered, ironic given that the movement began at a gay bar. Other factors, like evolving attitudes toward work, generational values, and political turbulence further contributed to shifting social habits.

The takeaway is not that our bank of social capital would be richer if women were forced back into the kitchen or gays back into the closet, or that we’d be better off without all this newfangled technology. Rather, it’s that culture and the built environment impact social habits as much as social habits impact our built environment and culture—they reinforce (or weaken) each other.

If we want to see improvements on a national scale—less frustration, less fatigue, and less political discord—we must first focus on replenishing the bank of social capital in our everyday lives, by changing our habits. We will not be able to achieve anything resembling a national spirit if we are unable to find or create one in the neighborhoods and communities in which we live. National change doesn’t happen in a vacuum; it starts with what we build in our own neighborhoods and how we engage with the people around us.

Creating more spaces for people through typical urbanist remedies like building more sidewalks, allowing for greater density, and legalizing mixed-use neighborhoods can help—but more importantly, we have to make space for other people in our own lives. We can make more parks and sidewalks, more Sour Ducks and gay bars, more PTAs and neighborhood associations, we can have more walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods—but these pathways to better, more vibrant communities will go untrodden if people don’t make an effort to change their social habits. If we want to change our national politics, first act local: talk to a neighbor, meet up with a friend, or go for a walk in the neighborhood.

Somebody has to take the first step.

Thank you for reading City of Yes. If you enjoyed this, the best way to support my work is to share with friends and neighbors—or leave a comment!

Excellent article- thank you, Ryan! My wife and I moved from Travis Heights to San Francisco last year, and besides rather desperately missing our son Judah, our daily lives have never felt better. Lots of factors here (including beautiful parks and our wonderful neighborhood, Inner Richmond), all of which ultimately come back to not using a car.

Social isolation has been gradually (and cynically) rebranded as personal efficiency, but the simple kindnesses and impromptu conversations afforded by walking and public transportation are priceless. These brief moments of connection with our fellow citizens reassure us that we're all part of something larger than our often insular worlds suggest.

I think you make a good point that we have to think both system-level and personal-level. Parks don’t work if we sit inside watching Netflix instead of going outside.

I think this is where the Strong Towns incrementalism approach can be most valuable.

To take the example of a neighborhood park: First notice the park is not well used, then ask what’s the smallest thing we could do to make it better (probably some shade and some benches!). Do that thing right now — not after a ten year study; now!

The interesting thing is that we can and should do that work together, as a community of interest. The more we work together, the more things get better, the more we want to work together.

What little piece of community fabric can you and your neighbor adopt as a project? Start small but stick with it, and it’s amazing how much things can improve with time.