Take Me to Church

A Sacred Place for Secular People

In almost every religion, fire symbolizes divinity, purity, and transformation. The fire that nearly destroyed Notre Dame Cathedral in 2019 was not divine intervention, but it presented an opportunity to reimagine the role of sacred spaces in an increasingly secular world. The French government solicited ideas for how to redesign or repurpose the 860-year-old building: architects proposed modernist steeples, glassy atriums, and roof gardens; others proposed turning the building into an event and entertainment space, or a community center and museum, or a beacon of environmental sustainability, covering the cathedral in wind turbines and solar panels. In the end, the French state decided to spend $760 million to restore Notre Dame to its pre-fire form and original use. This may seem strange for a country in which around half of the population reports no religious affiliation, but what France ultimately chose to do was to rebuild a sacred space for a largely secular people.

The decision reflects a deeper truth: even in our modern, digital age, people still need spaces that offer meaning, connection, and transcendence. Secular people need sacred places, too, but they don’t have very many of their own.

I’ve discussed how the decline of “third places”—community spaces like libraries, coffee shops, bars, markets, salons, and bookstores—has contributed to a decline in social trust, civic engagement, and personal relationships. Diana Lind has written how, on top of the loss of third places, the decline of “second places” (workplaces) is further contributing to a “human doom loop.” It’s no surprise that sacred places are also in decline when 28% of Americans identify as atheist, agnostic, or “nothing in particular”—the “nones,” as some have taken to calling us.

Yes, I’m among the nonbelievers. I was raised Catholic, but I left the Church in high school after a period of soul-searching and exploration of other faiths. Religion does not have a monopoly on systems of belief, but for most of human history it was the primary means by which people fulfilled certain needs integral to human life: the quest for meaning and purpose, systems of values to guide our actions, rituals to mark the passage of time and the vicissitudes of life, a feeling of belonging to a community of shared values, and a sense of transcendence. Ultimately, I realized I had irreconcilable philosophical differences with the faiths I explored, but like many other nonbelievers, I found alternatives in philosophy and elsewhere that have helped me to lead a fulfilling, engaged life.

But I’ve never found anything that fully replaces the role of a physical church.

That physicality, that sacred place, is key to what makes religion stick, I think. A church—or a synagogue, mosque, temple, gurdwara, or whatever any religion calls their house of worship—serves primarily as a place to bring people together. They demarcate, often through beautiful architecture and art, a physical separation from the outside world; they are arranged to focus the attention of those assembled toward solitary contemplation or common activities like prayer, song, or hearing sermons; and altogether they facilitate a sense of connection—to each other, to God, to Nature, to the universe. Churches provide a physical space in which to find solitude alone or to commune with fellow travelers.

While religious spaces are designed to meet these needs, secular spaces attempt to replicate some of their functions but often fall short. Lecture halls gather people to hear speeches or presentations, music halls bring together people to share in beautiful music, libraries are a venue for both quiet and shared study, spas and other wellness centers offer places for meditation and contemplation, community halls and recreation centers are spaces for gathering and celebration, museums are for the enjoyment and exaltation of great art, skyscrapers have been called “cathedrals of commerce.” These places are often designed to awe and inspire, to focus the attention and to transport their audience from the mundane to some place else spiritually or intellectually—but they are limited. It’s difficult to fully appreciate great art when the halls of the Louvre or the Met are crowded with Instagramming influencers. A yoga studio will never quite fully lift one’s spirit off the mat. What makes a space sacred is not a hodgepodge of functionality or beauty in isolation, but an integration of intentional design and purposeful action.

It’s hard to accomplish, even at existing secular temples.

My favorite example is the Panthéon in Paris, a secularized church across the Seine from Notre Dame. Originally constructed to honor a Catholic saint, the building’s religious status changed almost as frequently as the French government, before it finally settled into its role as a patriotic temple glorifying La République. Inside, the nave is decorated with allegorical paintings and sculptures celebrating French values and individuals, crowned by an airy dome from which swings Foucault’s pendulum. In the crypt beneath all that are the graves of the heroes of France—Voltaire, Rousseau, Hugo, Dumas—and above the dome is a colonnade from which to take in glorious views of Paris.

One could easily imagine, with the addition of chairs and a lectern, an orchestra and choir, candle light and the scent of lavender, how it might be transformed into a sacred space for the contemplation and celebration of French civic virtues and holidays. But as it is structured and programmed today, it is mostly a wonderful space to admire and photograph, rather than to experience the sacred. It’s close but not quite there.

But “not quite there” still leaves out quite a lot. The decline of religion globally has left a spiritual vacuum: modern secular people have no place to go, while many traditionally sacred places today sit empty.

For the Catholic Church, the problem of decline is as much a crisis of faith as it is of real estate. Some years ago, while looking for space in San Francisco for our secular Montessori school, I toured several religious facilities that the Church was trying to dispose of. Designer Ken Fulk had already turned one cathedral there into the swanky Saint Joseph’s Art Society, which Architectural Digest described as “part members’ club, part retail concept, part cultural center.” Others have become luxury condos, answering the unasked question, “Is nothing sacred?” Outside of godless San Francisco, a former church in my Austin neighborhood has become a coworking and event space, aspirationally called “The Cathedral.” I suspect, as our society continues to secularize, that more churches and religious spaces will find resurrection as functional, secular spaces.

But what if some of them were reborn, much as Notre Dame was, as sacred places for secular people?

Imagine an American Pantheon, a sacred civic space graced by statues of Liberty and Justice, with crypts entombing distinguished patriots and eminent citizens. Sunday gatherings might include readings from foundational texts like The Columbian Orator and music from The Great American Songbook, with civic holidays celebrated with starred-and-striped bunting and barbecues. At quieter times, visitors could contemplate paintings of civil rights martyrs like Lincoln or King. It’s the type of space that could be replicated at different scales in cities nationwide, and there are already precedents: the dome of the US Capitol, the sacred home of American democracy, already has a fresco painting called The Apotheosis of George Washington, while the rest of Washington DC is dotted with secular temples to various presidents.

This is only an example of the type of sacred secular space that might exist, even if in this case, patriotism is also on the decline. Still, there’s an opening for something, or many somethings, to fill the void created by secularization.

Elle Griffin argues that secular humanism could be the future of religion. Meanwhile, Robert Tracinski contends that fandom for the fictional “universes” of Star Trek, Star Wars, or Marvel Comics—with their own mythologies, worldviews, and values systems—“serve[s] the same spiritual function as religion.” Alain de Botton wrote a book called Religion for Atheists, in which he attempts to rescue certain aspects of religion that he believes could still benefit nonbelievers. Others have tried to create secular churches, such as Sunday Assembly, “The Hot New Atheist Church,” and Civic Saturday, a “civic analogue to a faith gathering,” but they have struggled to gain traction. It’s early days yet.

So perhaps secular humanity first needs to figure out the what before we can worry about the where. But where does that leave us, in the meantime?

Possibly back in church.

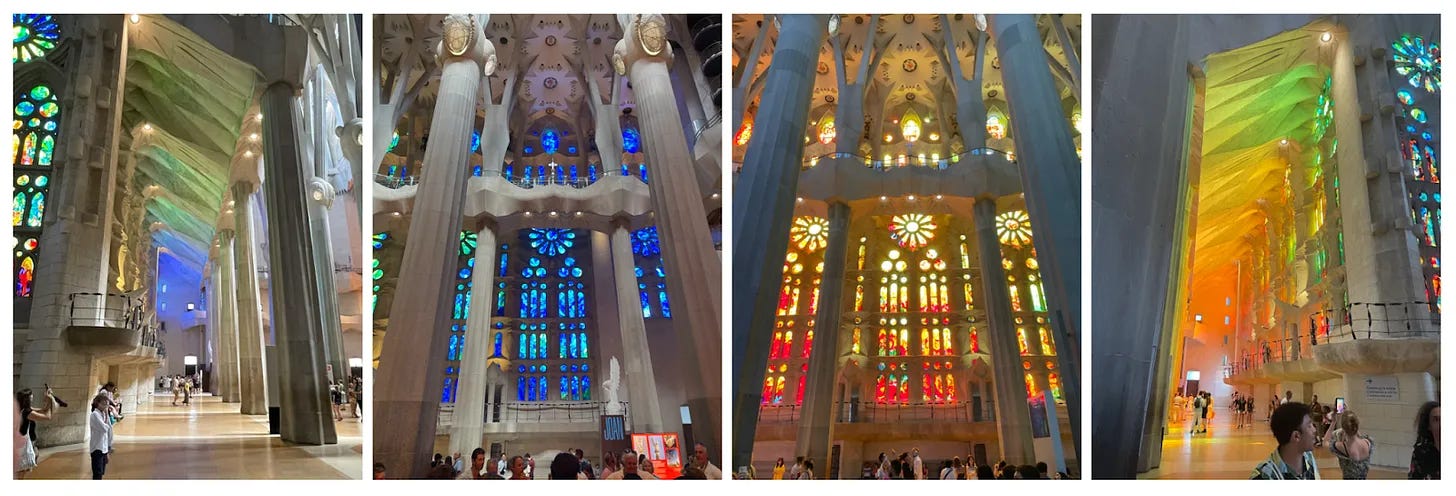

In August 2023, I celebrated my birthday with a visit to Gaudí’s Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, a truly spiritual experience that I described in “Two Cathedrals.” Inside that church, I wrote, the first thing that I noticed was the light:

Gorgeous, prismatic rays streamed in through monumental stained-glass windows, saturating the interior with ethereal color that made the soaring space glow.

I gasped upon entering.

It was then I noticed the treelike piers, the stone carvings, the translucent, molten mosaics of the windows, the people struck in awe by the sight of it all, looking up. Gaudí drew heavily on nature for his design, and the cumulative effect feels like a walk among the redwoods as sunlight filters through the leaves, all cast in stone and glass. While the exterior of the building is steeped and steepled in Catholic symbolism, the inside strips away the trappings of the Church to reveal God in the details.

Sagrada Familia was, of course, always intended to be a sacred Catholic space, but it is one that in practice has transcended religion. Inside, throngs of awestruck tourists of diverse backgrounds were having a similar, communal, and arguably transcendent experience. Gaudí imagined a space, whether intentionally or instinctually, in which all types of people could have one. He seemed to understand that people need places that invite us to experience something beyond the ordinary, that aspire to fulfill human potential and discover the “literal heights of our imagination, of our industry, of our spirit—and what we can do when we come together.” He appealed to the universal, that deeply human need for awe and transcendence that resides in all of us, whether we are believers or not. His cathedral reflects the basic architecture of humanity.

In our secular age, we need more spaces built like that.

However—and wherever—you spend the holidays, I wish you all the best. City of Yes will be back next week to close out the year. Thank you so much for reading, and happy holidays!

Sagrada Cathedral is truly amazing. And you’re right, the weakness of secularism is the lack of shared meaning and shared transcendence.

I had a similar experience when I entered Sagrada Familia. Afterwards, when I was sharing the experience with friends and family, I described it as an almost-secular cathedral.

Anyway, if you haven't read it, you might find this Atlantic article interesting: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2018/10/losing-the-democratic-habit/568336/