The Invisible City

The Hidden Cost of Austin's Capitol View Corridors

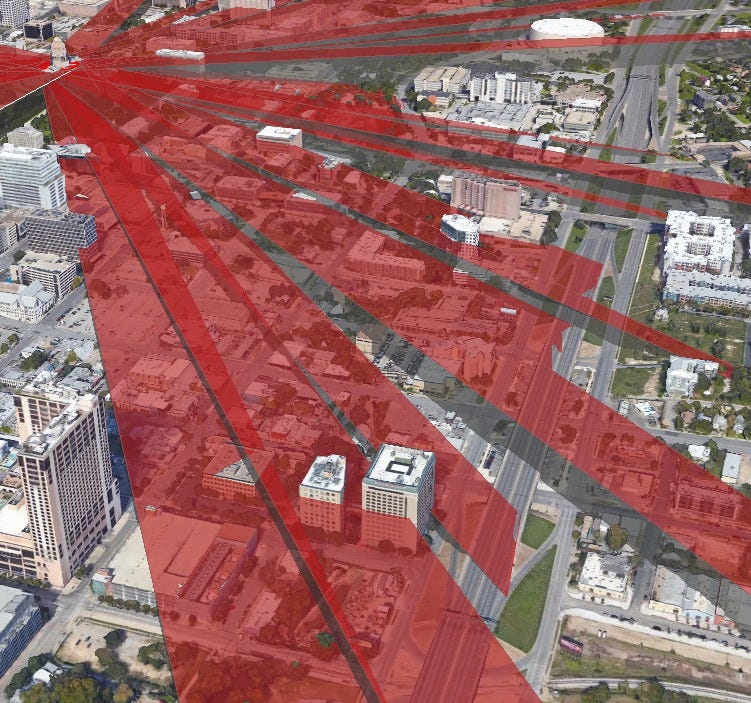

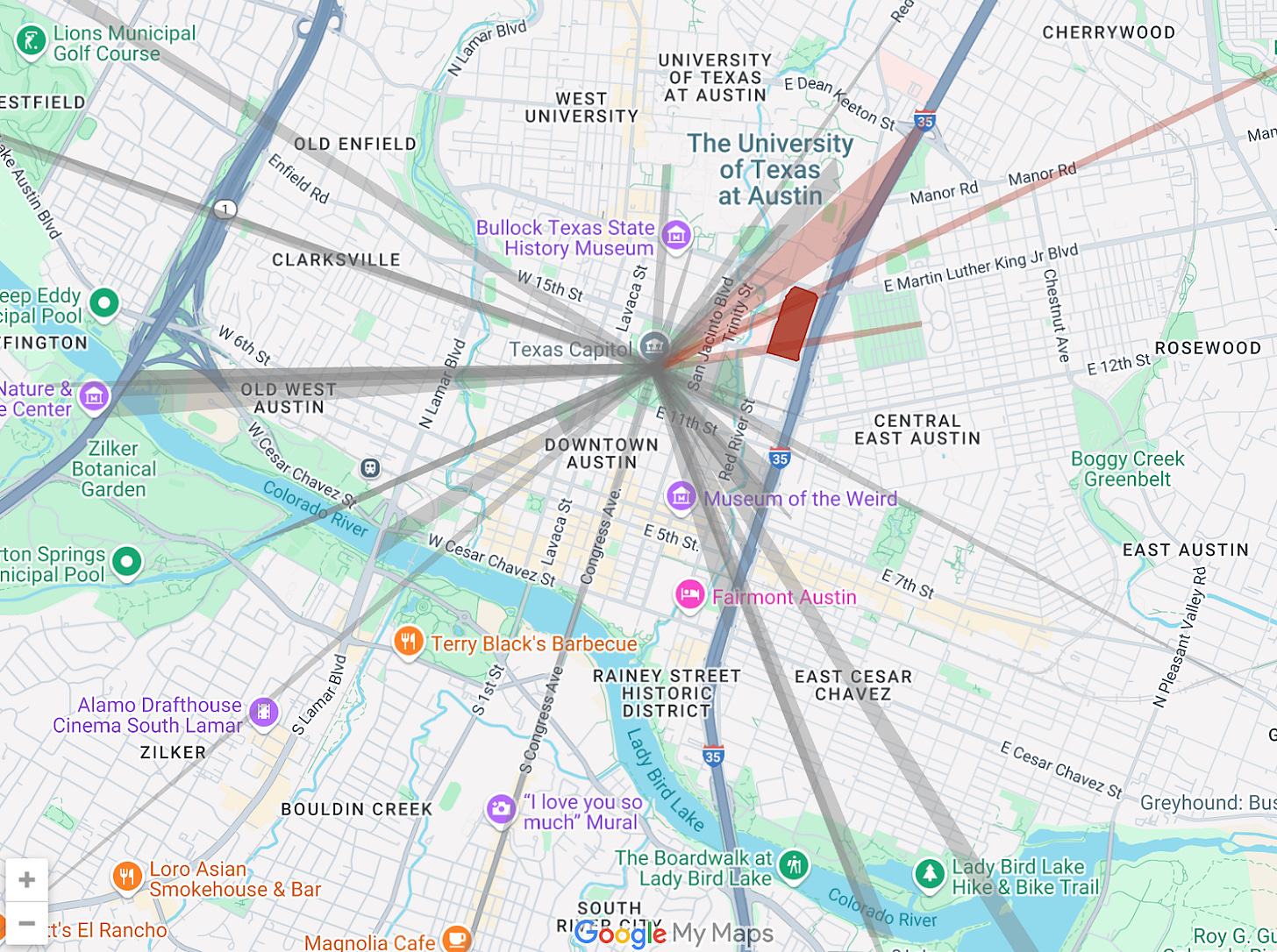

Over the past two decades, a skyline has risen from what once was a sea of parking lots in downtown Austin. Yet on downtown’s east side, parking lots still dominate—even where zoning allows skyscrapers. The parking lot at the corner of Trinity and E 8th Streets illustrates the contradiction. In theory, the owner could build a 120-foot tall building occupying 100% of the lot here by right; if they opted into the Downtown Density Bonus Program, they could build up to five times the allowed floor area with no height limit—something akin to the 58-story Independent tower on the west side of downtown. But in reality, nothing taller than three stories could be built there.1

Why not?

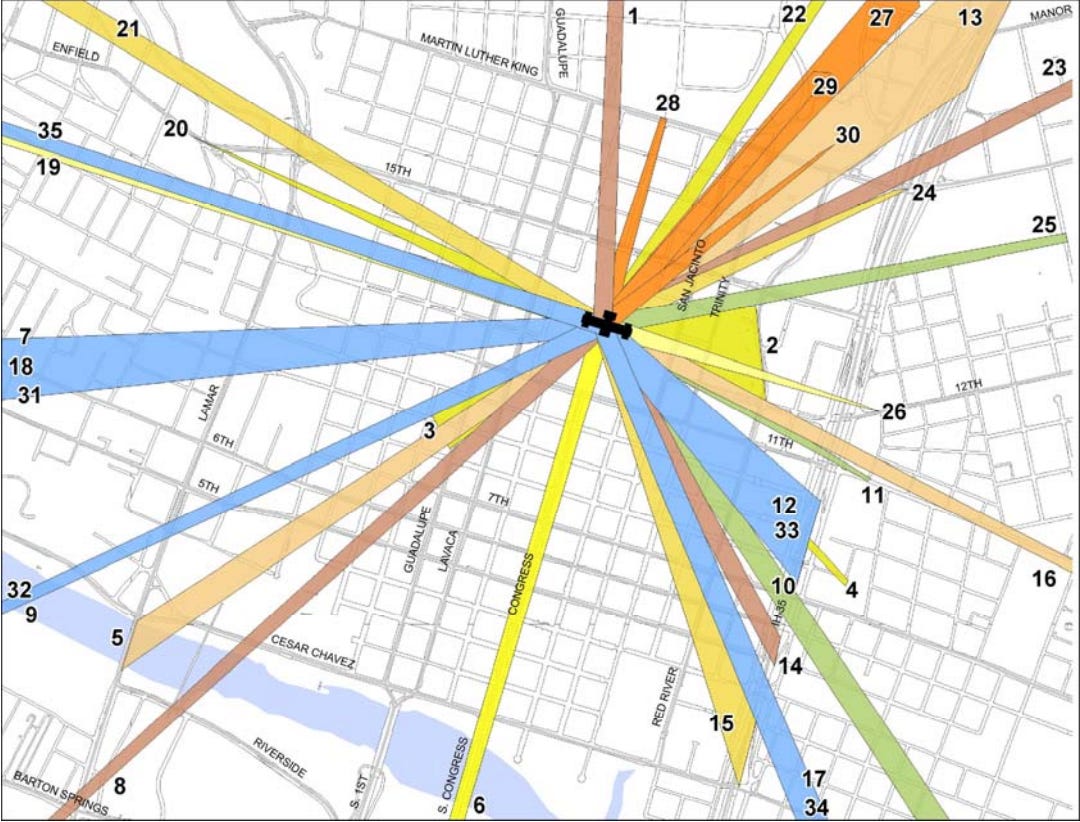

The answer is just visible from a corner of the parking lot, where you can see the tip of the Texas Capitol’s dome peeking up behind buildings a few blocks away. Across Austin, “Capitol View Corridors” (CVCs) protect views of the Capitol dome from twenty-six vantage points, suppressing building heights along the way.2 Created in 1983 to preserve sightlines as the first modern towers popped up in the 1970s and 80s, these corridors today function as invisible ceilings that keep prime parcels locked in low-value uses like parking lots—even where demand for density is highest. In the case of this parking lot, the unobstructed Capitol view is protected for drivers passing through Austin on nearby Interstate 35.

Height restrictions are a common—and often misused—tool in land use regulation. From Washington D.C.’s uniform skyline cap to Denver’s view plane restrictions, they distort land values and stifle growth. In Austin, Capitol View Corridors don’t just constrain downtown: they prevent it from becoming something more—something recognizably urban.

While drivers enjoy an unobstructed view of the Capitol, the view from within downtown is a dead zone of pavement. Consider the St. David’s Church garage, which sits on a similar-sized lot across the street from the Trinity Street parking lot—just outside the CVCs. While the church garage’s land is appraised at $650 per square foot, the parking lot across the street is valued at only $204, reflecting the suppressed development potential. In effect, the CVCs have erased $446 in land value per square foot—and corresponding tax revenue.

The CVCs make downtown Austin less valuable—not only to the tax base, but also as a place for the people who might otherwise live there.

This is a classic case of what economist Frédéric Bastiat called “the seen and the unseen.” We see the Capitol dome, unobstructed as we drive past on the highway, and we admire the view. What we don’t see are the homes not built, the businesses not opened, the tax revenue not collected.

The Capitol’s visibility isn’t free—it comes at the price of the invisible city it prevents from emerging.

That tradeoff might have made more sense in 1983, when there wasn’t much to downtown beyond the Capitol itself and few could foresee the vibrant, populated neighborhood that would emerge later. After the painful era of urban renewal, in which much of downtown was bulldozed for uninspired office blocks and the parking structures that served them, it’s easy to understand the urge to protect vistas of Austin’s most beautiful building. But downtown Austin today isn’t the Austin of 1983. It’s a desirable place for people and businesses alike—today, 15,000 people live there and 132,000 work there—and it could be more desirable if its remaining parking lots were allowed to evolve into something more useful. Instead, a fleeting glimpse of the Capitol is prioritized over the life of the city below it.

To help make downtown a better place for people to live in, work in, and visit—not merely to pass through—years ago, the city eliminated downtown parking requirements and upzoned the district. Ironically, CVCs have created a de facto parking mandate by making large parts of downtown undevelopable. The city may not require parking, but CVCs ensure parking lots are the only thing that can be built.

Some think this tradeoff is worth it. Several CVCs cover the east side of downtown, including most of the Red River Cultural District—home to iconic music venues like Stubb’s, Mohawk, and Elysium. They see the CVCs as “protecting” these venues from redevelopment pressure, an acknowledgement that CVCs lower land value and property tax assessments. Stubb’s and Mohawk are some of my favorite places to see live music—but this isn’t the way to protect them.

Suppressing land value imposes a deadweight loss—on nearby parcels, on the tax base, on the city’s future. It drains potential revenue that could directly support cultural institutions, treating stasis as preservation instead of offering active support. Even with artificially low land values, venues in the Red River Cultural District still face rising property taxes. If they need protection, the city has better options: grants, targeted height caps, transferable development rights, or streamlined redevelopment paths that preserve stages while allowing new construction above. The point is, if we want to preserve cultural assets, we need precision—not a blunt policy that freezes entire neighborhoods in place.

Lawmakers have already acknowledged that some views just aren’t worth it. A recent law eliminated four CVCs so that the University of Texas could build a cancer center downtown. That decision makes a lot of sense—saving lives is a better use of land than saving a view. Notably, one of the repealed corridors protected a view from the upper deck of I-35, a highway the state is now lowering below grade. Once the highway is buried, no driver will see the dome anyway. Fittingly, one headline said UT had been “freed from Capitol view restrictions.”

Why not also free eastern downtown?

Three more CVCs continue to protect views for northbound drivers on the soon-to-be-buried I-35—and limit downtown Austin’s future. When the legislature next convenes in 2027, repealing these should be a no-brainer. Still, even after eliminating those, there would still be 23 on the books, distorting land values not just downtown, but across the city. Two of these exist for the pleasure of drivers on high-speed roads in West Austin. While we might question the wisdom of giving drivers one more thing to be distracted by, lawmakers ought to review all CVCs to reconsider whether preserving every remaining view is still worth it.3 The best view of the Capitol, in my view, is from downtown—not beyond it.

In Austin, what’s seen is the Capitol dome. What’s not seen is the city that might have risen around it—because it was not allowed to be built. As Bastiat warned, focusing only on what’s visible means ignoring what’s lost. In the capital, there’s an invisible city waiting to emerge on empty lots. Ideally, the Capitol should inspire the city around it—not limit it. Texas lawmakers have the power to change the law to eliminate the most destructive CVCs. In so doing, they might give Austinites a reason to look up.

The opportunity to build a better capital city is not lost—it just hasn’t been seen yet.

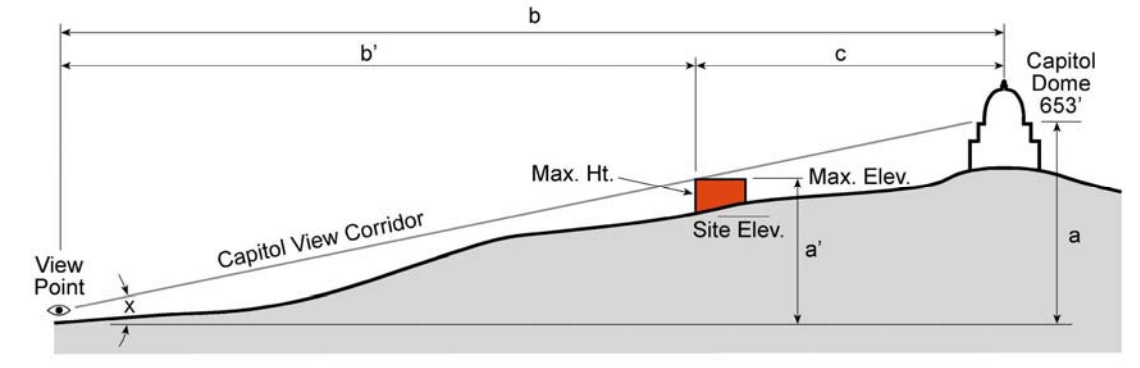

This is an approximation based on my estimates; the actual height of what could be built there is a function of geometry and geography. The CVCs are planes that slope down from 100 feet away from the "Center of the Capitol dome," a point at 653 feet above sea level, to specific Texas Plane Coordinates that demarcate the particular vantage points from which to see the Capitol. Easy enough, right?

Recently passed legislation struck four of the CVCs from the books.

And if the legislature decides to act, the City of Austin should update the city code, which largely mirrors the state’s view restrictions.

Fabulous article. Trying to protect views from high speed roads and highways is ridiculous, and honestly, probably all the CVCs are pointless. But the highway ones are the most absurd, and definitely need to go.

It’s interesting. I’m not a big fan of the CVCs and I agree that prioritizing views from the highway isn’t ideal.

At the same time I’m more ambivalent about height limits in general. One of the problems that makes it really hard to develop good urban infill is that the absolute maximum potential development is already priced into the land. So, ironically, even where there are no limits, the financial ambition of the surface parking lot owner ends up being the hardest limit of all. (I wrote about this earlier this year: https://postsuburban.substack.com/p/the-case-for-incrementalism)

I think the ideal — but not current practice anywhere that I know of — would be to have a general height limit tapering out from the city center but automatically increasing over time, either on a timeline or when some development milestones are hit. The reason is, that would actually suppress the value of the land in the short term, so that you could redevelop more of it from surface parking or single story buildings, to lots of 3-5 story buildings, creating a complete neighborhood. Instead what happens is you go from a big sea of surface parking to one skyscraper and a big sea of surface parking, leaving the overall area underdeveloped for much longer.

Of course in reality we almost always over-restrict development so I’d rather have no limits than harmful limits. But it’s tough because the global optimum for the city economy is for “thicker” development spread more evenly over a larger area, but there’s a lot of friction working against that outcome that’s not easy to circumvent.

I think this is where land value tax could be so helpful, again in the ideal world where we get these things, to apply financial pressure to act against speculative holdouts.

Meanwhile assuming this massive I-35 redo goes forward and takes those CVCs with it, will the increase in development be credited to the freeway expansion or the removal of the height limits? :)

Good article, lots of food for thought!