American Gridlock

Liberty, Order, and the Geometry of the City

Flying over the American heartland at 35,000 feet, one sees the stitched-together patchwork of our vast nation as an easily identifiable grid. Cities appear within the right angles of this checkerboard, with roads emanating outward in straight lines defining the boundaries of suburbs and then farmlands, covering some two-thirds of the land from Ohio to California. The Great American Grid emerged in defiance of the landscape, paying no heed to topography, climate, or history. It imposes itself over 1.4 billion acres, broken but not stopped by the mighty Mississippi or the majestic Rocky Mountains. From the air, one does not see political divisions, only the lattice that holds our country together.

Yet the pattern that united the continent has also long divided it: America’s anti-urban bias was written into the grid itself.

In the Land Ordinance of 1785, Congress created what became the Great American Grid to survey and sell the Northwest Territory one square mile at a time.1 Yet behind its utilitarian purpose lay an ideology. As Amir Alexander writes in Liberty’s Grid, the Cartesian geometry of the grid reflected a Jeffersonian faith that reason could perfect society. Ordering the land into equal squares was an attempt to order liberty itself, giving each man a blank space on which to inscribe his own destiny.

The grid, mapping limitless possibility onto blank space, was where Jefferson imagined American liberty would find its fullest expression. If Jefferson extolled the yeoman farmer as paragon of republican virtue, he saw cities as quite the opposite: “sores” on the body of the nation that sapped its virtuous soul. To create space for Jefferson’s ideal nation to grow meant creating space between its citizens: the grid reflected his antipathy to urban density, barely accommodating roads, commerce, and civic life—even though market towns were crucial centers of agrarian economies.

Despite the dominance of the grid, human nature proved more indomitable than Jefferson’s narrow view of human reason. Trade, transport, and community needs forced settlements to cluster along the survey lines. These “bastard offspring” sprung up across the plains, their streets conforming to the larger grid pattern. They revealed what Jefferson hadn’t foreseen: that the instinct to connect would find its own geometry. The young republic needed new cities and towns.

While the Jeffersonian grid became symbolic of the American West, that geometry would find no grander or more ironic fulfillment than in the fastest-growing city in the country: New York—a place Jefferson derided as the “Cloacina of all the depravities of human nature.”

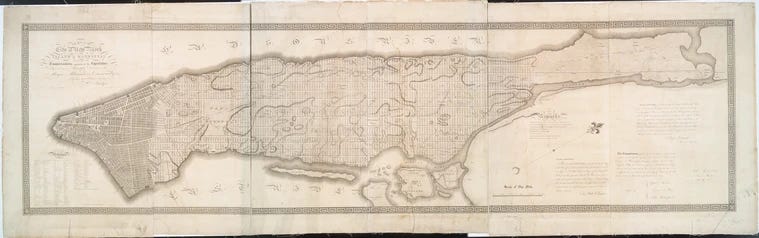

By the early 1800s, fast-growing Manhattan was straining against its northern borders. Recognizing the need to plan for growth, the New York state legislature passed an act in 1807 to appoint three “commissioners of streets and roads” to map the city’s future.2 North of Lower Manhattan, the commissioners would have the power of eminent domain to clear the way for the grid. Nothing, “neither existing streets, local needs, neighborhood tradition, or—most troublingly—property rights, would stand in their way.” The plan they delivered in 1811 was a striking network of uniform, linear streets and avenues that marched up Manhattan Island with few deviations. Disregarding the lay of the land and who owned it, “the map of future Manhattan is simply overlaid upon old Manhattan and replaces it, as if it were never there.” Indeed, some 40% of New York’s existing homes stood in the way of the new grid.

The Commissioners’ Plan of 1811 provoked outrage from landowners and elites alike. Many saw it as tyranny—a government redrawing the landscape in defiance of ownership and history. Clement Clarke Moore lambasted the “near-dictatorial powers” of the commissioners and mourned the loss of the island’s natural beauty. To writers like Henry James and Edith Wharton, the new city was flat, monotonous, bourgeois. Yet the irony endures: the grid’s power came from the very principle it seemed to violate: by imposing order, the commissioners created freedom—fixing the city in place so New Yorkers could move, trade, and build. What had looked like tyranny became the engine of prosperity and made New York the richest city on earth.3

In their remarks, the commissioners recognized the audacity of their plan, which laid out the whole of bucolic Manhattan Island as a city and made room for “a greater population than is collected at any spot on this side of China.”4 But their rationale was straightforward: dividing the city into regular, rectangular lots made construction, subdivisions, and sales easy. Despite the destruction of property rights, the grid became a machine for prosperity, creating immense fortunes from the order it imposed—even Clement Clarke Moore sold off his estate and became rich. The assessed value of city real estate exploded by more than fifty-fold between 1807 and 1887.

If Jefferson’s grid sought liberty through dispersion, Manhattan pursued it through density, using the same geometry to create not boundaries but connections. Its true invention wasn’t the parcel but the street: the shared framework that turned private property into public realm.

Jefferson’s grid abstracted liberty; Manhattan’s embodied it. Indeed, as Hilary Ballon writes in The Greatest Grid, the “the idea of the public realm in New York is inseparable from its streets.” The grid made civic life continuous, accessible, and visible. Where Jefferson’s coordinates divided, Manhattan’s intersected. Even Frederick Law Olmsted, who complained that the grid “subordinated buildings to the street wall,” inadvertently recognized its power: the streets, not civic monuments, became the city’s unifying civic form. Small lots, meanwhile, eventually forced the city upward, creating vertical monuments that would define its skyline. What Olmsted saw as constraint was, in fact, the condition of urban freedom—the framework from which a dense, democratic city could emerge.5

Olmsted correctly identified some drawbacks: the blocks were too narrow to allow alley service, which meant that services like garbage collection had to happen on the street—an oversight that plagues New York to this day. While the plan had been designed to facilitate east-west traffic between the wharfs on the Hudson and East Rivers, over time the city became a “longitudinal city,” where people lived Uptown and commuted Downtown. The 1811 plan didn’t include enough open space and north-south avenues, but it proved adaptable. Broadway would break the grid’s rigidity, while small parks would soften its grain.

As Romanticism emerged as a backlash against industrialization, the grid was seen as an enabling force of industrial capitalism trampling over nature. Genteel New Yorkers looked down on the European immigrants filling the city’s streets as much as the real estate barons filling their coffers. Journalist William Cullen Bryant wailed that “commerce is devouring inch by inch the coast of the island,” while landscape designer Andrew Jackson Downing complained that the gridded city was “always full.” Victorian moralists saw the density enabled by Manhattan’s grid as undermining republican virtue, not a landscape of liberty but the locus of immorality.

To save the republic, therefore, the grid would have to be destroyed.

So Bryant and Downing proposed “a vast anti-grid at the very center of the city in the form of an expansive, green, and naturalistic public park.” Central Park, as it came to be known, would eventually encompass six percent of the surface area of Manhattan. Designed by Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, it was a “rebuke” to the “confined and formal lines of the city.” And yet, by erasing the grid within its borders, Central Park strengthened it without. The park softened the city’s geometry without breaking it, making the surrounding neighborhoods more desirable and the urban fabric more livable. Its vast void became the city’s heart—the exception that proved the power of the rule.6

Later efforts to obliterate the grid would prove unintentionally anti-urban.

By the 1930s, a new generation of reformers turned the old Romantic distrust of the city into policy. What began as a moral yearning for light and air hardened into a bureaucratic campaign of clearance and control: the city itself became a problem to be solved. Chief among urban ills was the prevalence of the so-called slums. Reformers saw the potential for new housing on “superblock” sites, which would create free-standing towers surrounded by open space with no regard for the streets. Using eminent domain—not to open streets, but to erase them—the city cleared neighborhoods to make way for these “towers-in-the-park.”

Unlike Central Park, which became part of the fabric of the city, the superblocks erased the grid and “completely changed the grain of the city,” replacing short, permeable blocks with vast, disconnected parcels. The 1961 Zoning Resolution extended this anti-urban impulse across Manhattan, encouraging a proliferation of office “towers-in-the-plaza” that further eroded the grid and street wall. By the 1970s, these projects were “seen as isolating and destructive, [and] the superblock was scorned as deadening and antiurban.”7

What the midcentury renewers failed to recognize—which Jefferson intuited some centuries before—was that disconnected open space was anathema to the urban form. By the late twentieth century, the failures of urban renewal had discredited the movement, and planners embraced the street once more. In New York, projects like Battery Park City, Riverside South, and the World Trade Center restored the street grid and vitality to those neighborhoods.

A grid is not inherently urban; it’s merely a set of coordinates. How and at what scale it is measured determines whether it is fertile or fallow ground for civic life. Both the Great American Grid and the Greatest Grid reflect a distinct vision of the American Republic—and of the relationship between order and liberty. Whereas Jefferson’s grid equated freedom with independence and land ownership, Manhattan’s made liberty legible in its streets. Each expresses a different American faith: one in self-sufficiency, one in synergy—the prosperity that arises when individual energies converge. Where Jefferson imagined that wealth would arise on the open prairie, Manhattan showed what was possible when liberty was ordered to accelerate exchange, ambition, and civic energy. The 1811 grid is, as Hilary Ballon writes, “a heroic statement”—and New York is its living proof.

Two centuries later, New York and other cities have been cast as the villains in a national tragedy. Jefferson’s skepticism endures across swaths of the American heartland—mistrusting density, mistaking proximity for danger, conflating freedom with solitude. Populists once again rally against the city, mistaking its vitality for corruption, its diversity for decadence. The headlines make the old suspicion visible, but it is not new—the anti-urban bias is still embedded in the lines we drew across the country.

Yet cities remain the engines of our national life, and the cities that emerged on those lines are proof of our interdependence. The grid once promised that order and freedom could coexist—that we could build a republic both free and shared. Whether the grid still holds us together—or holds us back—depends not on the lines we inherit, but on how we live within them.

The rectilinear grid spread as the country gained territory, although the lot sizes eventually shrank to a more affordable 40 acres (farmers had to bring their own mule).

Officially, An Act Relative to Improvements, touching the laying out of streets and roads in the City of New-York, and for other purposes.

Preceding quotations from Liberty’s Grid: A Founding Father, a Mathematical Dreamland, and the Shaping of America by Amir Alexander.

From the “Remarks of Commissioners of the 1811 Plan.”

Preceding quotations from The Greatest Grid, edited by Hilary Ballon.

Preceding quotations from Liberty’s Grid.

Preceding quotations from The Greatest Grid.

If you look at farming towns in Europe, they create a central town that’s dense and the farms radiate away from the dense center. This is the exact opposite of what we have here where each farm has one house and everybody is extremely spread out, this has definitely led to a lot of rural people distrusting their neighbors and the public and anything “dense”. Its a real tragedy.

The world trade center destroyed a lot of buildings and neighborhoods, including Radio Row. The Rockefellers, Robert Moses, and others did a lot of damage. We lost

Pennsylvania Station, the Singer Building and too many other beautiful buildings!