Dungeons & Dragons & Housing

A Taxonomy of Our Chaotic Evil Zoning System

I have a confession to make: I’ve never played Dungeons & Dragons.1 Indeed, a lot of what I know about the fantasy role-playing game has been inferred from memes. You’ve probably seen some version of the one I’m thinking about: the so-called Alignment Chart, a 3x3 grid that describes a character’s worldview along two axes, morality and lawfulness. Morality falls along a spectrum of Good, Neutral, or Evil, while one’s orientation to laws and rules is Lawful, Neutral, or Chaotic. The chart yields nine personality types, recognizing that most people—dwarves, orcs, and dragons, too—do not fall neatly into a binary: they can be Chaotic Good, Lawful Neutral, or Neutral Evil, for instance. This framework has been used to describe taxonomies of everything from politics to sandwiches, even to other alignment charts.2

It’s also a useful way to think about land-use law.

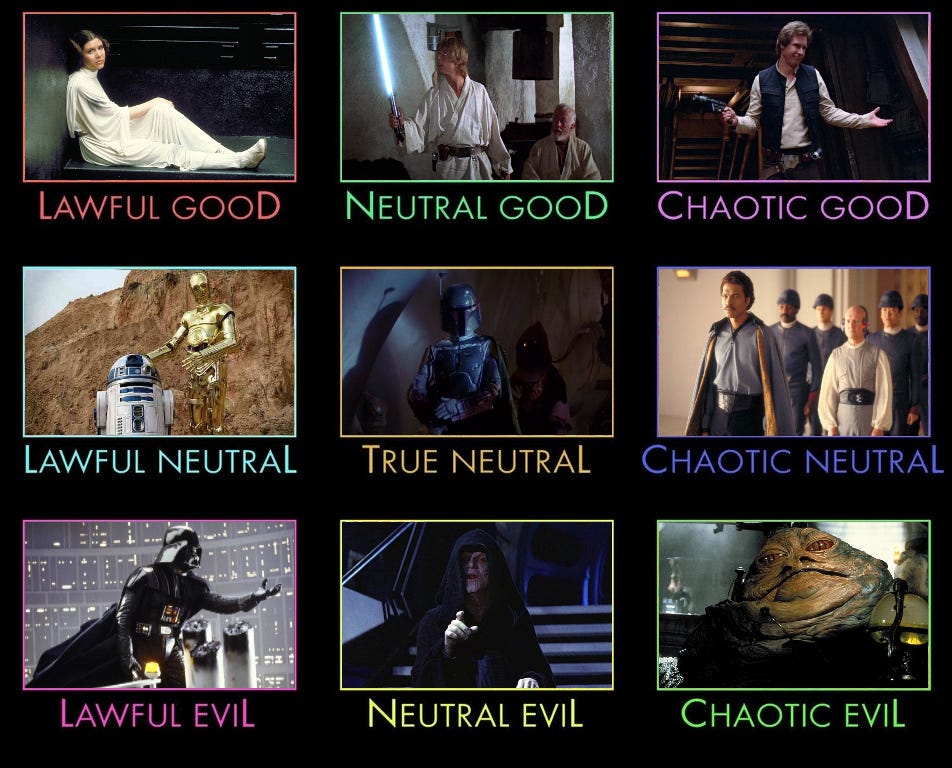

Before applying this framework to land-use law, it helps to see how it works in a familiar fictional universe. Since I don’t know the difference between a dwarf and druid, I chose Star Wars instead of D&D. The Good Guys in Star Wars are fairly easy to map onto the D&D framework: Obi-Wan Kenobi is the archetype of the Lawful Good who upholds the Jedi Code and fights for the values of the Republic; Luke Skywalker is Neutral Good, guided by his own moral compass rather than the Jedi Code; Han Solo is Chaotic Good, acting on instinct and playing by his own rules for a good cause. C-3PO is the exemplar par excellence of the Lawful Neutral: he’s obsessed with rules and terrified of breaking protocol, outcomes be damned. Among the Bad Guys, Darth Vader epitomizes the Lawful Evil—governed by an absolute belief in the Empire’s hierarchy and the rules-based order of the Sith—while the Emperor himself is Neutral Evil, more interested in the pursuit of power for power’s sake: rules, order, and institutions are subservient to his will.

With that vocabulary established, we can leave the characters behind in a galaxy far, far away and turn toward more terrestrial concerns. What’s useful about the D&D framing is that we can use it to think not only about characters, but about systems and policies, too, rather than flattening zoning reform into a good-versus-evil binary of YIMBYs and NIMBYs.

The goal of the YIMBY movement is (or should be!) the restoration of a system of Lawful Good, one based on the rule of law and grounded in the bedrock principles of American jurisprudence: equality before the law, transparency and legibility, due process, the presumption of innocence, and consistent enforcement. We want a legal system in which land use rules are clear, non-arbitrary, and equally applied; permissions are predictable and timely; opportunities for corruption and regulatory capture are minimized; and outcomes are oriented toward justice, not punishment or extraction. A Lawful Good land use regime would be a system in which by-right development is the norm; the code is based on objective performance, nuisance, or form-based standards; approvals are administrative, timely, and not discretionary; and applicants have the right to clear, time-bound appeals. The purpose of such a system is not to reward developers, punish NIMBYs, or to concentrate power. Rather, it’s to minimize the injustice that arises from nonobjective law and to reduce rent-seeking behavior and obstructionism. Such a system would be boring, legible, automatic, and deeply unheroic—bereft of villains and victims alike.

Most importantly, a Lawful Good system is one that enables housing development. Obviously, this is not the system we have in most of America.

Zoning presents itself, at least on its own terms, as a Lawful Neutral system: a value-neutral, rules-based framework designed—in theory—to impose order, predictability, and harm prevention through the separation of “incompatible” uses. Zoning was created ostensibly to protect single-family neighborhoods from noxious activities like slaughterhouses and chemical plants. But from the moment of its conception, it classified apartment buildings, neighborhood corner stores, and mixed uses as similarly “incompatible.” These determinations were not grounded in science or performance-based evidence, but established by arbitrary fiat, embedding aesthetic judgments and cultural preferences within a legal regime that claimed neutrality.

That system was sustainable only so long as cities did not change—which, of course, they always do. As municipalities evolved, fixed use segregation increasingly failed to map onto lived reality. Rather than allowing the code itself to adapt automatically, the system responded by creating exceptions: rezonings, variances, special permits, and overlays. What began as a system premised on categorical rules thus gave rise to a parallel regime of discretionary review, administered by neighbors, planners, zoning commissioners, elected officials, and an expanding constellation of environmental, design, and historic preservation boards. In this regime, the law was weaponized to slow, stymie, or stop housing altogether. Today, whether this system builds housing is almost beside the point. It exists for its own sake.

If the purpose of a system is what it does, then our land use regimes are certainly not neutral—and no longer lawful. Instead, we have a regime of Chaotic Evil.

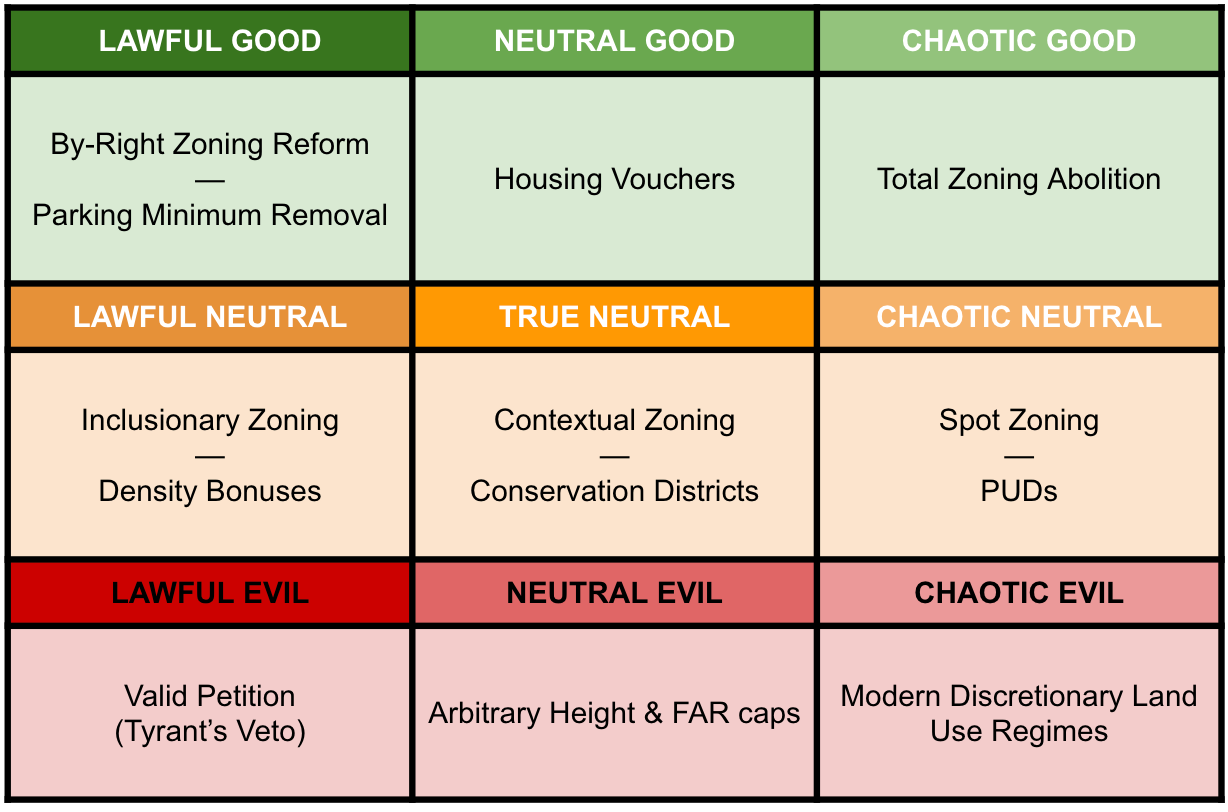

With that system-level diagnosis in mind, the alignment chart becomes a useful way to categorize housing policies—not by intent (theory), but by how they function (practice). Some policies reinforce a lawful, predictable system; others operate neutrally but entrench scarcity; still others actively empower obstruction. The chart below is my attempt to capture some of these distinctions at a glance.

One of the premises of the D&D Alignment Chart is that character profiles can drift, and the same is true of systems. No city adopts Chaotic Evil by ordinance. What begins as Lawful Neutral can, over time, slide—not because anyone chose malice, but because rigidity gives way to exceptions, exceptions give way to negotiation, and negotiation gives way to arbitrary power. The result is a regime that still looks lawful on paper but operates chaotically in practice, rewarding delay, extraction, and obstruction rather than compliance with clear rules. The housing crisis is best understood not as a failure of intentions, but as a failure to keep our land-use systems anchored to lawfulness. And so we have modern zoning regimes that are illegible, illiberal, and zero-sum—that almost require the invention of villains and victims to function.

Nevertheless, when pursuing political reform, it helps to think in terms of policies rather than personalities. This runs against the grain of contemporary discourse, which prefers stories of victims and villains. But most people involved in housing politics think of themselves as acting in good faith, pointing to a harder truth: our system of Chaotic Evil isn’t just the product of bad law, but the outgrowth of basic human biases. Aesthetic NIMBYism—the instinctive discomfort with change that does not “fit”—reflects a common preference for familiarity and visual continuity, not an ideology of exclusion. It’s best understood as a True Neutral orientation rather than a moral failing. But when that base instinct is entrenched in law and empowered to physically shape our cities, it produces and perpetuates systems of scarcity and exclusion. Over time, this accumulates as cultural ballast, embedded in the built environment itself, and extraordinarily difficult to unmoor.

Seen this way, the central conflict in housing politics isn’t between good people and bad people, but between systems that remain anchored to lawfulness and those that drift away from it. The alignment chart isn’t a moral scorecard; it’s a way of assessing whether policies reinforce lawful systems, or undermine them through chaos and discretion.

The housing crisis isn’t the brainchild of evil geniuses but the braindead progeny of a deeply flawed system. To fight such a system, and restore a system of Lawful Good land use, we don’t need to roll the twenty-sided dice and hope our YIMBY paladins can withstand the onslaught of demonic zoning enforcers. Ultimately, there are no dragons to be slain to get housing out of its regulatory dungeon—only bad policies.

What’s in your Alignment Chart?

I’m more of a Cones of Dunshire man, myself.

A ChocoTaco is not a sandwich.

I chose chaotic good because I’m so annoyed right now with the continuation of the density bonus program that I just want to tear down the whole zoning system!

Ryan,

This is wonderfully presented in a format that could be 'TED-Talk' worthy in my opinion. This is such a playful presentation that invites me to think about all the juxtaposition components and the planning synthesis involved in any decision space. Like you, I must admit I am not a gamer either, but I am a chess player and draw parallels from your words. There is a tool here to be fleshed out as an invitation for participation! Nice Read :)