Engineering Resilience in Flash Flood Alley

How Austin Survived the Storm—and the Next One

Over the July Fourth weekend, an estimated 1.8 trillion gallons of water fell over Central Texas—four months of rainfall in four hours. In Kerr County, west of Austin, the Guadalupe River turned from a wadeable stream into an impassable torrent, with an average flow rate exceeding Niagara Falls, sweeping away RV parks, campgrounds, and entire homes. More than 110 people were killed, including 27 children and counselors at the century-old Camp Mystic. Meanwhile, 100 miles away, 65 billion gallons of water rushed into Lake Travis, 20 miles upstream of Austin along the Colorado River. Yet downstream, the river held steady—and the city was spared. Why?

Austin’s very existence along a flood-prone river is the result of long-range planning and infrastructure investments. Indeed, the city has been engineered to survive flash flooding.

In Austin, urban resilience depends on climate resilience.

The Texas capital sits at the gateway to the Hill Country, a landscape shaped by water—and its absence. The rivers and creeks that carved its limestone hills are often trickles—or bone dry. Here, when it rains, it really does pour: this is an environment either parched or drowning. Early settlers discovered that its green grasses were a mirage: the soil was poor and the land dangerously flood-prone—one storm could wash away a family’s livelihood. The region earned the moniker “Flash Flood Alley.”

In the past, floods like last weekend’s would have surged down the Colorado River, just as in 1869—when the river rose by more than 50 feet and swelled to a mile wide, carrying off bridges, homes, and livestock in the capital. Further catastrophic floods in 1900 and 1915 destroyed Austin’s first dams, inundating the city and finally compelling the state of Texas to take action. In the 1930s, after several abandoned private attempts, state leaders and an ambitious politician found the will—and the financing—to finally address flood protection. Modeled on the Tennessee Valley Authority, the Lower Colorado River Authority (LCRA) was created by an act of the Texas Legislature in 1934. With then-Congressman Lyndon Johnson’s help, the LCRA received New Deal-era financing for the construction of a series of dams and reservoirs along the Colorado, including the Mansfield Dam, which created Lake Travis.

The system not only provides drinking water and flood protection for the Austin metro area, but the dams brought electricity to the Hill Country for the first time in 1939, while the reservoirs and lakes continue to serve as a source of recreation for Austinites. The Mansfield Dam alone cost $28.7 million—around $625 million in today’s dollars—and the entire system has required billions in maintenance and upgrades since. Resilience isn’t cheap.

Despite the massive upfront investment and ongoing maintenance costs, the investment has paid off many times over. A vibrant, wealthy city has grown along the river that once kept its growth in check, and today that real estate supports tens of thousands of homes and jobs on some of the most valuable land in Texas. None of it would exist without the LCRA. Indeed, even though Austin was spared the worst of the storm, the LCRA system prevented what would once have been catastrophic flooding—now for a much more populated and built-up city. Yet, in an area sculpted and interlaced by creeks and rivulets, even that system is not enough to protect the city from all flooding.

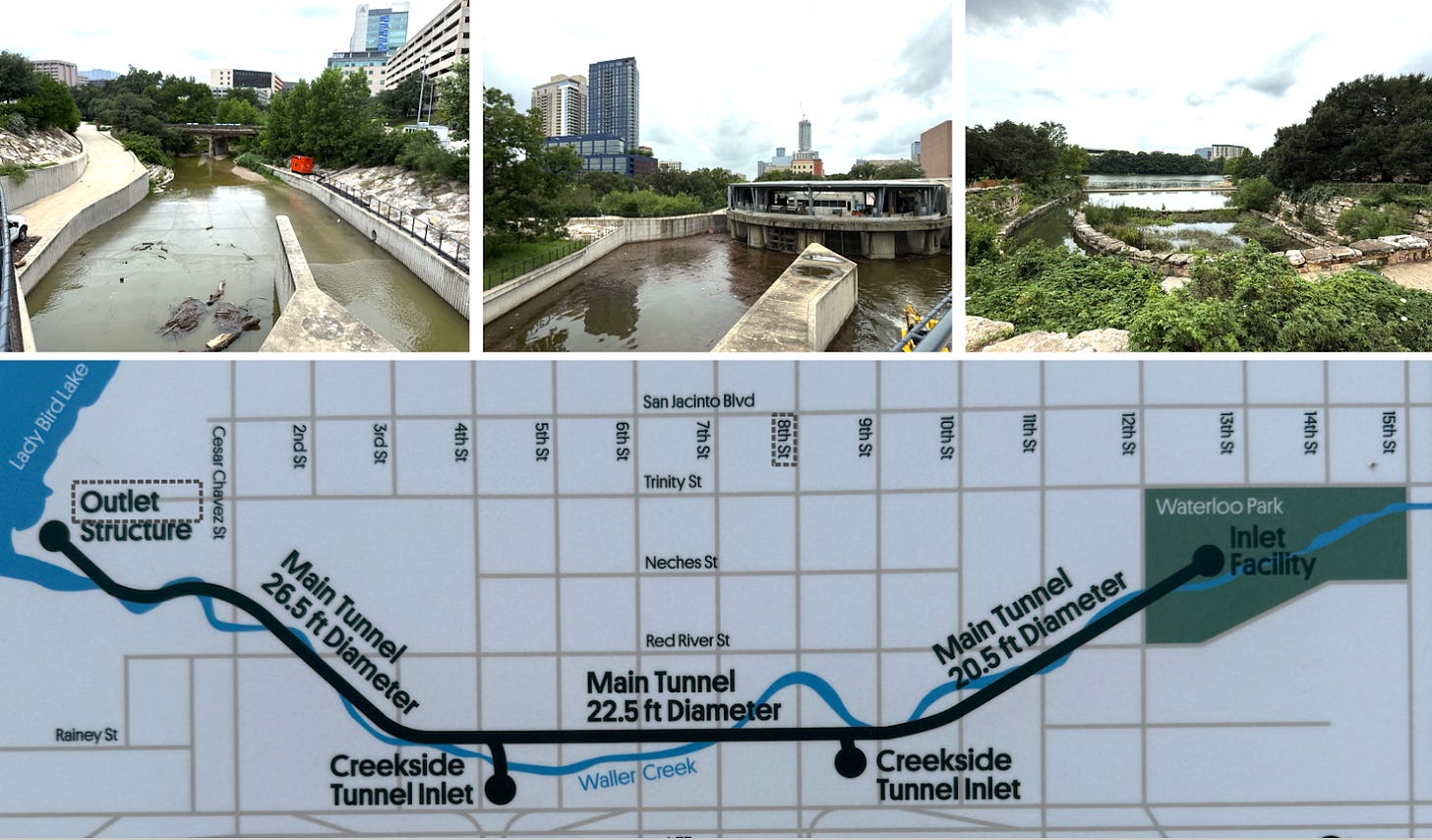

Creeks still pose a threat in Austin, even in downtown and other developed areas. On the west side, Shoal Creek regularly swells during major storms, flooding the nearby commercial district. On the east side, Waller Creek tells a different story. Once prone to chronic flooding and lined with neglected properties, it has been transformed by a mile-long underground tunnel that diverts floodwaters safely beneath downtown into the dammed Lady Bird Lake. This opened 28 acres of land for redevelopment and made way for the Waterloo Greenway—a 1.5-mile linear trail and park that restores riparian habitat, adds 11 acres of green space, and hosts the 5,000-seat Moody Amphitheater. The $163 million project was financed through a tax increment financing district—showing that when incentives align, cities can support climate resilience, civic spaces, and private development at the same time.

But not every part of the city could wait years—or find the funding—for projects like that. Without the means for more ambitious projects, Austin historically turned to zoning as a proxy for stormwater infrastructure, using land-use rules to shape how water moves through the city. In particular, the city imposed a zoning code that favored large-lot, single-family development, which covered most of the city in low-density zones on which you couldn’t build more than 40-45% of “impervious cover”—buildings, pavements, patios, pools, and other surfaces that don’t absorb water. Single-family lawns became the city’s primary strategy for dealing with stormwater runoff, which has been a roadblock for reforms aimed at further densification in the urban core.

The consequences of this policy were manifold. Because most of the city was zoned for large-lot homes, infill development was blocked—driving up prices and pushing growth outward. Those big lots required big lawns, and today one-third of Austin’s water goes to grass in the midst of near-constant drought. By limiting housing supply in the urban core, Austin’s policies helped push growth outward to the suburbs or unincorporated parts of the surrounding counties, fueling the familiar pattern of Texas sprawl. As lower-income residents found themselves also priced out of the suburbs, they sought out the only land they could afford. Often, that meant floodplains outside city limits, where counties have little power and few resources to manage risky development.

While Austin is not solely responsible for land-use patterns in the region, the city has begun to reverse course: legalizing more housing types, cutting minimum lot sizes, and lifting parking mandates. Meanwhile, state lawmakers have supercharged this effort with laws that curb the power of infill housing opponents and allow housing on underused commercial lots. Altogether, these reforms will create more affordable housing opportunities within the city—letting more people live where the infrastructure already exists to keep them safe.

Infill isn’t just an affordability strategy—it’s a climate resilience strategy. As Stephanie Nakhleh has argued, denser urban housing is green infrastructure—and building it quickly should be a green building standard. But Austin also needs a long-term stormwater management plan that doesn’t rely on single-family-only zoning as a substitute for infrastructure, perpetuating a cycle where we underbuild in the urban core while continuing to sprawl into more dangerous places on floodplains and in fire zones (the drought-stricken Hill Country also burns).

Which brings us back to Kerr County.

Not all of the devastation there was due to poor planning—this was an unprecedented storm, even by Hill Country standards. But the impact was worsened by the absence of local warning systems. Kerr County has no flood alert infrastructure—no sirens, no on-site alarms—because local taxpayers and officials declined to fund them. The National Weather Service did issue a regional flash flood warning on Thursday afternoon, but by the time it escalated to a catastrophic alert after 1 a.m., most campers at Camp Mystic were asleep in cabins without cell service or sirens to wake them. We can also ask why so many vulnerable places—including the century-old camp and clusters of housing—remain situated along a known high-risk floodplain.

Storms are natural, but risk assessment is man-made.

This isn’t about blame. But it is about choices: what infrastructure we decide to build, what risks we’re willing to take, what we can live with—and what we cannot.

This past legislative session, state lawmakers considered—but ultimately failed to pass—House Bill 13, which would have provided funding for local emergency warning systems and coordination protocols. Legislators balked at the half-billion-dollar price tag, but it wouldn’t have helped with this particular flood, anyway; the bill wouldn’t have taken effect until September 1 and its implementation would have unfolded over ten years. But its failure reflects a broader problem: Texas has consistently underinvested in the governance systems that could mitigate disasters like this one. For his part, Governor Abbott has added flood protection and relief to the agenda for a special legislative session he’s called, which, while too late for those who lost their lives last weekend, is still encouraging for those who remain.

Because Central Texas will flood again.

Last weekend’s floods show that nature will run its course, but Austin’s Waller Creek Tunnel and the LCRA are proof that we’re not powerless to change it. Flash floods are an ordinary part of the climate here—even before factoring in the effects of climate change. But extraordinary investments in public infrastructure have mitigated the damage these events cause in Austin, saving lives, reducing property damage, and creating public benefits that make life here not only possible—but livable. In an era dominated by short-range thinking, Austin’s past investments in flood management infrastructure are a striking example of what long-range urban climate resilience looks like in practice—it looks like the skyline of Downtown Austin, which wouldn’t exist without it.

We certainly cannot prevent every tragedy, but we can make choices about what we value, and what kind of world we want to live in. To survive in the Texas Hill Country, we need to engineer a better kind of life.

This is such a great piece, and so important. (And not just because I get a shoutout of course, but thank you for that.) It's infuriating to read about the factors that contributed to this tragedy, especially re: the warning system. The shortsightedness of legislators! In our town, county councilors have pushed and pushed for the Department of Energy to transfer tracts of virgin land in the wildland-urban interface for new single family homes... all to avoid having any infill mess up their views. This, after two devastating wildfires ripped through our area relatively recently. And Ruidoso, NM just had catastrophic flooding reminiscent of what happened in Kerr County ... but Ruidoso was far better prepared for it.

This is one time where Lake Travis being abnormally low because of drought was a blessing, there was plenty of room to take in all that water...