The Case for Single-Stair Buildings

How a Code Reform Could Make Housing More Affordable—Without Sacrificing Safety

Over my years in New York City, I lived in three former tenement buildings that had been converted into varying levels of “luxury” apartments—the nicest had granite countertops, stainless steel appliances, and exposed brick, while the worst at least had an in-unit bathroom. Each building sat on a narrow lot—25 to 44 feet wide and 100 feet deep—and housed between eight and thirty-five units across five or six floors. These were small apartments by most standards, but they offered something no other city could: relatively affordable rent in a walkable, transit-oriented, amenity-rich neighborhood in the greatest city in the world. And it was all made possible because each building only had a single stairway.

Along with Seattle and Honolulu, New York is the rare American city where small “single-stair” apartment buildings are legal.1 More cities and states—including Austin—are now proposing reforms to their building codes to allow safe, modern single-stair apartment buildings.

Why should you care about single-stair?

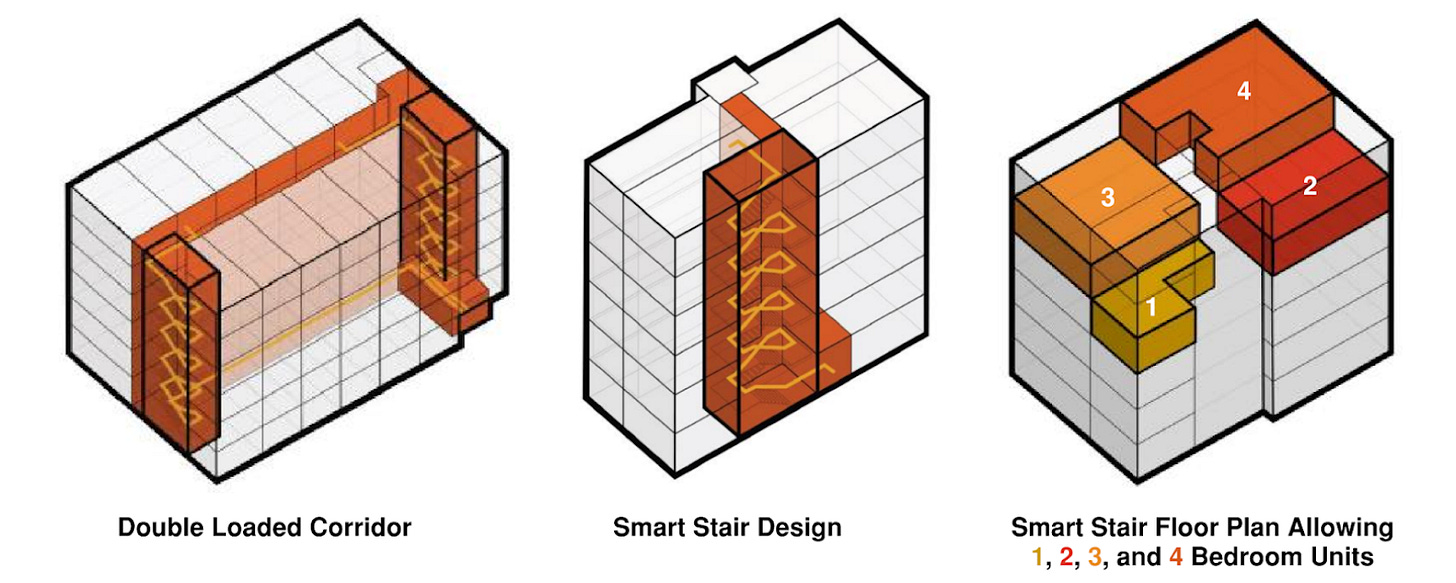

Under the International Building Code (IBC), a US-centric code adopted by most North American municipalities, single-stairway buildings are typically not allowed above three stories. Yet in much of the world—the “international” in IBC notwithstanding—single-stair buildings are the norm for mid-rise apartments. Instead in the US and Canada, most apartment buildings have “double-loaded” corridors: long hallways that bisect two rows of outward-facing apartments, with stairwells at either end. A result is that North American apartments tend to be long and dark, with windows only on one side. Aside from corner units, these are usually studios or one-bedrooms; tenants understandably want natural light in their bedrooms. Despite their ubiquity, these buildings are much-derided for their blandness and have come to symbolize the limitations of urban living. They’re one reason that “Cities Aren’t For Families.”

Small, single-stair apartment buildings are the “missing middle” of housing in American cities, offering more attainable homes to middle-income households. Historically, small apartment buildings were a common feature of residential neighborhoods across American cities. As a Pew study notes, although small- and medium-sized apartment buildings comprise 40% of the rental stock, “only 21% of all housing units built since 2000 in the U.S. have been in apartment buildings with two to 19 units.” Meanwhile, 42% of all new units built in the same timeframe are in buildings with 50 or more units. Zoning plays a role, but in most cities, the missing middle is missing because of building code regulations like dual-stairway requirements.

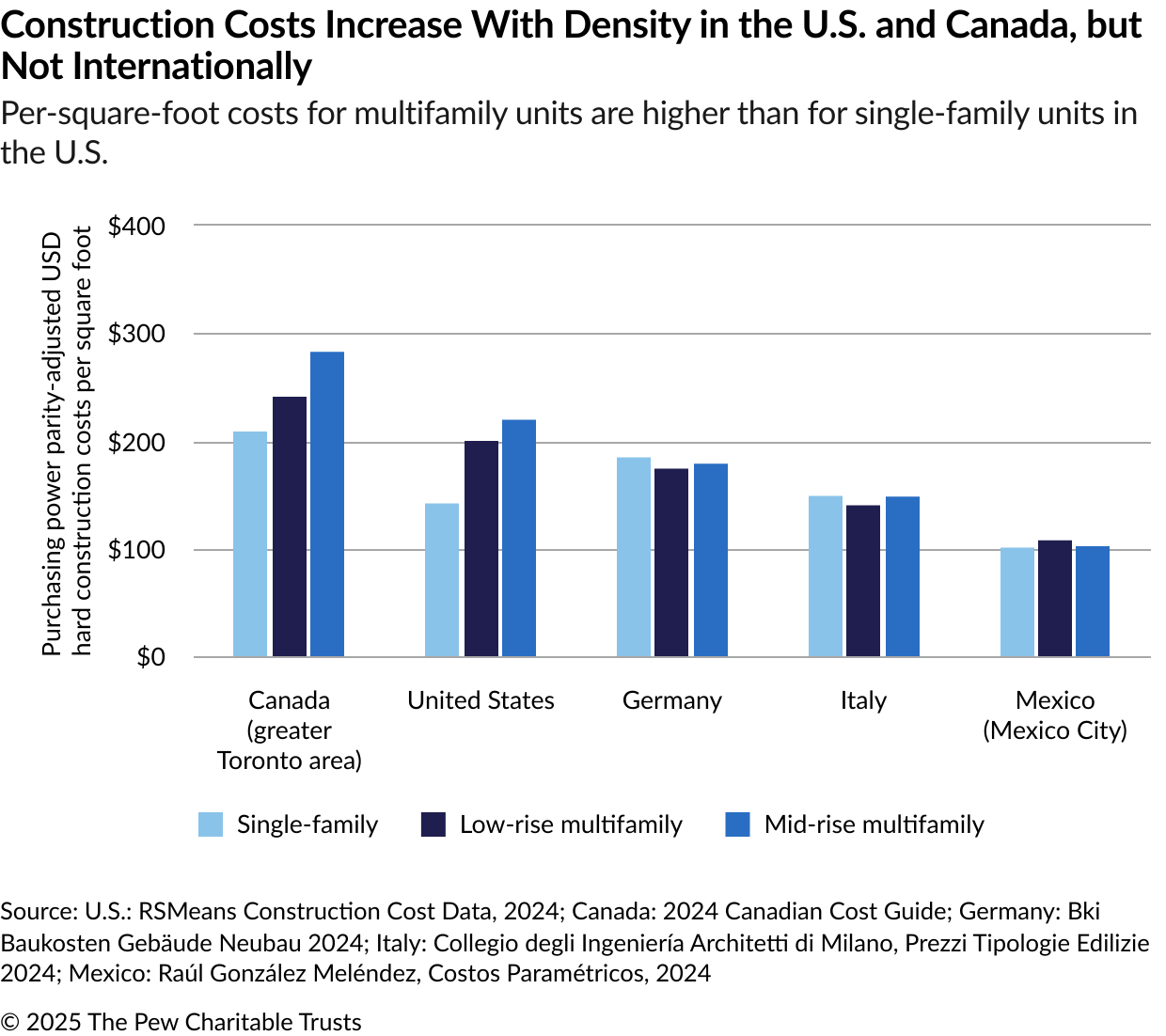

In Europe and much of Asia, single-stair buildings make more efficient use of space, allowing for better floor plans, ventilation, and natural light. With apartments clustered around a central landing instead of split by a hallway, these buildings often offer all-corner units that can accommodate two to three bedrooms—and urban families. According to Pew, the more efficient floor plates of single-stair buildings can reduce construction costs by 6% to 13% compared to similar dual-stairway buildings. Elsewhere in the world, construction costs remain consistent across residential building types. In the US, however, the IBC effectively penalizes density, pushing up costs as buildings get taller or house more units.

How did we come to impose more expensive and restrictive rules on our cities?

As Virginia Postrel describes, “Cities burn”—a fact driven home recently by the Los Angeles fires. Even there, the fires were contained to largely residential areas with wood-frame construction. Thanks to the use of less flammable construction materials like steel and concrete, fire suppression systems like sprinklers, and safer heating and cooking methods like electricity instead of open flames, downtowns rarely burn anymore. These upgrades add expense—but save lives and property.

Ironically, we’ve largely exempted single-family homes and duplexes from these same fire safety measures in 48 states. As I discussed in “The Upward Mobility Crisis,” early 20th-century reformers imposed higher safety standards on everything from triplexes to large apartment buildings to discourage apartment building. As Pew notes, US apartment buildings have improved in fire safety since 1980, while single-family homes and duplexes have not: “Buildings with sprinklers have lower fire death rates, lower firefighter and civilian injury rates, and lower property losses.” In reviewing more than a decade of fire data from New York City and Seattle, where single-stair buildings have been legal the longest, the study authors found no statistically significant difference in fire safety between single-stair and other types of apartment buildings. In fact, double-loaded corridors—which require longer evacuation routes and more easily trap smoke—may pose greater risk.

Today, Austin City Council will vote on adopting the 2024 International Building Code—as well as an amendment that would legalize single-stair buildings up to five stories. The Austin Fire Department opposes the amendment, echoing the National Association of State Fire Marshals, which claims that single-stair buildings are “contrary to decades of research and investigation validating the need for multiple exits.” Pew found no support for this claim: indeed, it’s common for 30 to 50 units to share a stairway in multiple-exit buildings, versus the 20-unit cap proposed in Austin. Austin Fire has also echoed the State Fire Marshals’ concerns that single-stair buildings are at risk from “active shooter situations”—a concern that bears no relation to where mass shootings actually take place in the United States. Valid concerns remain—about fire protection systems, corridor clutter, and fire department access, for instance—but they apply to all buildings regardless of stair count.

Pew finds that if single-stair buildings are: built with fire-safe materials; equipped with sprinklers, smoke detectors, and other fire suppression systems; limited in height (up to 75’, in reach of a fire ladder truck), floor area, unit count, and exit distance; and include smoke-control systems and other protections, then they are “at least as safe” as other types of apartment buildings. All such provisions are in the Austin proposal.

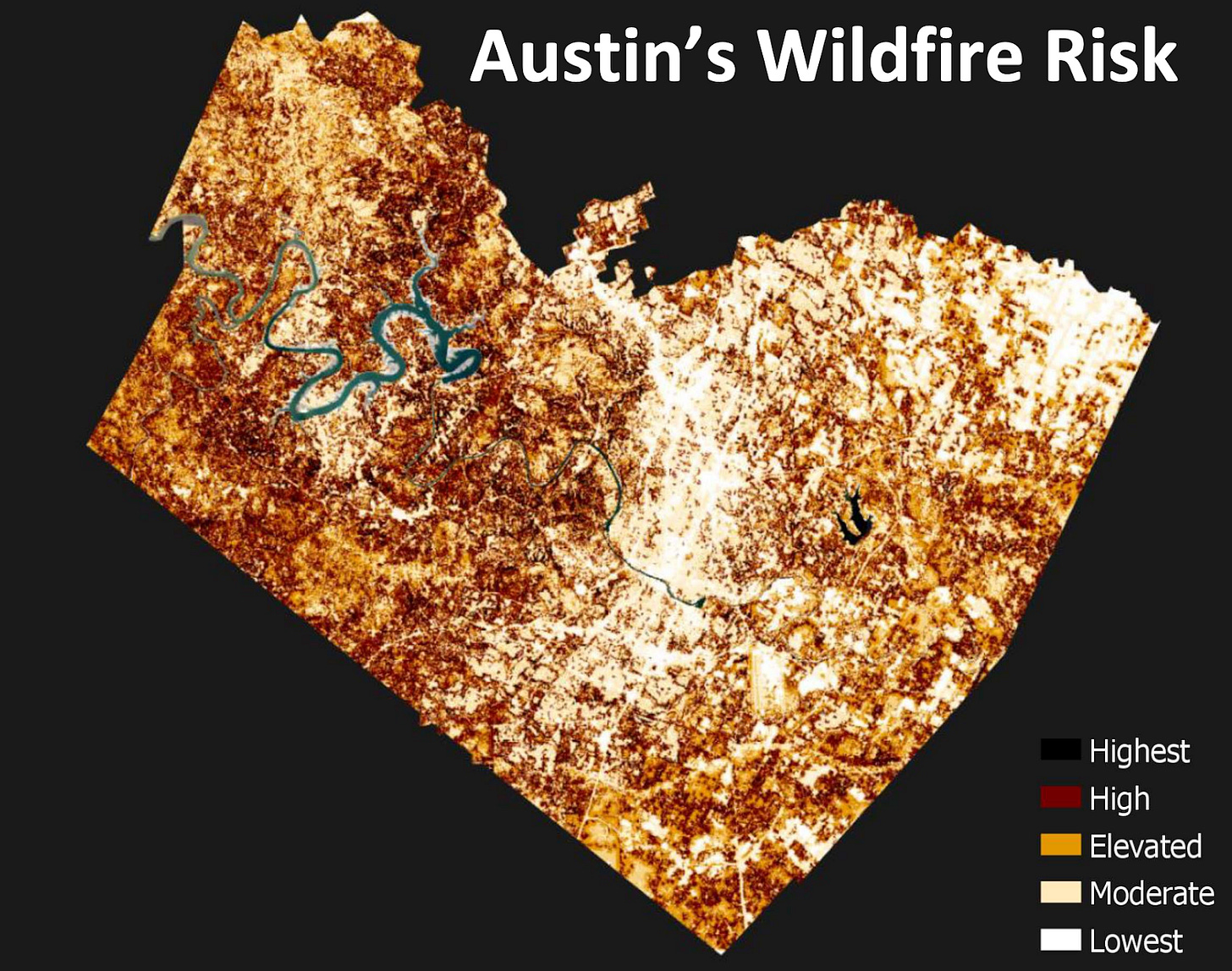

Incidentally, CoreLogic ranks Austin fifth nationally for wildfire risk—behind only four cities in Southern California. In response, Austin Fire is calling on the City Council to adopt a new wildfire risk map, one that would put 71% of Austin’s land parcels in a vulnerable zone, up from 38% ten years ago. The riskiest parts of the city are its least dense suburbs, which sprawled into the parched Hill Country. The dense urban core—shown as a white patch in the map below—is at the lowest risk.

This is all the more reason for fire officials to support single-stair buildings—especially in the central, high-opportunity neighborhoods where they’re most likely to be built. As an infill development tool, single-stair buildings could create more affordable homes for families close to jobs, amenities, schools, and services. Bringing more affordability to the central city reduces the need for the city to grow at the fringes, which strains the limited resources of our emergency services and increasingly puts lives at risk.

Single-stair reform is not a panacea, nor is it enough to unlock missing middle housing. Those buildings I lived in New York were all on lots that were 2,500 to 4,400 square feet in size. In Austin, we lowered the minimum lot size required to build a single-family home, but the minimum lot size required to build an apartment building is still 8,000 square feet, which precludes thousands of potential lots from redevelopment. That’s not the only roadblock. Austin limits unit count per acre, lot coverage, height, and total buildable area. Other rules mandate setbacks and elevator bulk. Austin eliminated minimum parking requirements, but that reform only goes so far while other code constraints remain.

Housing reform is a step-by-step process.

Nevertheless, many North American cities and states are now following the lead of New York, Seattle, and Honolulu. Tennessee passed a single-stair enabling act in 2024, allowing cities like Knoxville and Jackson to opt in; Nashville is considering it. British Columbia legalized single-stair reforms last year, and Ontario is exploring reform. Connecticut is developing revised code language, California commissioned a study, and New York State is looking to The City for inspiration. Meanwhile, “gay for housing” Governor Jared Polis has called on Colorado to embrace what he calls “smart stair” reform; Denver even held a Single-Stair Housing Challenge. And aside from Austin’s reforms, a single-stair bill has been introduced in the Texas legislature this session. Even fire-ravaged Los Angeles is entertaining a motion.

Legalizing single-stair buildings is an important step in unlocking affordable, family-friendly housing in high-opportunity neighborhoods across American cities. In New York and Seattle, they’ve provided safe, affordable homes for decades. In Austin, they offer a way to bring families and starter homes into desirable central neighborhoods. As affordability continues to plague working families, and as cities like Austin and Los Angeles grapple with increased fire risk, single-stair reform presents us with alternatives. We can keep sprawling outward into the fire-prone wilderness, exacerbating risk in the search for affordability—or we can build more intelligently in our safer central cities.

For the sake of safety and affordability, the only way is up.

Ironically, all three of these buildings would be illegal under New York’s current building code, since New York imposes a 2,000-square-foot limit on floor plates; there is a proposal to double this.

Santa Monica is also working on this. Getting a critical mass of cities going is key to overcoming fire department fear mongering.

What a fantastic piece to wake up to on the day we finally legalize these, the only way is up!