Everything’s in the Shitter

The Infrastructure of Public Order

Japan is famous for its infrastructure. A vast lattice of tubes and conduits spans the country, overhead and underfoot—a system engineered to keep a nation moving. In individual compartments, the system responds to your presence, announcing your arrival with a custom jingle: then, the doors open automatically, friendly icons and wayfinding guide first-time users, and the seats are warm in winter. One is never left waiting long, the journey is always comfortable, and when it’s over, everything is whisked away without a trace. This is a system designed for people who have to go.

I’m talking, of course, about Japan’s public toilets.

While in Japan a couple weeks ago, we took trains frequently around Tokyo and Kyoto. The trains were amazing, but what really impressed me were the bathrooms. No matter if we were riding the Shinkansen, commuter rail, or the metro, every station had free public restrooms available outside the gates and on most train platforms, above and below ground. Aside from the robotic toilet seats, the restrooms themselves were unremarkable. They were what bathrooms ought to be: gleaming, well-tended, free of trash, broken mirrors, grimy floors, nasty odors, and graffiti. This wasn’t the result of a national obsession with hygiene—many bathrooms annoyingly lacked hand dryers or paper towels—but rather a totally different set of assumptions about how public space should be used and valued.

Japan’s restrooms are not merely a nice public amenity but an essential part of Japan’s mobility system. The robo-toilets are cool and all, but it’s this basic technology of civic infrastructure that allows cities overflowing with millions of mobile people to feel clean, calm, and orderly. In Japan, when you’re on the go and you’ve got to go, you can just…keep going.

The American mind cannot comprehend this. Contrast this with the typical experience in a US city. Where public restrooms exist, they are either poorly kept or hard to reach. In Washington Square Park last summer, the restroom was so coated in grime that touching the sink felt like contamination—and there was no soap to wash it off. At Manhattan’s Hudson Yards around Christmas, I wandered through a multi-level warren of luxury boutiques in search of a bathroom. This is not only a New York problem, of course.1 While walking along Austin’s lakeside trail recently, I encountered a locked-up public toilet that stood like a relic of some lost civilization:

Look on my Public Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

The ruins of ancient cities reveal that sanitation was one of civilization’s first problems, and public toilets one of its earliest solutions. As Ben Wilson recounts in Metropolis, the builders of Mohenjo-Daro, located in what today is Pakistan, installed flush toilets in every household in the third millennium BC—“more than could be said for the same region of Pakistan today, 4,000 years later.” A mere two thousand years later, Rome built its famous fresh-water aqueducts and underground sewer system, along with a system of public toilets for the plebes. These communal toilets served a social function: not only did men air their thoughts in public while togas hid their privates, they would clean themselves with a communal “wiping thing,” a sponge attached to a stick called a tersorium. Roman Emperor Vespasian taxed the urine collected from public toilets for use in tanning, declaring “Pecunia non olet” (“Money does not stink”—but I bet the tersorium did).

While Tenochtitlan was providing regularly emptied public toilets for its citizens by the time the conquistadors arrived in 1519, the great industrialized cities of Europe wouldn’t begin to tackle the problem of sanitation at scale until the mid-19th century. Paris introduced the revolutionary pissoir, or open-air urinal, to its streets in 1830—only for most to be destroyed during the street-fighting of the July Revolution later that year. The pissoirs were reintroduced in 1843 as vespasiennes, in dubious honor of Emperor Vespasian, and by the 1930s the city had 1,230 public urinals. In the United Kingdom, George Jennings invented the first modern flush toilet and introduced the Victorians to public toilets, installing “monkey houses” in the Crystal Palace during the Great Exhibition of 1851. New York, Boston, and other cities experimented with European-style pissoirs in the mid-to-late-19th century, but ultimately abandoned them. In the early 20th century, cities including Cleveland, Denver, and Philadelphia built municipal “comfort stations” as part of a nationwide sanitation reform movement, providing access to women who often had to hold it in—or remain held back at home.

These facilities were not luxuries. They were explicit attempts to reduce street filth, improve public health, and bring order to rapidly growing cities.

For a time, Western cities treated public toilets as basic civic infrastructure, but that consensus eroded into the 20th century. From their 1930s height, Parisian pissoirs had declined to only 329 by 1966, and effectively to zero by the early 2000s—although Paris has since introduced modern, unisex public bathrooms called sanisettes. Austerity economics in the United Kingdom have led to the closure of nearly 700 public toilets since 2010, and 40% since 2004. In many other European cities, public restrooms still exist but are often behind a paywall—keeping them clean, staffed, and available. In the United States, municipal comfort stations faded after World War I. Pay toilets filled the gap, peaking at roughly 50,000 in the 1970s, only to disappear within a decade amid budget cuts and safety fears. Station bathrooms, ubiquitous in Japan, are rare here: most of the restrooms in New York City’s subway stations remain conspicuously padlocked.

Today, toilet access has been largely privatized along with every other aspect of American public life. The “public” restroom has retreated indoors, into bars and cafés and other private spaces where it has become a gated amenity “For Customers Only.” You must buy a coffee or burrito bowl for the golden ticket that unlocks the throne room.

Of course, the lack of public restrooms does not relieve the public of the need to go. Those who cannot afford a Caramel Ribbon Crunch Frappuccino® Blended Beverage take to the streets—not in the French manner, but by pissing (or worse) in alleys, in doorways, behind bushes, and under sidewalk sheds. Walking to work in San Francisco one bright morning, I encountered a woman popping a squat against a four-door sedan. She at least had the decency to apologize to me as my American mind tried to comprehend what it was seeing. Still, it’s hard to blame her for the dearth of public toilets in a city in which it costs $1.7 million to build one. Walking through the Lower East Side last summer, we saw two drunk dudes relieve themselves on the street outside of the bar they had just exited from. The bar had a bathroom, but they chose the street.

This is the difference: we have come to accept disorder on our streets—but instead of restoring order, we reject the public infrastructure where disorder occurs.

Public order requires not only institutions but infrastructure—and, where necessary, enforcement. A ban on littering is mostly garbage in the absence of a trash can.2 A posted speed limit is merely a suggestion in the absence of traffic cops. In high-trust societies like Japan, order is embedded in cultural norms and maintained by the people themselves. In America, we may require attendants, security, or police to keep public spaces truly public. Here, norms have frayed and shared responsibility has eroded, so we can no longer rely on informal self-governance in our Age of Assholes. Rebuilding basic civic infrastructure is one way to begin restoring it.

Public toilets make this visible. Where they are built and maintained, predictable human needs are met in designated spaces; where they are absent or neglected, those needs spill into the street and degrade the public realm. Disorder, quite literally, flows downhill.

The existence of free, safe, clean public restrooms is emblematic of Japan’s approach to urbanism: the city is understood as a shared civic space, and citizens are expected to behave accordingly. Order is the default, not the exception. In American cities, we are still arguing over who the city is for. It is contested ground, and order is negotiable. We permit people to misuse public restrooms for illegal, unsafe, and unhygienic purposes—often because policy failures elsewhere have left them with nowhere else to go. But when our most basic civic infrastructure is repurposed as a social safety net, we don’t just fail the most vulnerable. We effectively exile everyone else from the public realm.

In the American city, the “public” restroom has been largely purged from the public square—and so we have excluded much of the public from ostensibly public places.

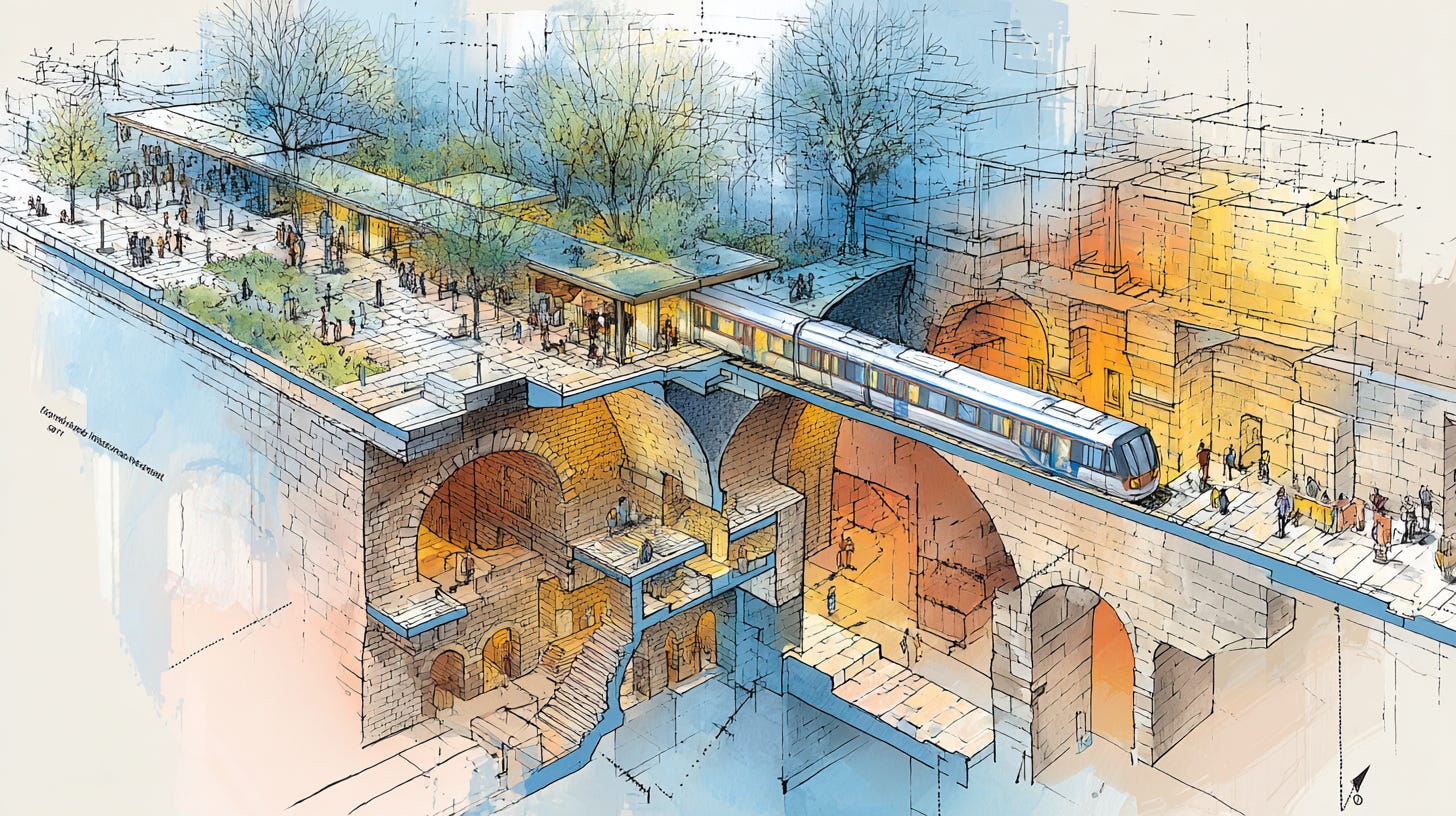

If the Romans left behind working aqueducts and marble latrines as markers of their civilization, the Japanese have given posterity bullet trains and robo-toilets at scale. Japanese cities are built to not only connect people, but also to accommodate them along the way. Clean, safe, public restrooms are as much a sign of civilization as a high-speed train network, revealing whether a society can maintain order in the most ordinary spaces.

A society that cannot maintain a public restroom cannot maintain public order. A society that cannot maintain public order cannot maintain its cities.

Ultimately, civilization is not measured by the heights of city spires or the speed of transit: it’s in the shitter.

Emperor Vespasian taxed public urinals because he understood that infrastructure does not fund itself. If you value this work and want to see more of it, consider becoming a paid member. I’ll continue publishing free essays, but more of my writing will be reserved for paid subscribers starting in March. Pecunia non olet!

To be fair to New York, Manhattan’s Bryant Park features a restroom so well-tended—complete with fresh flowers, classical music, and full-time attendants—that it has won national awards.

Remarkably, Japan achieves this same level of order regarding litter despite a near-total absence of public trash cans.

Great piece. Enforcement really only works when infrastructure exists to make enforcement necessary in rare cases. Hard to enforce speed limits when the roads are so wide that many people speed. Hard to enforce bathroom norms when there are so few restrooms

Japan’s restrooms and associated social norms sound like the platonic ideal, but I’d happily take ubiquitous European pay toilets over nonexistent American toilets

I live in the Pacific Northwest near Seattle. Many public toilets range from off-putting to outright disgusting. Some businesses have taken to locking their restrooms; in some cases you have to ask for a code, in others a staff member must let you in. Some people turn tricks and shoot up in public restrooms. In public (obviously not in businesses) I favor pay toilets. That way I could be assured of cleanliness, at least I hope so. However, especially on the part of the "homeless," there is such a sense of entitlement, there would be outrage and probably damage to the structures. Plus it would by hugely unpalatable politically. I think a cultural change would be necessary in my part of the country before we could address cleaner, safer toilets. I agree with what you said about basic civic infrastructure being viewed as a social safety net, which is sad, and doesn't help anyone.