Reboot the City

Restarting the Engine of Urban Progress

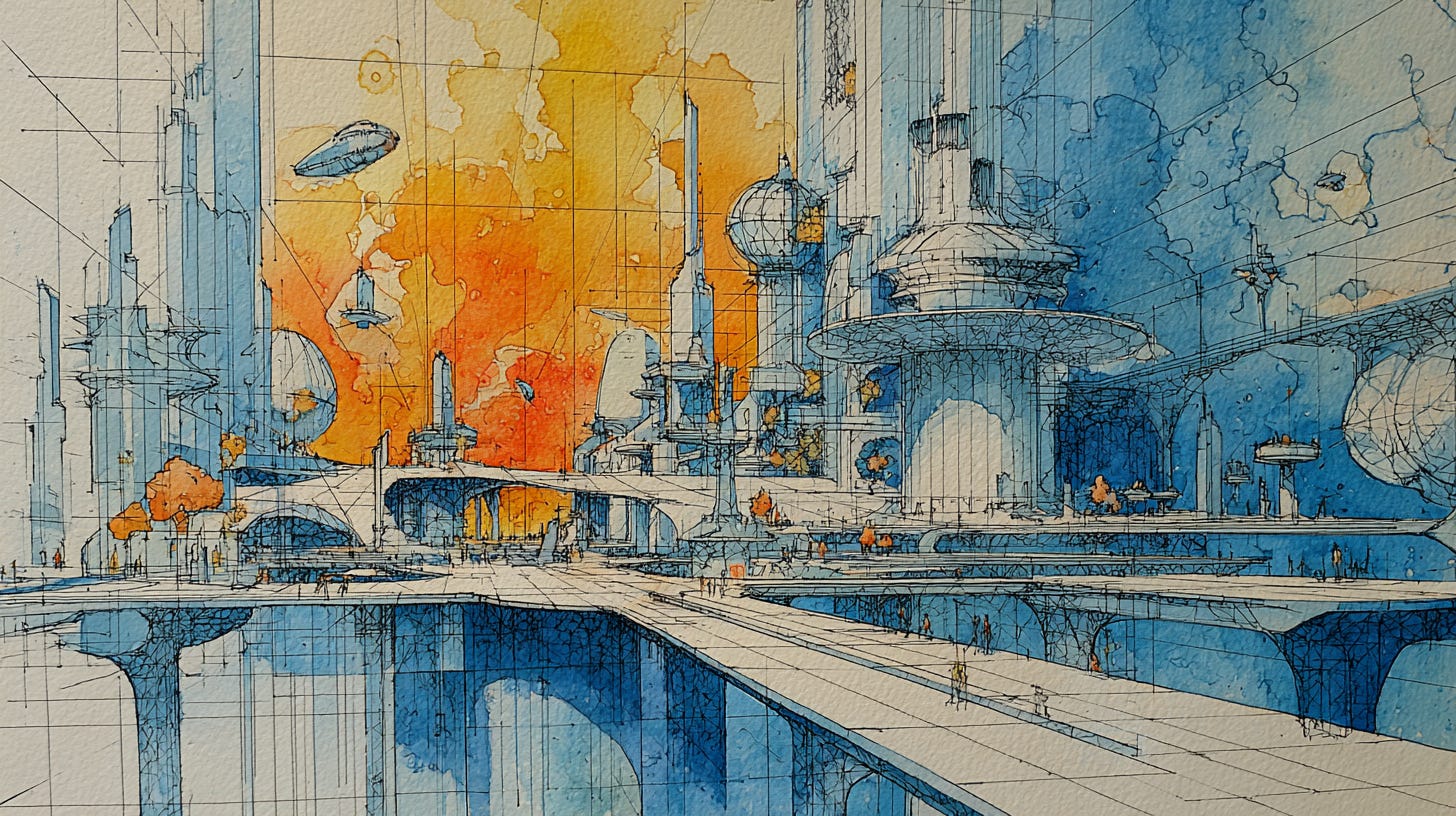

When General Motors unveiled the Futurama exhibit at the 1939 World’s Fair, millions encountered for the first time a vision of urban life offering a clean break with the past. Gone were the tenements, the snarled streets, the creaking infrastructure of the industrial city. In its place would rise the City of Tomorrow, one in which cars zoomed along linear, multilane highways carved through towering downtowns. In the future, everything—and everyone—was on the move, and even this vision was but one stop on the path to progress. Flying cars, glass domes, and self-cleaning sidewalks—the City of Tomorrow was not only coming but already under construction.

Nobody lives in the City of Tomorrow today.

It’s not because it wasn’t built. GM’s vision of the car-centric city was faithfully executed across America, putting historic downtowns on the chopping block as urban renewal leveled the City of Yesterday. It turned out that the City of Tomorrow was less glamorous in practice than promised: alienating towers set amidst vast fields of parking lots, long commutes, so much noise and smog. The arrival of the combustion engine in downtown brought outward mobility to the masses—and choked the upward mobility engine that had built America’s urban middle class.

The mistake that the visionaries of the mid-20th century made was not one of malice or pipe dreams. It was that they misunderstood what was wrong. They looked at shabby cities full of historic buildings and factories, built around horse-drawn carriages and pedestrians, and saw only inefficiency and obsolescence—the technology of the past. But the problems facing the City of Yesterday were not inherently about physical technology—indeed, the technological “fixes” ultimately didn’t work. They built the hardware of the future but left the civic software untouched—and it was a software problem that cities were facing.

Cities are the platforms—the hardware and software—through which we realize human flourishing at scale. When the hardware or software system stalls, cities stop generating mobility—social, economic, and physical alike. If the physical city is the hardware of civilization on which human life runs, then its operating system is the civic order itself: law, governance, and culture.

Law sets the city’s rules of coexistence—what people are free to do, what they may not, and how they relate to one another. It’s a system of rights and constraints. It grants permissions to build, start businesses, assemble, and protest—regulated by codes and permitting systems—and it sets limits harm via restrictions on pollution, violence, and exploitation.

Governance operates through an institutional architecture that translates law into action. It includes embodied institutions—courts, councils, agencies, departments, police—and procedural institutions such as budgeting, planning, procurement, the administration of justice. These institutions and processes are how cities keep the lights on and the streets safe.

Finally, culture shapes how people experience and interact with the city. It establishes defaults—what residents assume government does or doesn’t do. Do potholes get paved quickly, should new housing “fit in”? Culture also shapes behavior: whether people volunteer, engage in philanthropy, attend town halls, or only vote every few years.

Urban progress depends on all three aspects working together. This operating system doesn’t dictate what people create or how they live; those are outputs. Its job is to make such activity possible at scale. Yet when law, governance, and culture fall out of sync, the city’s user interface becomes counterintuitive and opaque—a vehicle not of civic empowerment, but of frustration, complaint, stagnation.

By the mid-20th century, the American urban operating system was failing. The law had become byzantine and cumbersome, throttling housing development, small business creation, and economic vitality. Governance reflected a technocratic faith in centralized control—one that hardened into bureaucracy, becoming sclerotic, occasionally corrupt, and mired in process. Partly in response, urban culture became mired in a Culture of No—a politics of paralysis disguised as virtue. Cities made some upgrades in the late 20th century, but the City of Today still runs on outdated software.

Our housing shortage results not from a dearth of land or the right construction techniques—but because exclusionary zoning regimes and discretionary approval processes make it incredibly difficult to build. Transit systems are slow and inefficient because we prioritize the wrong things: outdated union work rules over automation, or environmental proceduralism over environmentally-friendly solutions. City services are unresponsive because bureaucratic procurement processes add delays and cost overruns, ensuring when new technologies are finally adopted, they’re already obsolete. This is not to say we don’t need better hardware—but it’s subject to the same parameters of our broken operating system. Progress begins where permission becomes possible, but our urban operating systems are built to say “no.”

Our cities don’t need an upgrade—they need a reboot.

If the glamorized view of midcentury progress was benign, the turn against it was intentionally less so. Speaking as much to cities as to society at large, Jason Crawford writes:

Our societal sclerosis is partly the result of deliberate sabotage, motivated by the romantic backlash against progress: the view of material progress as a “destructive engine” and the goal of controlling it, slowing it down, or stopping it altogether.

But it was also the result of “institutional senescence.” Even without bad actors or anti-progress ideologues, institutions naturally grow old and die unless they’re actively maintained. Progress isn’t self-sustaining—it requires continuous cultural and institutional renewal.

Urban progress isn’t about growth or renewal for its own sake. It’s about expanding the capacity of people to build, connect, and create together. It’s measured not only by the height of the skyline or the speed of a bus, but by the city’s ability to adapt to evolving human needs. It’s whether cities make it easier—not harder—to live, and to build families, businesses, and civic organizations. Urban progress is about whether the civic operating system makes it possible for human flourishing.

Progress happens only where laws, regulations, and processes are predictable, legible, and low-friction—where the default setting is “yes.” What we need isn’t another layer of code but a full system update.

It’s easier to change the law than an institution, and easier to change an institution than the culture—but all can change over time. We can persist in the stagnating City of Today, pine for a pale imitation of the City of Yesterday, or choose the kind of progress that makes the City of Tomorrow tangible for real people. The technology of the City of Tomorrow is already here; what we need is to give ourselves permission to build it.

What does urban progress look like to you?

We often understate how much cultural change it will take to move the needle on all these other factors. The cultural defaults can be very stubborn.

Amen to all of this!