The Slumless City

How Urban Renewal Nearly Unmade New Haven

Flying over Europe during World War II, Ed Logue came to appreciate the urban form from above. Endless hours floating in the “great glass bubble” of a cockpit taught him how to “read” cities—“the best possible city planning training,” he later claimed.” With a bird’s-eye view of the historic cities below, he saw that cities comprised “parts of a well-calibrated machine,” and he imagined what they might look like if they were organized into more idealized, distinct zones.1

From the great glass bubble of his US Air Force plane, he would then drop bombs on the cities below.

Logue would take this urban inspiration and begin applying it to American cities at scale, starting in New Haven, Conn., where Mayor Dick Lee appointed him administrator of the New Haven Redevelopment Agency (NHRA) in 1955. Together, Lee and Logue would embark on a massive renewal plan that would make New Haven “the model city of urban renewal, a laboratory for salvaging urban America.”2 Altogether, their works would touch “one-third of New Haven’s land area—or approximately 2,400 acres—and one-half of its population.” They demolished 5,000 low-income housing units, rehabbed 9,000 homes, built 2,600 publicly-subsidized units, and displaced upwards of 30,000 people—many of whom had nowhere else to go.

The thing you have to know is, just as the allies understood that the destruction of Europe’s Nazi-occupied cities was necessary to win the war, Lee, Logue, and other modernists of the urban renewal era thought they had to destroy the city in order to save it. What they failed to understand was that urban renewal was anti-urban—it undermined the street life, density, and diversity that make cities thrive.

They say that hell is paved with good intentions. For the victims of urban renewal, hell was simply paved.

Yet it was wildly popular at the start.

In 1910, Cass Gilbert and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. projected a booming New Haven of 400,000 people by 1950. Instead, by the 1920s, the city was already in decline as manufacturing faltered and shipping moved elsewhere. The city’s population would instead peak at 164,443 in 1950, but by then middle-class, mostly white residents had been fleeing to the burgeoning suburbs, replaced by poorer European immigrants and black migrants escaping the South.

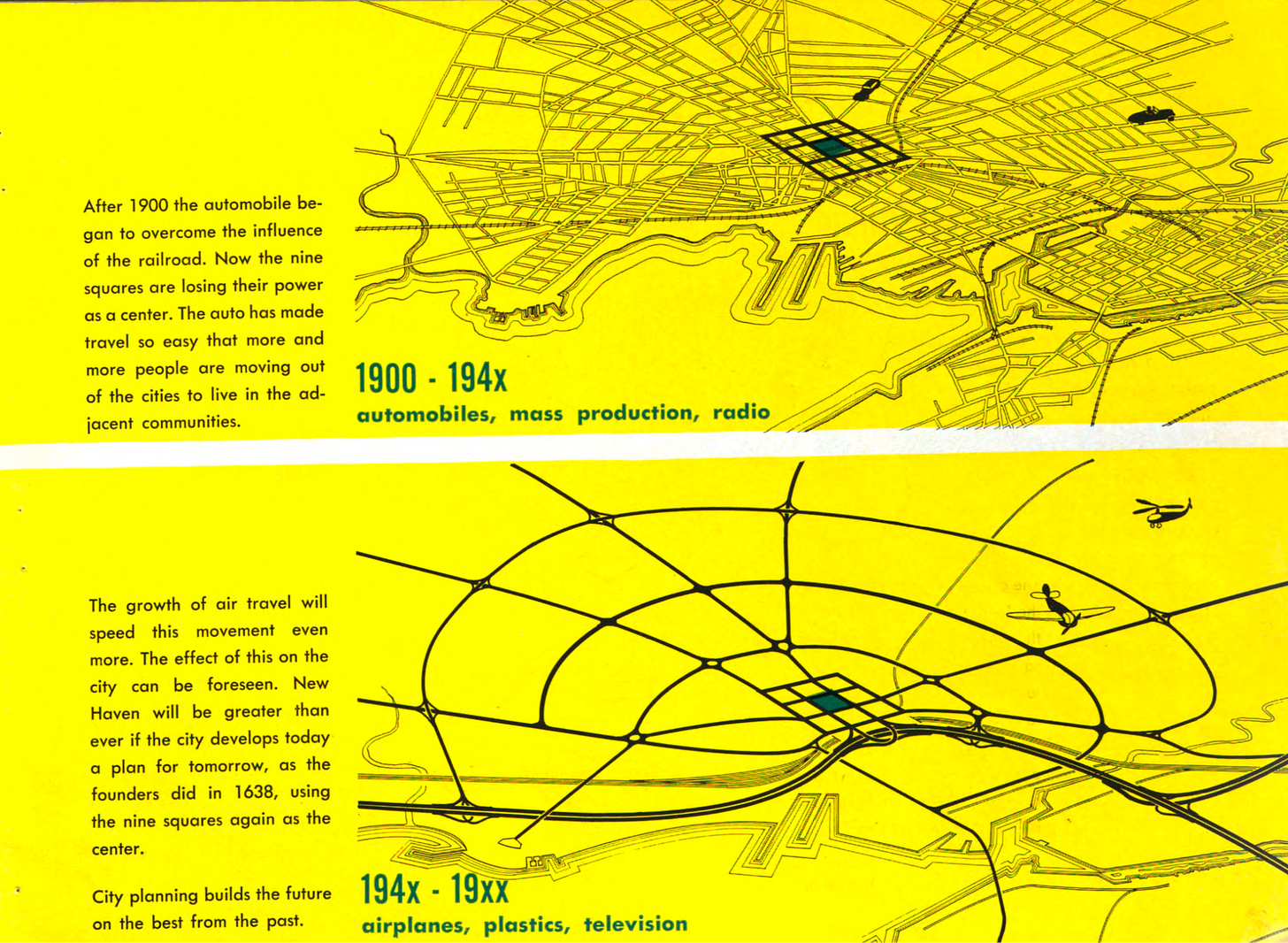

Although the war gave the city a temporary lift, city leaders grew concerned as historic neighborhoods deteriorated into so-called slums. So in 1944, before “our boys” returned from the battlefields, they announced “Tomorrow Is Here” in a pamphlet written by Maurice Rotival, a French-born planner and Yale professor influenced by Le Corbusier. They asked, “Why are people moving out of New Haven?”

The answer was “suburbanization”—and so Rotival and other city planners determined that the only way to fight the suburbs was to make New Haven more like the suburbs themselves. As Mayor Lee said, New Haven would embark on a “blitz of demolition” to become the nation’s first “slumless city.”

For Lee and Logue, slum clearance was a moral imperative—slums were “evil” and rebuilding them was essential to revitalizing the city. Their timing could not have been better: New Haven became the leading recipient of federal urban renewal dollars on a per capita basis, almost three times that of the next highest city, Newark—nearly $1 billion in today’s dollars.

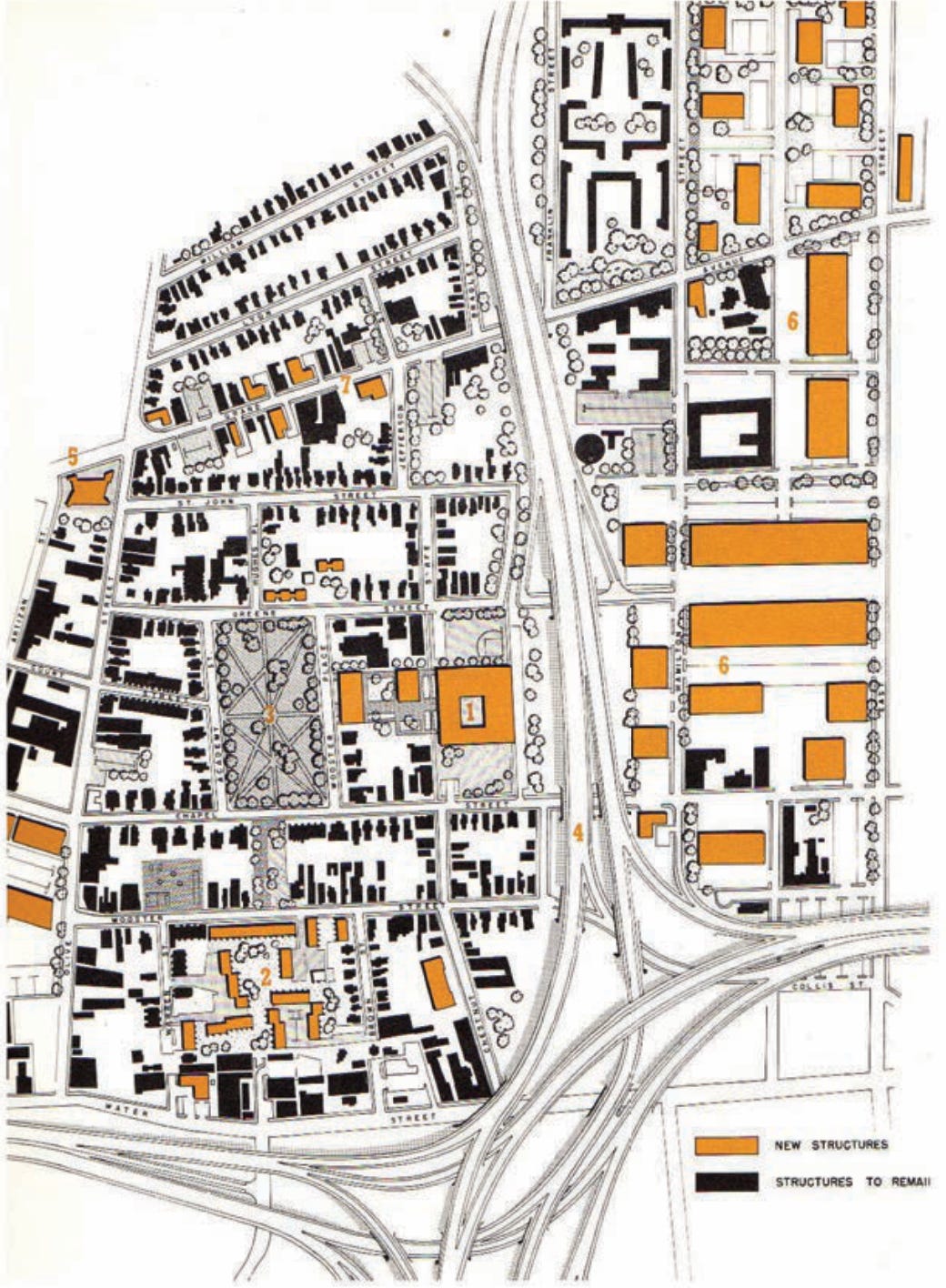

Logue’s NHRA followed a plan inspired by Rotival, who, like his mentor Le Corbusier, believed the great sin of cities was the mixing of uses. Le Corbusier’s “scientific” ideal called for separating homes from commerce and carving high-speed traffic lanes through the city. New Haven’s leaders embraced this, blaming mixed uses for creating slums without consideration of the affordability or vitality those neighborhoods provided.

As Yale art historian Vincent Scully observed, the modernist goal was “to wipe the present clean of the past, to sweep it pure of contaminating objects…We would brook no compromise.” Armed with near-dictatorial powers, Logue would do to New Haven what his bombs had done to the cities of Europe.

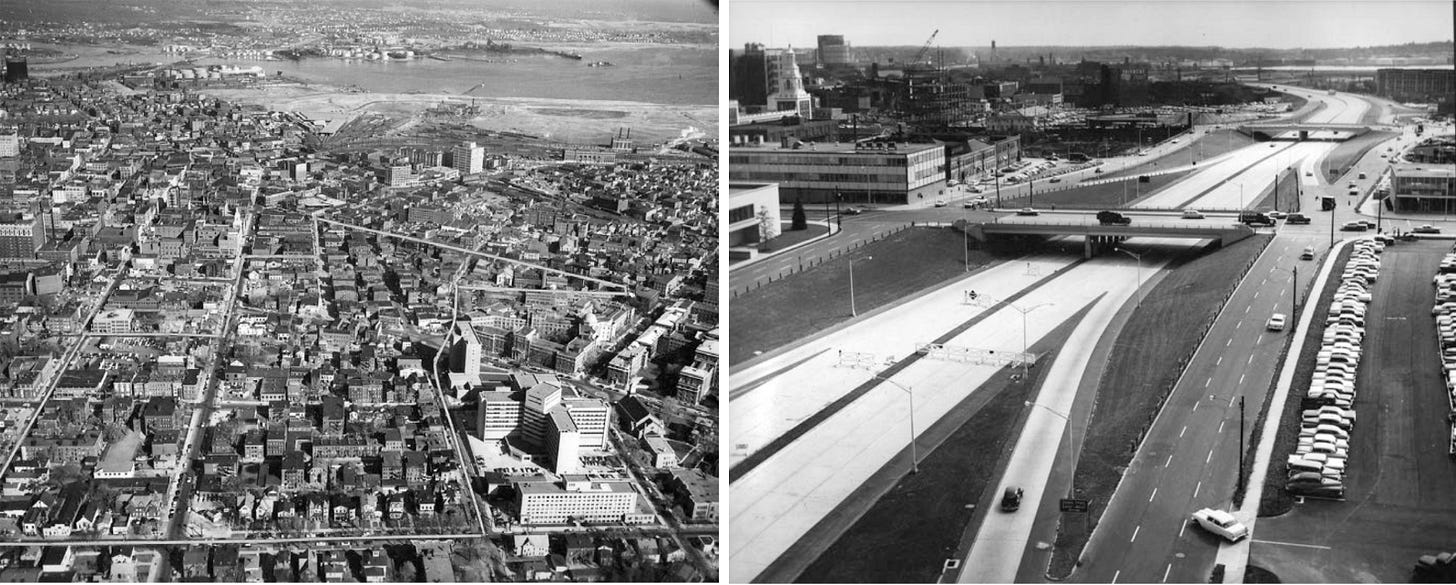

The Oak Street Connector was the centerpiece of New Haven’s urban renewal program. A short highway spur meant to speed suburban commuters into downtown, it cut a 300-foot-wide trench through the Oak Street neighborhood, demolishing homes, houses of worship, immigrant halls, and the city’s “film row,” displacing 3,000 black and immigrant residents. Crowded and dilapidated as they were, these “slums” provided affordable housing near downtown in which the poor could establish themselves before moving to more stable working-class communities. As one displaced resident recalled: “There used to be people—thousands of real, live, people living on Oak Street. It wasn’t the classiest place in town, but it was home.” Instead, it became a “speedway to the future,” lined with commuter offices turned away from the street. What Rotival had called a “necessary catalyst for community development” instead cut the city off from itself.

The solution to this problem was more urban renewal.

Looking at the old downtown business district, with its “standard fare of dated stores, modest personal services, and cheap luncheonettes,” Lee and Logue didn’t see the economic and employment opportunities that these mostly family-owned-and-operated businesses provided; they saw the “remnant of the provincial past, not a path to a modern future.” They replaced fine-grained street retail with a car-oriented superblock, encompassing a hotel, offices, and the Chapel Square Mall, copying the suburban template with interior courts, blank exterior walls, and attached parking. By containing shoppers inside, it starved the surrounding streets and killed hundreds of businesses that had provided families with opportunities for upward mobility. Urban renewal was killing the old city faster than the new one could be built.

New Haven’s residential renewal program reflected both the modernist zeal for “towers in the park” as well as a new appreciation for rehabilitation, enabled by changes in federal legislation. In Wooster Square, NHRA rehabilitated old row homes while building a new community school. Their efforts stabilized the neighborhood instead of erasing it—though planners bowed to white residents’ demands to build a new highway across the black section of the neighborhood. In other parts of the city, the old model prevailed: blocks of three-deckers and mixed-use streets were razed for public housing complexes surrounded by alienating open space. The goal, as The New Haven Register described it, was the “total obliteration of the ghetto image.”

Instead, reality obliterated the idealism of the urban renewers.

Logue and Lee had sincerely believed that their urban renewal program would create a “slumless” New Haven that was more racially integrated. Even New Haven’s black residents were enthusiastic supporters of urban renewal at the outset, seeing it as part of an integrationist agenda that would open up more opportunities for black people and eliminate inequities in wealth and shelter.

The reality was starkly different. While often derided as “Negro removal,” urban renewal in New Haven left “low-income residents with many years of evictions and exorbitant rents” as they were shunted from one part of town to the next. Meanwhile, it only hastened white flight: middle-class white people left the city at five times the rate of non-white people, “who could not afford—and were not welcome in—white suburbs.” Non-white people entered public housing three times as frequently as white people, while displaced white people—more likely to have been homeowners—used their compensation to buy elsewhere. The result was that urban renewal increased segregation, producing the “near-total Africanization of public housing.”

A demoralized Logue later acknowledged that “the unwillingness of most white Americans to share their neighborhoods with non-whites” was what generated slum conditions—which makes the failure of white and black leaders alike to appreciate “what was lost when neighborhoods were destroyed and intimate social bonds were broken” all the more tragic.

But, initially at least, urban renewal was what the people wanted. They just didn’t know what it meant.

It’s easy, looking upon the great works of the urban renewers with the benefit of hindsight, to despair. But midcentury renewal must be situated in its cultural context. In the postwar era, city planners were dealing with a new problem, the rapid suburbanization that would drain populations from city centers, and the miracle technology that was ushering in a bold, modernist future. Nearly everyone believed that capital-P Progress was being delivered to the masses by four wheels and a combustion engine. From World’s Fairs to magazine ads, Americans heard the same message: the future belonged to the car. To argue otherwise was against the mainstream. Indeed, New Haven’s renewers argued that opposing the Oak Street Connector meant “championing crime, disease, juvenile delinquency and higher taxes.”

Logue and Lee saw themselves as reformers in the Progressive tradition—and they measured their progress by the buildings they destroyed and by the people they displaced. Yale’s involvement lent an official imprimatur: its campus became a national modernist showcase with new buildings by Saarinen and Kahn, while its deans sat on Mayor Lee’s urban renewal commissions, conferring prestige on the city’s vision. The program of urban renewal, including slum clearance and highway construction, was federally funded, bipartisan, and broadly supported by the public. Despite their opposing politics, the “Master Rebuilder” Ed Logue is often compared to New York’s “Master Builder” Robert Moses, because both men were undertaking what they saw as a massive effort to save their respective cities.

Neither Logue nor Moses created the zeitgeist—but both were effective agents of the demolition blitz.

By the mid-1960s, the consensus cracked: a backlash was already well underway as residents, community activists, and preservationists fought highway expansions and slum clearance. By 1968, the magazine Progressive Architecture—which had championed much of New Haven’s efforts—was now questioning whether urban renewal produced the very slums it sought to eradicate. Logue himself came to regret the early “bulldozer urban renewal,” and, while sparring with Jane Jacobs, edged toward her insight that “new ideas need old buildings.” Even as later urban renewal efforts shifted more toward rehabilitation, Logue also sensed a deeper conundrum: it simply wasn’t possible to renew a city in the absence of economic and civic revitalization.

Mayor Lee had proclaimed to his constituents, “We are taking the town out of the eighteenth century and projecting it into the twenty-first.” By 1970, New Haven’s population had fallen to 137,707, just 39% of the metro area—down from 81% in 1920. Median incomes had dropped to only two-thirds of the metro area. By the time the urban renewal era ended, New Haven was smaller, poorer, and more racially segregated. In contrast to Maurice Rotival’s promise that “tomorrow is here,” the midcentury urban renewers perpetuated slum conditions and delayed the arrival of a better future for decades to come.

New Haven’s experiment in urban renewal failed not because it was poorly executed, but because it was ideologically anti-urban.

And by the 1980s, it was falling apart.

The Chapel Square Mall briefly drew anchors like Macy’s but soon struggled, hollowing out street life and accelerating downtown’s decline; by the 1990s it had closed and was later converted into apartments. The Veterans Coliseum, another car-oriented monolith along the Oak Street Connector, had deteriorated so much by 1987 that city leaders contemplated demolition—only 15 years after its construction.3 By the 2010s, city leadership sought to undo the Connector’s damage by restoring the street grid, reconnecting neighborhoods, and reclaiming land.

Is New Haven any closer to its dream of a “slumless city” today?

Though it has taken new leaders in the twenty-first century to reconsider the policies of the twentieth, the early results are promising: today, after reaching a modern low of 123,626 people in 2000, New Haven’s population has grown to more than 137,000—and downtown is now one of the fasting growing neighborhoods in the city. Its recent leadership seems committed to repairing the harms of the renewal era, including supporting new development that embraces the street and walkability, as well as infrastructure projects that benefit modes other than automobiles. This is real progress—but it will take generations to rebuild what the urban renewers destroyed in theirs. Unlike their glass-bubble aerial visions, that work can only begin from the street up.

Tomorrow might not yet be here in New Haven—but it seems a lot closer than it once was.

Related Reading

Desegregate Connecticut

In 2000, my hometown of Wallingford had the dubious distinction of being the only one of Connecticut’s 169 towns and cities not to fully close its municipal doors on Martin Luther King Day. What began as a labor dispute over the holiday in this town of 44,000 people morphed into a national racial flashpoint, drawing marches by the Ku Klux Klan and Jesse…

All quotations and figures, unless otherwise specified, are from Saving America’s Cities: Ed Logue and the Struggle to Renew Urban America in the Suburban Age by Lizabeth Cohen and “Tomorrow is Here: New Haven and the Modern Movement” by Rachel D. Carley of the New Haven Preservation Trust.

I spent much of last week in New Haven attending YIMBYtown, which was held at the Omni Hotel, part of the Chapel Square Mall urban renewal project.

It was demolished in 2007 and remained a parking lot until a portion was redeveloped into an apartment complex.

That "Tomorrow Is Here” pamphlet hurts the heart...

A hella lot of damage to people’s lives was done in the name of renewal. Thad argues for more modesty and thoughtfulness in planning today.