We’re All Experiencing Homelessness

A Visible Crisis, Willful Blindness, and the City That Saw a Solution

When I lived in San Francisco, my apartment in the Mission District faced a small church, where a few homeless people regularly camped. It was mostly a minor nuisance—until the pandemic, when the encampment grew to occupy the entire block. The smell became unbearable, needles commonplace. The city responded not with housing, but with a porta-potty, a handwashing station, and eventually an attendant—until someone was shot there one night in the long summer of 2020. Only then did they make a half-hearted effort to clean it up.

I wish I could say that was the worst of it. On my daily walk to the Montessori school I managed near City Hall, I’d pass clusters of drugged-out or passed-out people lying on sidewalks or stumbling into traffic, paraphernalia scattered amid piles of human feces and shards of glass from smashed car windows. At the school, we regularly had to deal with break-ins from homeless people.

What I saw was not the entirety of homelessness in San Francisco. It was the visible part—and that visibility, more than the reality, shapes public opinion and drives our politics.

This is the “experience of homelessness” that animates the Trump Administration's recent executive order, Ending Crime and Disorder on America’s Streets. It directs federal agencies to crack down on urban camping, public drug use, and vagrancy, while promoting involuntary commitment for those with serious mental illness or addiction. It ties federal grants to visible enforcement and calls for ending “Housing First” and harm reduction programs.1 Supporters consider it “a much-needed course correction,” while critics argue that it criminalizes homelessness—a policy of “gulag first.”

Given the administration’s approach to the border—where Democrats long downplayed the crisis—no one should be surprised by a similarly heavy-handed response to homelessness. By closing the door on abundant housing and real interventions, urban progressives opened the door to this. Understandably, many people are tired of the disorder on city streets—and at a humanitarian level, they’re right to be. People should not be camping out in public spaces—not only because it degrades urban life, but because it’s terrible for the homeless.

But while the executive order promises to end the chaos, it fails to address the causes.

Most homelessness is invisible. It’s families sleeping in cars, couch-surfing teenagers, single moms cycling through shelters. They’ve lost housing due to eviction, domestic violence, job loss, illness. These people make up the majority of the homeless population nationally—but because they pass through the system relatively quickly, they remain unseen. The chronically unsheltered, by contrast, dominate the discourse precisely because they are visible.

People want the homeless to be invisible, but it takes more than brute force to make a complex social problem go away.2

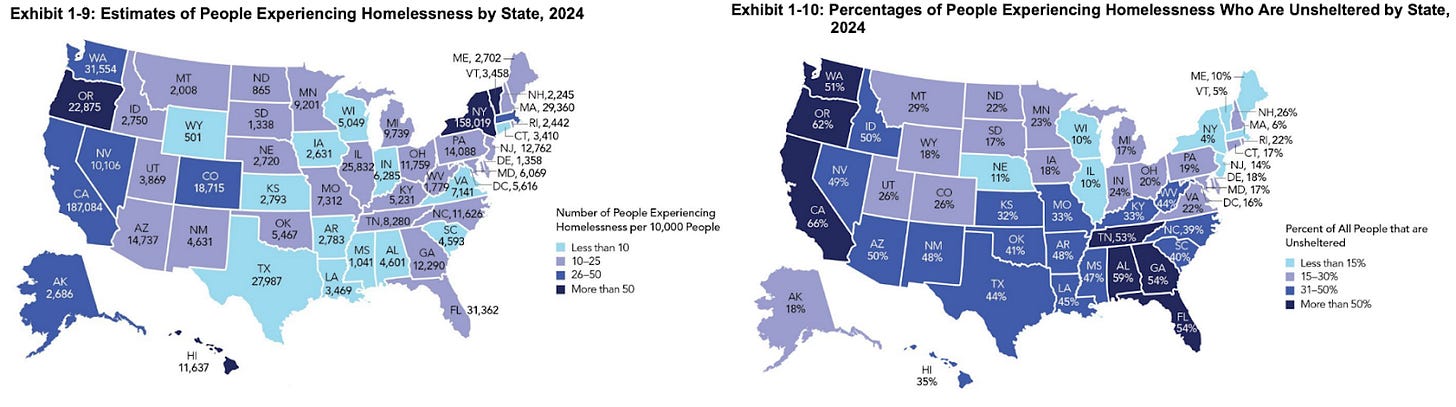

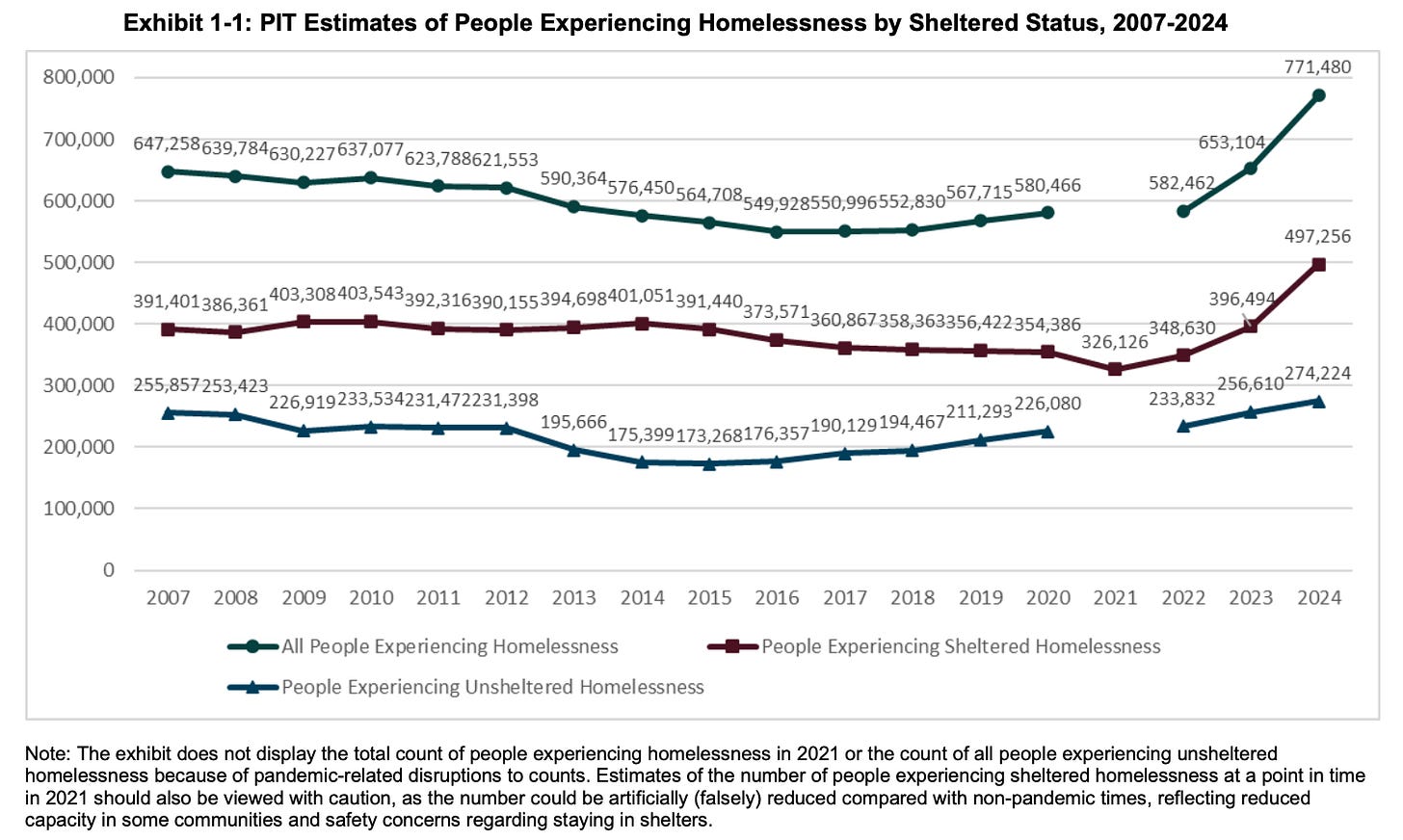

According to HUD, homelessness reached a record high in 2024: 771,480 people on a single night, up 18% from the year before. It’s not just an urban problem—40% live in suburbs—but it’s far more visible in cities, especially those where housing is scarce and expensive. California and New York together account for 45% of total homelessness in America, but they couldn’t be more different. New York shelters over 90% of its homeless, while California shelters just a third—and has nearly half of the nation’s unsheltered homeless population. California’s homelessness rate is lower than New York’s, but its failure to create shelter and affordable housing has made it vastly more visible.

It’s tempting to assume that visible homelessness is caused by addiction or mental illness. Sometimes it is. But often, the causality runs the other way. Street life is profoundly destabilizing. If you lose your home, where do you eat, sleep, shit, shower, charge your phone? Try holding a job without basic hygiene and clean clothes. Try navigating shelter systems without an address or access to healthcare. See how quickly your life falls apart. The longer someone remains unsheltered, the likelier they are to suffer trauma, worsen mental illness, or turn to drugs to cope. The longer you’re on the street, the harder it becomes to leave. Eventually, the crisis becomes your condition.3

Homelessness doesn’t just reflect dysfunction. It generates it.

Nearly 153,000 people were chronically homeless in 2024—and 65% of them were unsheltered. It is this population—about 20% of the entire homeless population—that receives most of the political attention.4

The executive order claims that “the overwhelming majority” of unsheltered homeless individuals are addicted to drugs, suffer from mental illness, or both. The reality is murkier. Most unsheltered people do not currently suffer from both, and many suffer from neither, but reliable numbers are hard to come by. The Housing Rights Initiative estimates that fewer than one-third have a serious mental illness, and 20–40% have substance use disorders. A UCLA study found that 51% of unsheltered individuals cited substance use and 46% cited physical illness as factors in their housing loss—substantially higher than sheltered populations.

Even if the administration were right about the prevalence of illness and addiction, its conclusion doesn’t necessarily follow. Yes, mental illness and addiction are real, but they’re worsened or created by a failure to get people off the streets. Houston has shown an alternative path forward—even for people with serious mental illness or addiction—one that doesn’t require rounding up the homeless but housing them, instead.

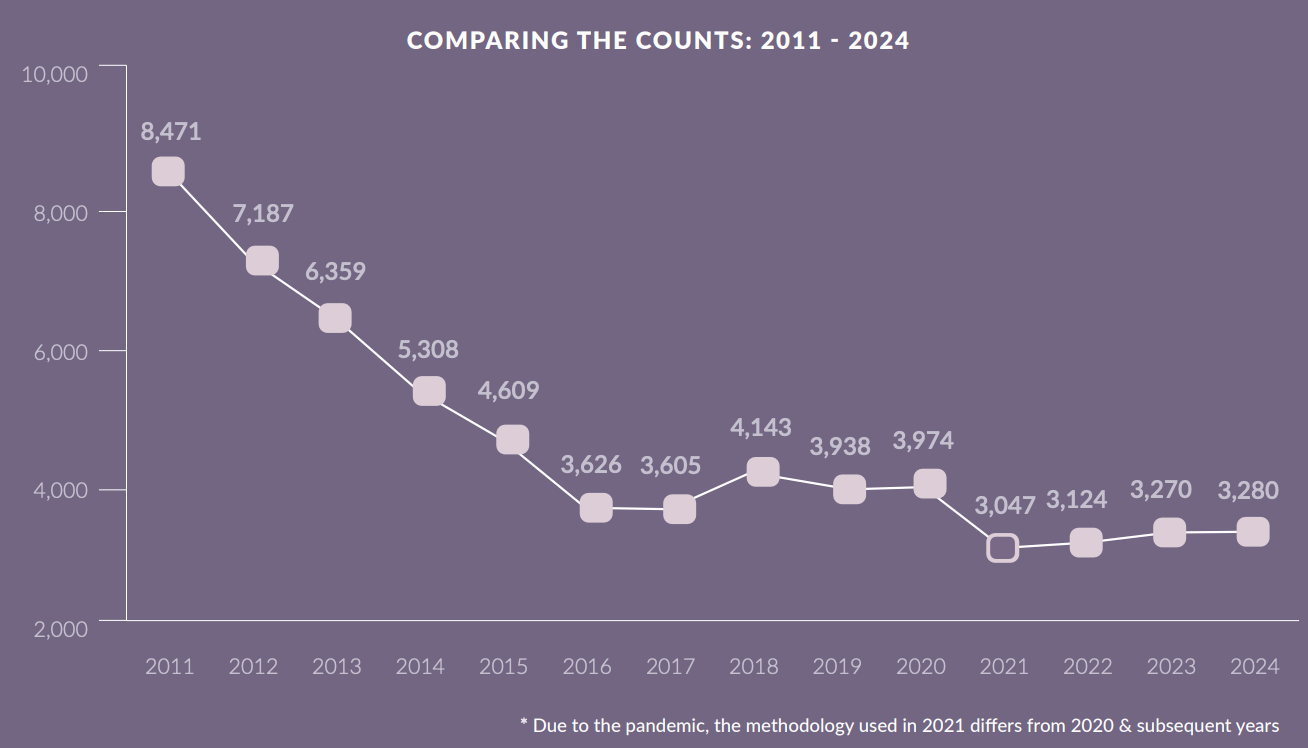

Since 2011, Houston has reduced overall and chronic homelessness by more than 60%. Through The Way Home, a coordinated effort spanning more than 100 public and private agencies, Houston has housed more than 32,000 formerly homeless people—with a 90% success rate.

How did they do it? By shifting from shelters and transitional housing to permanent housing with supportive services. Instead of building new units, Houston leased existing apartments from landlords, paired them with long-term subsidies and case management, and placed people quickly—without preconditions. This approach keeps capital costs low and ensures operational flexibility, while rapidly getting people off the streets before they downward spiral.

This is what a true Housing First homelessness solution looks like. It also helps that Houston has no zoning and low minimum lot sizes, which has made housing there broadly affordable—the best prevention tool. But policy and coordination have made the difference.

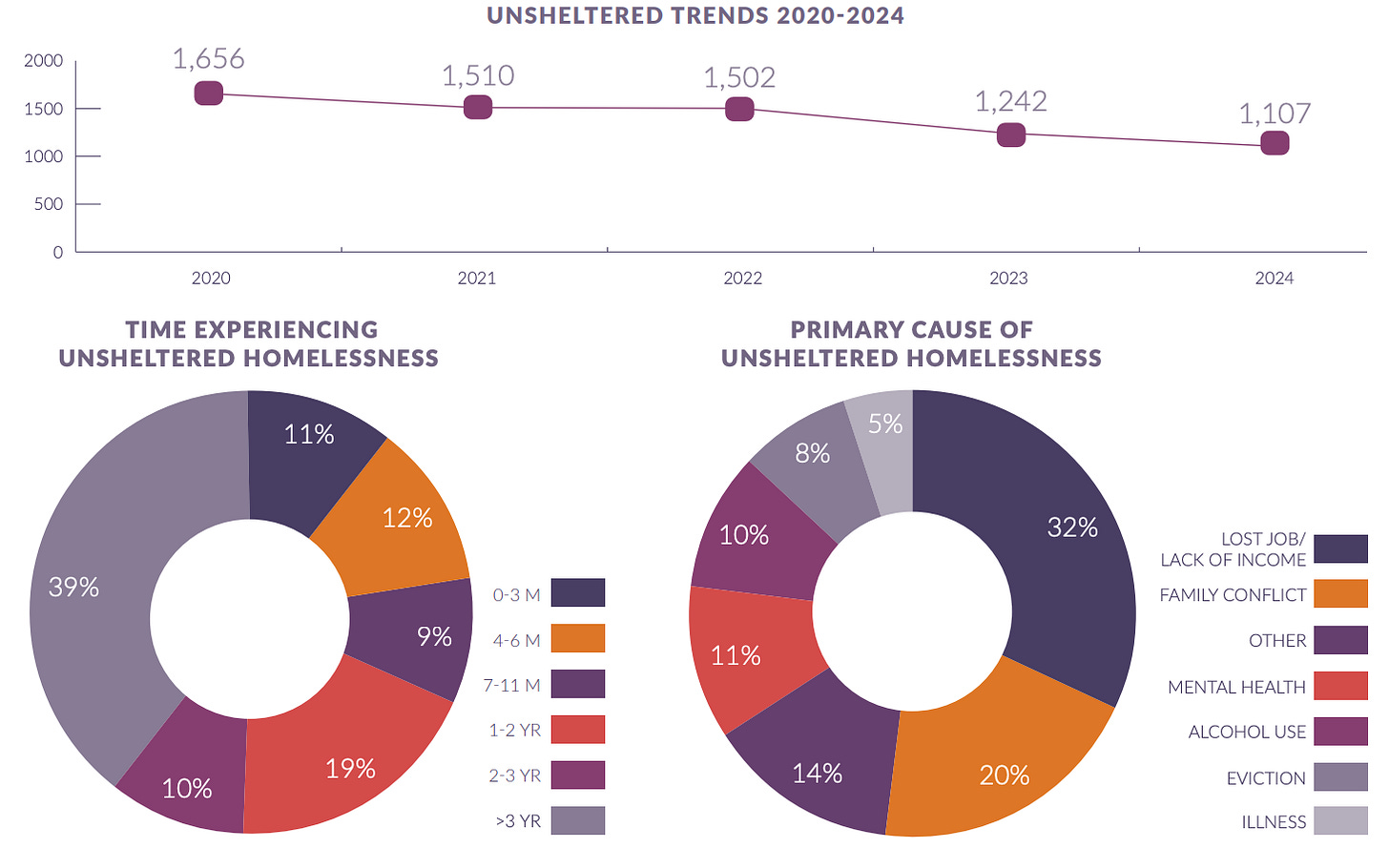

Still, Houston hasn’t reached utopia. About 3,300 people remain homeless, with 1,100 unsheltered. The city hasn’t achieved “functional zero,” where inflow matches outflow and homelessness is brief. But it’s reduced unsheltered homelessness by roughly one-third since 2020, even as overall counts have stabilized.

This matters, because it means that Houston is successfully housing people with mental illness, addiction, and other ailments—without using force. It proves that persistent homelessness isn’t inevitable but the result of choices. Other cities should be studying the Houston model closely.

Contrast this with New York City, where tens of thousands of people remain stuck in shelters for months or years, and “affordable” housing is accessible only by lottery. Or San Francisco, which spends three-quarters of a billion dollars a year “solving” homelessness—yet has seen it grow by 47% since 2011. Or Austin, where homelessness has more than doubled since 2019 and the city has poured millions into shelter expansion and permanent supportive housing—while prevention and rapid rehousing have received less attention and funding.

Both San Francisco and Austin claim to use Housing First, but neither has adopted Houston’s coordinated, data-driven model. San Francisco’s homelessness funding has been wildly—perhaps fraudulently—mismanaged. Austin has meanwhile fixated on slow, high-cost solutions rather than immediate placements—a missed opportunity in a city where rents have fallen steeply. In both cities, chronic unsheltered homelessness remains stubbornly high. Neither system is working, but neither system is actually doing Housing First.

While Houston’s model shows that a true Housing First model can work for the vast majority of the homeless, those who are suffering from deep mental illness and drug addiction need alternative care in treatment facilities. We should remove barriers to and invest in such facilities for that 10% who cannot be served by Housing First. Some might argue that the administration’s executive order simply fills in the last piece of the puzzle—removing the most difficult individuals from the street—but the order suggests such people would be better served in county jails than in treatment centers. That would be an equally costly and far less humane way to make disorder disappear.

Maybe it would make those of us citydwellers “experiencing” the homelessness crisis feel better, but it would do nothing to solve the underlying drivers of the problem.

A few years ago, here in Austin, public frustration led voters to recriminalize public camping, a policy ratified last year by the Supreme Court’s Grants Pass decision, allowing cities to ban public camping even without shelter alternatives. Yet in the absence of necessary interventions—adequate affordable housing and treatment facilities for those suffering from addiction or mental illness—banning camping hasn’t reduced homelessness. Critics claim that it's an enforcement problem, but the reality is that clearing encampments merely relocates homeless people elsewhere in town. It’s a perpetual game of whack-a-mole, not an enduring solution.

Law-abiding, tax-paying citizens should not have to put up with persistent disorder in public spaces—but it’s the persistence of failed policies around housing and homelessness that are preventing the problem from simply going away. Cities that say “not in my backyard” to new housing and proven strategies are effectively saying “yes” to homelessness and disorder on their streets. Visible homelessness will not be solved with policies that make it merely invisible—what’s required is vision.

Cities need only look to Houston to see what works.

“Housing First” prioritizes permanent housing without preconditions like sobriety or treatment, which has been shown to significantly reduce homelessness. Harm reduction—needle exchanges, supervised consumption—reduces overdose risk and disease transmission, but often fails to help people stop using.

In a constitutional republic, at least.

A review of the literature finds that unsheltered homelessness exacerbates mental illness, addiction, and physical illness: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10546518/

HUD defines chronic homelessness as lasting at least 12 months continuously—or over four episodes in three years—for individuals with a disability.

This is a refreshing take on the issue and speaks to the gap between what many NIMBY liberals claim to want and what they really want. This reminds me of when I lived in Calgary years ago and they opened a supervised (drug) consumption center in the middle of the city. People went there to use with clean needles and in a safe environment. This often exposed them to opportunities to find treatment, reduced both overall usage rates, and the prevalence of people using on the streets. The NIMBY's bemoaned the inevitable skyrocketing of crime that would come with it...and it never materialized. I applaud you for supporting a position that actually intends to do something about the issue without letting perfect be the executioner of good options.

I also believe that family estrangement, and many families relocating due to jobs, or various other reasons, has left some people without any support system. I enjoyed the article and responses