The Banished Bottom of the Housing Market

How America Destroyed Its Cheapest Homes

Today, a young man down on his luck in a new city is more likely to land in jail or on the street than on his feet. Fifty years ago, he had another option. A place to wash up, get a hot meal, meet other young men—even start over. All he had to do was put his pride on the shelf and get himself to—well, you can spell it out: the YMCA.

The Village People’s 1978 disco hit celebrated one of the less-remembered services offered by the YMCA. From the 1860s, the YMCA began building single-room occupancy (SRO) units “to give young men moving from rural areas safe and affordable lodging in the city.” At its peak in 1940, the YMCA had more than 100,000 rooms—“more than any hotel chain at the time.” The Y wasn’t the only provider of such housing; indeed, there was a vibrant market for hotel living that existed well into the twentieth century.

Variously and derogatively known by many names—rooming houses, lodging houses, flophouses—SROs provided affordable, market-rate housing to those at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder. SROs were the cheapest form of residential hotels, specializing in furnished single rooms for individuals, usually with shared kitchens and bathrooms. A typical SRO rent in 1924 was $230 per month—in today’s dollars.1

As late as 1990, as many as two million people lived in residential hotels—more than lived “in all of America’s public housing”—according to Paul Groth, author of Living Downtown.2 Today, not so much. SROs like those offered by the YMCA were the safety net that kept many people off the streets—and their disappearance from the housing supply explains much of modern-day homelessness. What we destroyed wasn’t just a housing type but an entire urban ecosystem: one that provided flexibility, independence, and affordability at scale.

As with so much of our urban history, this destruction was by design.

From the mid-1800s to the early 1900s, hotel living was a normal way of life for people of all socioeconomic backgrounds. As hotelkeeper Simeon Ford colorfully put it in 1903, “We have fine hotels for fine people, good hotels for good people, plain hotels for plain people, and some bum hotels for bums.” SROs, the “bum hotels,” were the backbone of affordable housing, serving “a great army” of low-paid but skilled workers. Clustered in lively downtown districts with restaurants and services that acted as extensions of the home, SROs offered liberation from family supervision and the constraints of Victorian mores. Rooming house districts let young people mix freely and even allowed same-sex couples to live discreetly—signs of a more secular, modern urban culture. Downtown hotel life, Groth notes, “had the promise to be not just urban but urbane.”

And therein lay the problem: the urbanity of SROs collided head-on with the moralism of the Progressive Era.

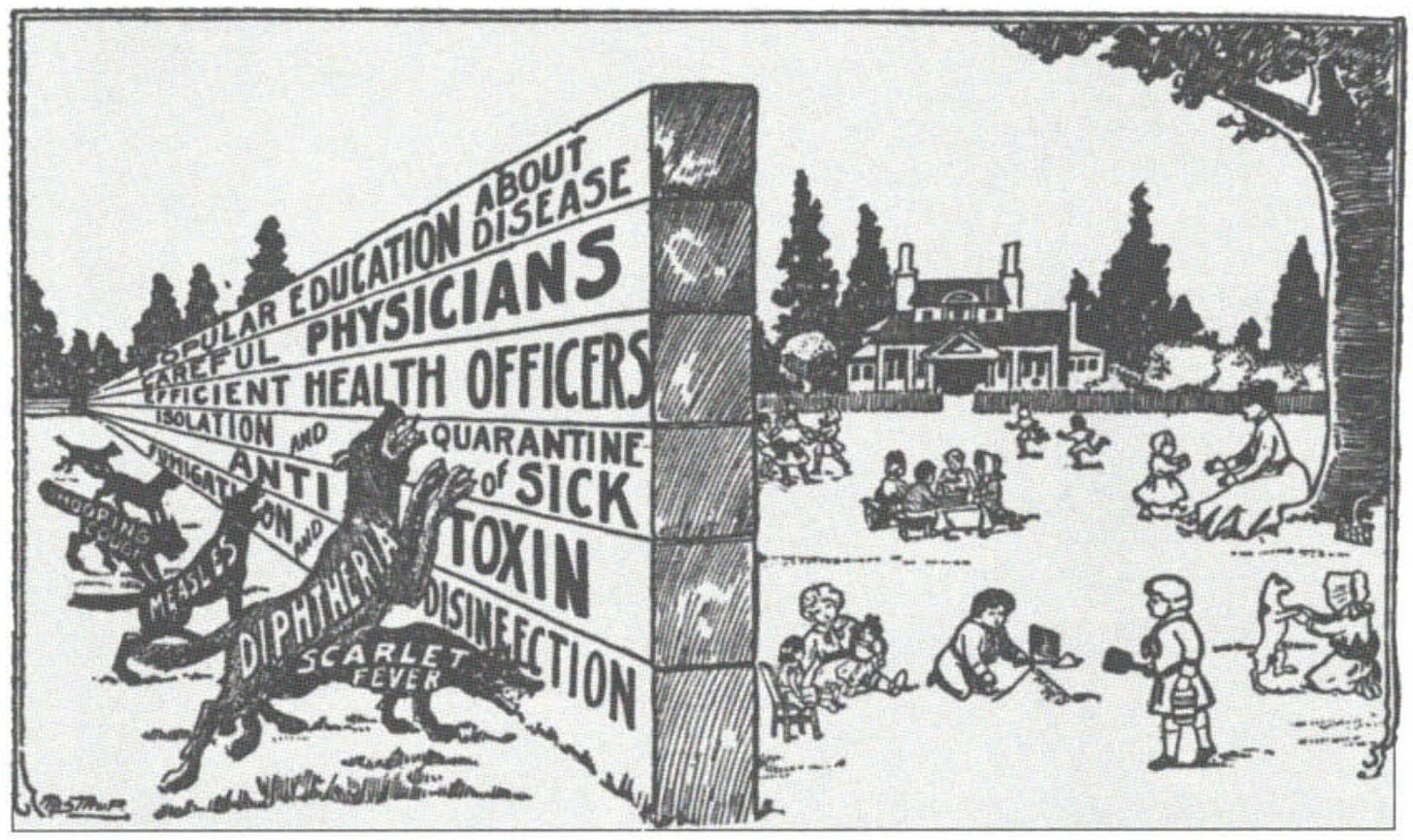

Reformers drew on a long tradition of anti-urban bias, seeing the emergent twentieth-century city as a problem, with cheap hotels at its heart. They pathologized hotel dwellers as “friendless, isolated, needy, and disabled” and cast SROs as “caldrons of social and cultural evil.” Some of the cheapest hotels were unsafe and exploitative, but reformers cared less about improving conditions than about what the hotels symbolized. They blamed rooming houses for loneliness, sexual licentiousness, civic apathy—even suicide. To them, the presence of “social misfits” proved that hotels caused moral disorder. In reality, people lived in SROs because they were cheap and offered greater independence—especially for career-oriented young women. Firm in their belief in the “One Best Way to live,” the reformers exalted the single-family home as the “bulwark of good citizenship” and succeeded in stigmatizing hotel life.

By the turn of the century, they set their sights on changing the law.

Beginning in the late 19th century, reformers used building and health codes to erase what they saw as “aberrant social lives.” San Francisco’s early building ordinances targeted Chinese lodging houses, while later codes outlawed cheap wooden hotels altogether. By the early 1900s, cities and states were classifying lodging houses as public nuisances. Other laws increased building standards and mandated plumbing fixtures, raising costs and slowing new construction. Urban reformers next embraced exclusionary zoning to separate undesirable people and noxious uses from residential areas. SROs were deemed inappropriate in residential zones, and many codes banned the mixed-use districts that sustained them. In cities like San Francisco, zoning was used to erect a “cordon sanitaire” around the prewar city “to keep old city ideas from contaminating the new.”

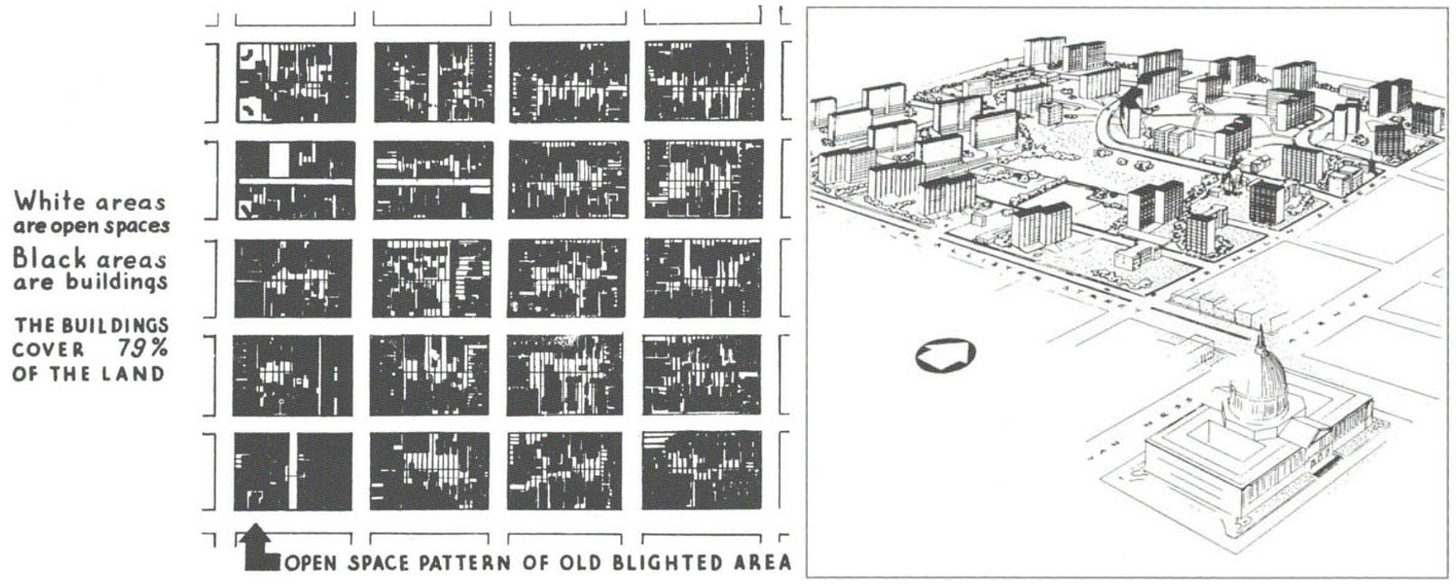

Residential hotels, like apartments, were swept into the same category of “mere parasitic” uses that Euclid v. Ambler—the 1926 case that upheld zoning—treated as potential health hazards. Redlining and federal loan criteria starved urban hotels of capital, while planners simply omitted them from surveys and censuses—as if their residents didn’t exist. By the urban renewal era, the existence of the old city was itself seen as an affront, and it, too, had to be destroyed.

In effect, SROs became a “deliberate casualty” of the new city.

Economic and policy shifts hastened their decline. Industrial jobs moved to peripheral locations only accessible by car, urban highway expansion targeted lodging-house neighborhoods, and cities encouraged office development on increasingly valuable downtown land. The “moral blight” of hotel districts had increasingly become economic blight, necessitating renewal. And because SROs didn’t count as “permanent housing” in official statistics, clearance programs could claim to displace no one. San Francisco’s urban renewal experience was typical: redevelopment in and around the Yerba Buena/Moscone Center area ultimately eliminated an estimated 40,000 hotel rooms. The public housing that replaced hotel districts—if it was built at all—often failed to accommodate single adults. To bureaucrats, the bulldozer was salubrious, “eliminating dead tissue” and “clearing away the mistakes of the past.” To the people who lived there, it wiped out their last foothold in the housing market.

By the mid-twentieth century, “millions” of SRO hotel rooms disappeared through closures, conversions, and demolition across major cities, and the modest hotel market that remained was shrinking fast. With almost no new SROs built since the 1930s, the remaining stock was vanishing by the thousands in the 1970s. New York City had 200,000 SROs when it banned new hotel construction in 1955; only 30,000 remained by 2014. As tenants changed and land values climbed, owners who once fought to save their lodging houses now wanted out; it was officials who suddenly wanted to preserve them. Tenant movements and new government programs emerged in the 1970s and ’80s, but Reagan-era cuts gutted funding, and many remaining hotels decayed into the “street hotels” opponents had long imagined: unsanitary, unsafe, and unfit for all but the city’s most desperate residents.

At the same time, demand for SRO housing was rising sharply. In the 1970s, states emptied mental hospitals without funding alternatives, pushing thousands of people with serious needs into cheap downtown hotels unequipped to support them. What was left of the SRO system became America’s accidental asylum network—the last rung of shelter for those the state had abandoned.

Thousands of people were barely hanging on, and a full-blown homelessness crisis had emerged in American cities for the first time since the Great Depression.

The SRO crisis was no accident, Groth argues, but the result of government policy at all levels that picked winners and losers in the housing market. The people we now call “chronically homeless” were once simply low-income tenants, housed by the private market in cheap rooms rather than by public programs. Once that market was dismantled, the result was predictable: the homelessness wave of the late 1970s and 1980s followed directly from the destruction of SROs. Today’s crisis—nearly 800,000 unhoused people in 2024—is the long tail of that loss, compounded by decades of underbuilding in expensive cities and soaring rents. As one advocate put it, “The people you see sleeping under bridges used to be valued members of the housing market. They aren’t anymore.”

As Alex Horowitz of The Pew Charitable Trusts writes, if SROs had “grown since 1960 at about the same rate as the rest of the U.S. housing stock, the nation would have roughly 2.5 million more such units”—more than three times the number of homeless individuals. While we can’t rebuild the old SRO market we destroyed, cities now face a new opportunity: a vast surplus of obsolete office space that could be converted into inexpensive rooms.

Horowitz argues cities should make shared housing—“co-living,” in today’s parlance—legal again. Office vacancies are soaring at the same time deeply affordable housing is vanishing. Horowitz and the architecture firm Gensler modeled what cities could actually build. Their analysis suggests that a vacant office tower could be converted into deeply affordable rooms for half the per-unit cost of new studio apartments. A typical 120–220 square foot unit with shared kitchens and bathrooms could rent to people earning 30–50% of area median income. Urban development has become so expensive that such conversions are likely to only be feasible if subsidized, but Horowitz argues that conversions offer a better way to leverage scarce public dollars: for instance, a $10 million budget might produce 125 co-living rooms instead of 35 studios, providing a way to scale deeply affordable housing much more quickly.

It’s a great idea—but in many cities, it’s illegal.

While several cities have made efforts to undo SRO prohibitions, in many American metropolises, restrictions abound—from zoning that bans shared housing or residential uses in office districts to minimum-unit-size rules that outlaw SRO-scale rooms. Building codes with strict egress and corridor rules and ventilation requirements make conversions technically infeasible, while parking mandates add unnecessary costs. Meanwhile, “unrelated occupancy” limits prohibit the very household types SROs serve.

None of these barriers is structural; every one is a policy choice.

We talk endlessly about the “missing middle.” But the real catastrophe was the “banished bottom”—the deliberate destruction of the cheapest rung of the housing ladder. Re-legalizing SROs won’t instantly restore a once deeply affordable housing market that provided housing at scale, but it would at least make it possible for cities to create a much cheaper form of housing that could benefit some of the 11 million extremely low-income renter households and the 800,000 homeless people in America. No city will meaningfully address the need for deeply affordable housing until it restores this missing rung—and accepts that not everyone needs a full apartment to have a full life. Surely, an SRO is better than a sidewalk.

Incidentally, while the YMCA is generally not in the SRO business anymore, its Austin branch is redeveloping itself as a mixed-use center with 90 deeply discounted affordable units for families. It’s a worthy project—but it highlights the gap: more than 80% of Austin’s homeless residents are single adults, the very group the Y once housed. We used to have a place they could go—but what happened to that?

The Y is as much a question as an answer.

Quotations pulled from Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels in the United States by Paul Groth.

Great article. While I can’t imagine running a SRO- a task for a staff with case managers, on another level, allowing good new fashioned boardinghouses to function properly is another way to allow for single rooms in a large house to be occupied in any number of configurations to shelter more people.

In a boarding house it is up to the resident owner, or manager to create a set of house rules for the co-tenants to live in a place of mutual respect and well-being. That “head of the household” has a responsibility to fairly manage and adjudicate this co-living space and warn and evict when merited a person for unacceptable behavior. Careful screening, and a compassionate, flexible perspective will foster peace and stability for all residents.

The problem is that there is only one set of just cause eviction control rules that cover all rental situations. This effort to create housing stability has the effect of drastically limiting the ability for the person responsible to manage such a rooming house when it comes time to move someone along that is incompatible.

Laws such as this, and an impacted court system are a poor solution to resolve the complexities of people living together. We need to reexamine, experiment, allow for innovation in providing housing, especially to an already stressed population.

Powerfully written, thank you Ryan. SROs weren’t just sources of housing stability, they were basically the first rung in the latter of economic mobility. We as housers have some work to do sharing the history about just how low the cost of housing at the bottom of the market can be. It’s hard for most to imagine that outside major recessions the U.S. had very little homelessness in the past, even though we spent way less tax money subsidizing housing

I like Alain Bertaud’s justification in Order Without Design for allowing really low quality housing to exist: People know their own consumption preferences best, and they should be free to save money by living in low cost housing so they can choose to spend it on other things they find more valuable